WSU’s Hike of Hikes Turns 100

Karin Hurst AS ’79, Marketing & Communications

Among the items you’d least expect to see displayed in President Brad Mortensen’s conference room is a 100-year-old hunk of oxidized steel. Yet, there it lurks — a jagged-edged, 24-inch cylinder bathed in a rich palette of rust, silver and charcoal — unabashedly greeting visiting donors and

dignitaries, and silently presiding over official gatherings of administrators, faculty, staff and community leaders. Those unfamiliar with Weber’s past would not likely guess the corroded curiosity is a precious relic of a venerable school tradition. But it is.

dignitaries, and silently presiding over official gatherings of administrators, faculty, staff and community leaders. Those unfamiliar with Weber’s past would not likely guess the corroded curiosity is a precious relic of a venerable school tradition. But it is.

A Change in the Air

Weber College was undergoing a pivotal transition in the autumn of 1922. At the end of that school year, high school classes would no longer be offered. For President Aaron Tracy, Weber’s imminent adoption of college-only academic curricula was the fulfillment of a dream. College student body president J. Willard Marriott and high school student body president Llewelyn McKay teamed with sociology faculty Harvey L. Taylor to plan a fitting celebration. They settled on the audacious idea of leading a march to the 9,579-foot summit of Mount Ogden to “crown the peak” with a steel flagpole. In its Oct. 3, 1922, edition, the Weber Herald student newspaper, urged all 630 students enrolled to participate in the Oct. 4 event and sign sheets of paper that would be placed in a glass jar and encased at the foot of the flagpole “as a sign that you love your school and share in her gift to those that are to follow.”

WSU professor emeritus Gary D. Willden, aka “Dr. Fun,” taught outdoor adventure and recreation for 35 years and understands the appeal of blisterbursting, muscle-cramping hikes. “It’s in some ways almost a spiritual experience,” he said. “The sights and sounds and sensations in places like that, you just don’t find in valleys.”

According to Willden, marking an important milestone with a large group trekking to a single destination wasn’t uncommon in an era that pre-dated TV and social media. Large groups of Utah hikers had been scaling the 12,000-foot summit of Mount Timpanogos together yearly since the summer of 1912. What amazes Willden about Weber’s inaugural Mount Ogden Hike is the ruggedness of the original route, the large turnout (an estimated 350 to 365 participants) and the fact that their mission was accomplished in one day.

“Snowbasin was not developed in 1922, so the original hikers came up the Taylor Canyon side,” he explained. “From that side, you’ve got a nice trail up to Malan’s Basin, where there are remnants of Malan Heights, a Gilded Age hotel and resort. But once you get out of there, it’s pretty much bushwhacking and boulder hopping the rest of the way up to the saddle.”

An Explosive Start

Technically, the original trekkers had some assistance, courtesy of a six-member vanguard crew that traveled to Mount Ogden Peak by horseback on Saturday, Sept. 30, to forge a rudimentary trail and sledgehammer a hole deep enough to bury a charge of dynamite. The explosion created a three-foot crater to accommodate the base of the flagpole.

Between 4 and 5 a.m. on Wednesday, Oct. 4, a noisy swarm of students, faculty and trustees gathered near a rock landmark at the mouth of Taylor Canyon. The students split into groups according to age, each charged with a specific task. The high school sophomores would carry water, sand and cement; juniors would haul the 300-pound steel flagpole in three sections. (A team of six horses was brought in to carry the heavy load, but as the trail grew steeper and more treacherous, the students had to transport the pole sections themselves.) Once they reached the peak, seniors would set the pole; student body leaders would splice the pole pieces; and college students would raise the United States and school flags.

The hikers began their ascent as the school band cheered them on with lively tunes. Faculty led the way, followed by high school sophomores, junior and seniors, with college students bringing up the rear.

Nine grueling hours later, the weary masses reached their destination. They paused long enough to eat lunch before raising the flagpole to its 20-foot height, placing it into the prepared hole and packing it tightly with concrete mixed on the spot.

An inscription on a bronze plaque bolted to the bottom of the flagpole read, “Presented by the Associated Students of Weber College, 1922.”

Admiring what they considered their gift to future generations, the hikers listened attentively to remarks from President Tracy and student leaders. Llewelyn McKay’s father, Weber College Board of Trustees president, alum and former principal, David O. McKay, complimented the students on their miraculous feat, reminding them that “all things worthwhile in life are difficult of attainment, just as the reaching of the peak had been.” McKay, a Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints apostle, then offered a dedicatory prayer. Accompanied by the wail of a bugle, college students hoisted the two flags. The program concluded with the group singing the “Star-Spangled Banner” and “Purple and White,” Weber’s newly composed school song.

For the next decade, the trail through Taylor Canyon, past Malan Heights and up to the summit of Mount Ogden was known as the Weber Trail. However, by 1932, an alternative campus tradition had emerged. It involved a much easier hike to Malan’s Peak and culminated in the lighting of a large bonfire after which participants hiked back down the trail in moonlight. This activity became known as the Flaming W Hike.

What Went Up Must Come Down

Clearly, the intent of those who erected the steel structure on Mount Ogden’s windy peak in 1922 was for it to last forever. So, you can imagine alum Ted McGregor’s angst close to five decades later when he burst into then alumni association director Dean W. Hurst’s office claiming the U.S. Forest Service had enforced a law mandating the removal of all unauthorized structures on northern Utah mountains, including Mount Ogden. (McGregor was among the vanguard unit that created a hole for the pole’s foundation.)

To confirm the rumored demolition, McGregor and Hurst flew over the peak in a private plane. They saw that the flagpole had, indeed, been knocked down in sections and hurled over the eastern cliffs. Hurst said he visited the site a short time later in hopes of finding the Mason jar that contained the signatures of the hike participants, but only managed to recover a piece of concrete that appeared to bear the impression of a glass jar lid, and a rusty, two-foot fragment of flagpole. While the current whereabouts of the concrete remains a mystery, the chunk of pole was disinterred from a long-forgotten storage box in the basement of Lindquist Alumni Center shortly before Mortensen’s 2020 inauguration. He has displayed it as a symbol of school pride and student tenacity ever since.

“In their official government language, the Forest Service referred to the flagpole as ‘an unauthorized protuberance,’ so they tore that out,” Willden lamented. “Well, in the years since then, all kinds of ‘protuberances’ have been authorized and the place now looks like an airport!” In 1975, the Forest Service granted alumni leaders permission to secure a bronze memorial plaque to an outcropping of rocks on the peak, but an early mountain snowstorm delayed that effort until August of 1976.

Reviving a Rugged Adventure

In 1987, then Weber State president, Stephen Nadauld, asked Willden to revive the legendary hike. Despite atrocious weather and a meager turnout, the activity generated enough enthusiasm that Nadauld promoted the following year’s hike as part of the college’s 1988 centennial celebration.

“He came up with some private funding to pay for a helicopter and we were able to locate four elderly gentlemen who had made the inaugural hike and transport them up to the saddle to greet the roughly 300 hikers,” Willden reminisced. “It was beautiful weather. There were some folding chairs and a PA system so we could have a nice program.”

Celebrating a Century

On Oct. 4, 2022, the Mount Ogden Hike turned 100. WSU Campus Recreation associate director Daniel Turner and a 15-member committee spent nearly two years planning a commemoration that was bigger and more elaborate than anything ever done.

“We tried to make 2022’s hike as similar as possible to the 1922 hike,” Turner said. “We continued the tradition of carrying the Weber State flag with us, but by using the Snowbasin route instead Taylor Canyon, we were better able to manage the risk associated with hiking that mountain with a large group of people.”

The event, held Sept. 24, 2022, began at Earl’s Lodge patio with a light breakfast, a greeting from President Mortensen and the introduction of special guests, including 95-year-old Quinn G. McKay, a David O. McKay family representative. The marching band provided a rousing send off as participants split into advanced, intermediate and beginner hiking groups. Some folks chose to ride the gondola to Snowbasin’s Needles Lodge, which eliminated three quarters of the distance. “One of our key goals was to meet people where they were in terms of age and ability,” Turner explained.

The event, held Sept. 24, 2022, began at Earl’s Lodge patio with a light breakfast, a greeting from President Mortensen and the introduction of special guests, including 95-year-old Quinn G. McKay, a David O. McKay family representative. The marching band provided a rousing send off as participants split into advanced, intermediate and beginner hiking groups. Some folks chose to ride the gondola to Snowbasin’s Needles Lodge, which eliminated three quarters of the distance. “One of our key goals was to meet people where they were in terms of age and ability,” Turner explained.

An afternoon program at the saddle, just below the summit, featured the unveiling of a 100th anniversary plaque. The crowd sang “Purple and White,” as well as the school’s familiar fight song, which has declared Weber State “great, Great, GREAT” since 1965.

A Hike Worth Remembering

In its current iteration as in its past, Weber’s trek to Mount Ogden Peak is more than a pleasure hike. At its core, the Mount Ogden Hike is a metaphor for Weber’s remarkable trajectory from Weber Stake Academy to Weber State University. In 1922–23, as high school courses yielded to junior college curriculum, students and faculty were hopeful, yet largely uncertain about the future of their beloved institution. The community at large also wondered what would happen next. By staking a flagpole at the summit of  Mount Ogden, Weber staked its claim to the past, present and future.

Mount Ogden, Weber staked its claim to the past, present and future.

“Here’s a group of 350 faculty, staff and students that, by establishing that flagpole on that mountain top that day, said, ‘Weber is here to stay,’” Turner said.

As the editors of the Acorn Souvenir yearbook noted so prophetically in their 1922–23 publication: “Ogden City realizes as this school year ends, that Weber College is established to remain and that it has attained that true spirit which will mean growth for the community, for the college, and for the individual.”

Turner said he believes that someone at WSU will always assume the mantle of overseeing an annual hike.

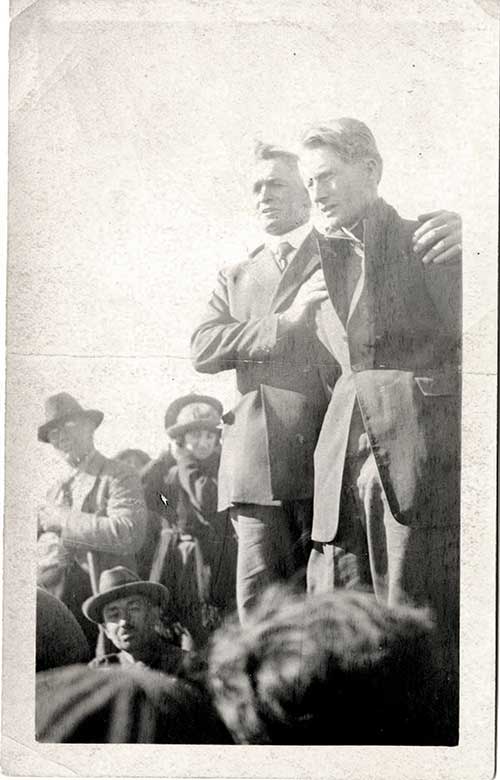

David O. McKay (center) and Weber College president Aaron Tracy (right) speaking to hikers during the 1922 flag ceremony

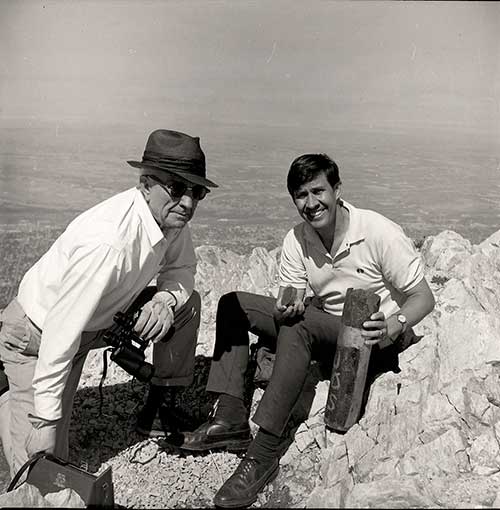

Russell Croft (left) and Dean Hurst (right) on Mount Ogden in 1970 holding the remnants of the 1922 flagpole

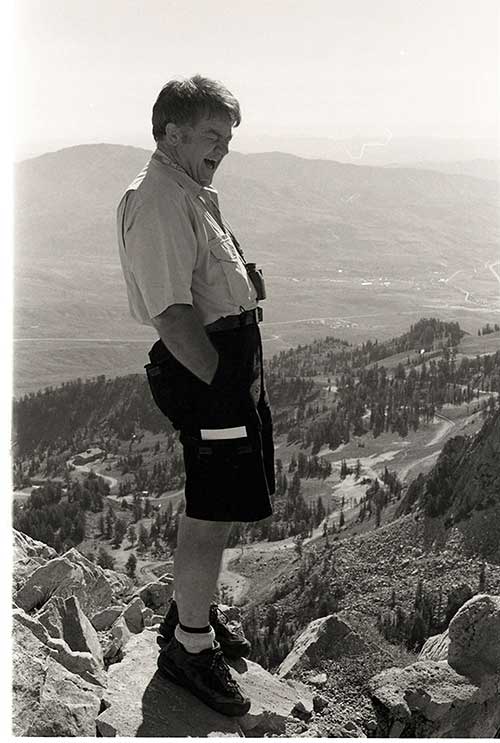

Gary Willden standing at the top of Mount Ogden in 2002

Hikers making their approach to the peak of Mount Ogden in 2022