A Leap of Faith, An Unlikely Liaison

Karin Hurst MARKETING & COMMUNICATIONS

Does this sound familiar? While skimming through Facebook messages, you stumble on one that trips an internal alarm — a cryptic plea from someone you’ve never met, in a country you’ve barely heard of.

Helo Sir, wel my name is Joel from Liberia, West Africa. Pls I beg u in name of GOD, I need some assistance from u, business or financial assistance dat will help empower me pls.

Your eyes narrow. Your indignation flares. With a violent jerk, you click “delete” ... unless you’re WSU alumnus and adjunct instructor of communication Ben Taylor BS ’09, MPC ’15, who writes back, “Hey, Joel. How can I help?”

Taylor didn’t believe for one second that “Joel from Liberia” was “legit.” He just wanted to string the diabolical cyber-shyster along for as long as possible to keep him from fleecing other, more naïve, internet users. Taylor had good reason to be frustrated. Every year, clever con artists combine new technology with old tricks to rip people off. A FederalTrade Commission report shows that 2.68 million consumers filed fraud complaints totaling $905 million in losses in 2017.

Joel asked Taylor to send laptops, computers, printers and other electronic devices to a contact in New Jersey who would pack the items into barrels and ship them to Liberia. Taylor didn’t take the bait. Instead, he hatched his own scheme. Claiming to work in the photography industry, Taylor told Joel to send pictures. He promised to pay for any he found interesting.

Interesting isn’t the right word to describe what Joel sent. The bizarre collection of blurred images may or may not have been Liberian landscapes. Still, Taylor had to give Joel credit for trying. Convinced the source of Joel's questionable photography was an archaic cell phone lens, Taylor purchased a low-end, point-and-shoot Vivitar and put it in the mail. Miraculously, the camera made it to Joel s village near Monrovia, where the eager recipient launched a picture-taking frenzy. Still, the quality of Joel s photos didn’t improve.So, in marathon email exchanges, during which Taylor’s wife, Jessica, simply shook her head, the two newbie business partners talked shop. They discussed lighting, framing, composition and how to find interesting subjects. Taylor fully expected Joel to give up. To his surprise, Joel kept practicing, until slowly — over several weeks — the photos began to improve. Taylor was genuinely impressed.

Now, Taylor faced a conundrum. He had “hired” Joel to take good photographs and Joel had honored the agreement. If Taylor didn't follow through with a paycheck, he'd be the scammer, not Joel. Followers of Taylor’s YouTube channel urged him to keep his word.

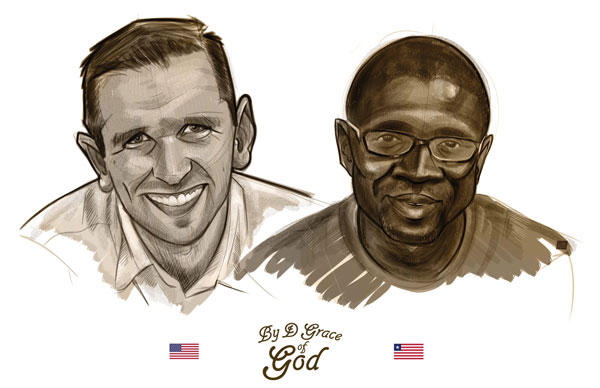

So, Taylor took 11 of Joel’s best shots, created a booklet titled By D Grace of God (Joel’s catchphrase) and marketed the publication through Indiegogo, a global crowdfunding platform. To his astonishment, sales took off. People all over the world started buying Joel’s book. The project raised $13,000, but cleared only $1,000 because Taylor had neglected to factor in the exorbitant price of international shipping.

Scammer Or Saint

Next came Joel’s moment of truth. As equal partners, Taylor and Joel were to split the profits 50-50, but Taylor decided to put Joel’s integrity to the test. He wired Joel the total amount with a request that half be donated to a Liberian charity. He thought he’d never hear from Joel again. But a couple of days later, Joel sent snapshots of beaming Liberian children sporting new backpacks. He had rented a taxi, driven to the marketplace, bought every backpack and school supply he could get his hands on, and delivered them to five local schools. In one unpredictably heroic act, Joel, the would-be scammer, went, in his own words, “from zero to hero.”

When Taylor’s YouTube viewers started urging him to fly to Liberia to meet Joel face to face, and even sent money for him to do so, the story caught the attention of CBS News correspondent Steve Hartman, who called Taylor and asked if he and a camera crew could tag along.

Hartman’s heartwarming tale of a shady solicitation that morphed into a bona fide business aired March 30, 2018, on CBS Sunday Morning, an award-winning television news program with an estimated 5.89 million weekly viewers. Hartman concluded the segment with a provocative observation: “Just because a person is poor doesn’t mean they’re not rich in character. In fact, many are great humanitarians, just waiting on the means.”

And while that may have signaled the end of the story as far as CBS News was concerned, Taylor’s saga was far from over; in fact, he’s still writing the next chapter.

Too Much Too Soon

The CBS Sunday Morning piece triggered an avalanche of international interest in bydgraceofgod.com. “We made $60,000 that day,” Taylor told Weber State students, faculty and guests attending a fall 2018 John B. Goddard School of Business & Economics Ralph Nye Lecture. The booming enterprise put Taylor in an even greater position to provide economic aid to Liberia. But with time, came perspective. When Taylor learned that the average Liberian wage earner makes between $456-$1,140 U.S. dollars a year, he began having second thoughts about giving Joel that lump sum payment of $1,000. “I gave Joel way too much money at the start,” Taylor admits.

“When we walked in with our news cameras and he was wearing new shoes, a new watch and had a new roof on his house, his neighbors got jealous. It created a lot of animosity, and he eventually had to move to a new area.”

Brady Presidential Distinguished Professor of Economics John Mukum Mbaku, a Brookings Institution Nonresident Scholar and attorney, maintains that trying to help one person at a time in a developing nation can backfire. “Individual donors and nongovernment agencies can’t help everybody; they can only help certain people who will then move into a different social class,” Mbaku explains. “Even if you went to a village and gave everybody $1,000, you still create a jealousy problem. If you’re a father and you get $1,000, you have to take care of your family, but if you’re a 10-year-old kid and you get $1,000, it’s all for you.” Mbaku, a former associate editor of the Journal of Third World Studies and a consultant to the U.N. Economic Commission for Africa, says before anyone can help Liberia, they must understand its history.

Repeating Racial Repression

Liberia was founded in 1822 by the American Colonization Society as a haven for freed slaves. Its founder believed that former slaves could never successfully integrate into American society and would only reach their full potential as human beings in Africa,the “land of their fathers.” The organization worked with the United States government over time to transport an estimated 13,000 colonists to a small stretch of West African coastline, later named Monrovia in honor of U.S. President James Monroe. The African-American repatriates called themselves Americo-Liberians.

In 1847, the freed slaves proclaimed their independence — a move that Mbaku says had grave repercussions. As settlers built schools and churches and an economy fueled by agriculture, shipbuilding and foreign trade, the Americo-Liberians expanded their property boundaries deeper into the African hinterlands. Instead of creating a society of independence and opportunity, however, the ex-slaves replicated the cruel plantation culture under which they had suffered.

Dressed in hoop skirts and tailcoats and comfortably housed in lavish mansions reminiscent of antebellum New Orleans, they lorded over the area’s multiple indigenous populations, denying them political and property rights and forcing some into a repressive system of labor tantamount to slavery.

For generations, Liberia’s economy both drove and reflected this larger political narrative. The path to prosperity for a well-to-do Liberian was through connections in Monrovian politics, not through business itself. Most unconnected Liberians were subsistence farmers or petty traders. Foreign investors filled in the gaps by establishing market domination in unprotected sectors. As a result, Liberia’s nondiversified economy was characterized by large foreign natural resource interests, nonresident trading houses, and weak, insulated Liberian firms.

A Nation Unhinged

In the 1960s and 1970s, Monrovia was an opulent playground for the local elite and their foreign friends. But smoldering beneath Liberia’s impressive economy were decades of tension between Americo-Liberians and native populations. The conflict exploded in 1980 when 28-year-old native soldier Samuel Doe and his army stormed the executive mansion, assassinated President William Tolbert, and publicly executed eleven members of his cabinet.

Doe’s leadership was marked by economic devastation and escalating violence. “Samuel Doe promised to establish a system of democracy, but then he acted just like the people he had removed from power,” says Mbaku. “He didn’t come to power through a democratic process; he forced his way through to power by killing people.”

In 1989, rebel warlord Charles Taylor mounted a counter-in- surgency that dragged Liberia into 14 blood-soaked years of intermittent, but ferocious, civil war that left 250,000 people dead and gave rise to rampant reports of cannibal warlords with terrifying monikers, child soldiers pumped up on speed, and the systematic rape, torture, exploitation and mutilation of African women.

In 2003, the United Nations sent 15,000 troops — its largest ever peacekeeping mission — to Liberia to support a cease-fire agreement. In 2014, whatever economic strides had been made were decimated by a deadly Ebola virus epidemic. When the U.N. mandate expired on March 22, 2018, Liberian president George Weah, a retired professional soccer player, toasted the effort at a public celebration. On its website, the U.N. proudly proclaimed that Liberia now has “great potential to achieve lasting stability, democracy and prosperity.”

A Challenge to Change

Mbaku’s prognostication is a bit more skeptical. He believes Liberia hasn’t gone far enough to change what economists call the “institutional structures” that led to the violence. Mbaku says little has been done to tackle Liberia’s cultural tradition of bribery, corrupt leadership and customary laws that discriminate against certain groups, especially women. “What they should have done when the U.N. was there, was establish a system of governance that is based on separation of powers with checks and balances,” Mbaku says. “Most of the indigenous groups are still shut out of the system, and so the frustration among people over there is: ‘The more things change, the more they stay the same.’”

For Mbaku, a far more accurate gauge of how successful the U.N. peacekeeping mission in Liberia was will be Weah’s behavior in Liberia’s next election. “In Africa, every time a standing president loses an election, he uses the army to try to stay in power,” Mbaku says. “Ghana is one of the few countries in Africa in which a standing president lost an election, and just left without stirring up trouble.”

Healing with Dignity

In the meantime, Taylor continues his efforts to lift Liberian citizens out of dire poverty.

It’s a daunting task. Today, Liberia’s population is estimated at 4.2 million with more than half of those people living in absolute poverty, meaning they can’t meet their minimum needs. Only one in six households has access to electricity. Indoor pumps or pipes are still rare. Most Liberian dwellings are constructed with mud and sticks. Other common construction materials include concrete blocks and mud bricks. Sheets of zinc, iron or tin serve as roofs.

Clearly, Liberia needs help, but Taylor and Mbaku insist that relief and development are two very different things. They say if Americans really want to help Liberians, they shouldn’t send money; they should go over to Liberia and build structures, like schools and healthcare clinics, that will allow local people to take care of themselves. “Those types of things are very good,” says Mbaku. “You go build a structure, train local people and let them run it. Now, sometimes they’ll run it into the ground, but it’s still better than just going over and giving them money. When you go over to Africa and just give people money, you are pressing them into a position in which they’ll just go out and consume.”

While Mbaku believes the ultimate key to Liberian peace and prosperity is government reform and educational opportunities, Taylor believes it’s equally important to help individual Liberians find meaningful ways to earn a living. “When Joel first contacted me, it wasn’t because he was starving; he contacted me because felt like his life didn’t have a purpose,” says Taylor. “His kids didn’t look up to him. His wife was not proud of him. He couldn’t market anything of value in return for money.”

Taylor’s mantra is: “When you find someone who’s in need, give ’em a job; give ’em something to do.” But these days, instead of doling out dollars to one person at a time, Taylor supports and advises local grassroots organizations that work directly with Liberian citizens.

And while Taylor has since modified the way he offers financial aid and would never advocate reaching out to the next potential scammer, he says he’ll always cherish the important life lesson he learned from Joel: “Poverty is not the saddest thing in the world,” says Taylor. “The saddest thing in the world is the loss of dignity. If we’re going to build these developing countries, we’ve also got to rebuild the individuals.”

Selected Sources

Liberia: CIA Fact Book

Liberianembassyus.org

Library of Congress

microdata.worldbank.org

BS Documentary Africans in America: Brotherly Love

BS Global Connections/Liberia

ICE Video Documentary: The Cannibal Warlords of Liberia