[Click on pictures to enlarge.]

I was born in Madrid because at the time my father was in the Ministry of the Navy, but then the family went back to Mallorca, which is an island in the Mediterranean, and my mother was from there. So that’s where I lived when I was young. After the proclamation of the Republic, the king had to leave and went into exile, and many of the generals and admirals resigned in protest. My father didn’t. My father stayed in the Navy and followed his career. He later became an Admiral.

That was during the Second Republic? Your father was loyal to the elected government—the democratically elected government.

Yes. And, he became Chief of the Balearic Islands Navy Base. So, we went to live in Menorca—that is a smaller island next to Mallorca, and that is where the main quarters of the base were. We were there when the war started.

The Spanish Civil War in 1936, between those loyal to the elected government and the fascist sectors of society.

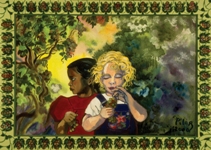

Yes. My father and forty of his officers—all of the officers—were murdered. They were sitting in a room and these people that I had seen arrive to the island—I will tell you the story a little later—opened the door, pulled machine guns, and killed them all. So we had to escape. But before that, when we were still in Menorca, I remember how wonderful it was and how, for the first time in my life, I was able to go alone everywhere because we were on the base and it was safe for children to play around. And I had never played outside on my own before. I had always had a nanny. But when we were on that island, that area was a place where nobody else could come in. We were able to go to the hills and the children were kind of free.

And then, all of a sudden the war came. That was a really terrible thing. I didn’t know anything about the war, and I remember being up in the garden and seeing people screaming and yelling, my father talking, and then the whole mood of the people would change. They would cheer my father, "Viva el Almirante! Viva el Almirante!"

The last time I saw my father, he was sitting in a wicker chair in the veranda with a book he was reading on his knees, and I was outside looking at him. There was a man with a machine gun pointing at him. He was not a sailor; he was just a miliciano, a member of a militia. Militias were groups of people that had sprouted all over Spain giving themselves the authority to do anything: robbing, confiscating and killing. I wanted to go to my father, but the door was locked, and the man did not let me in. Through the glass, I waved at him, and he waved back. That was the last time I saw my father. I was seven years old.

After that, we were thrown out of the house and had to hide in an attic full of discarded furniture. We could not open the windows because there many milicianos in the streets, both men and women, and they were shooting at anyone without reason or provocation. Our cook, Catalina, who had been with our family for many years and lived still with us, would take my younger sister and me for walks to help us relax a little. So on this particular day, we went to the harbor, and as we were sitting on a bench by the water an old derelict boat came to shore and a group of people, again men and women, came out shooting guns and yelling obscenities. They were dressed in black with red bandanas and kerchiefs. The women were wearing pants and red scarfs across their torsos. I had never seen women wearing pants at that time. They also had one bare breast hanging out. It was very shocking! I mean, it is something that you can never forget! These same people that we saw arrive were the ones that the next day went to the Castillo de la Mola, where my father and his officers were being held prisoners, opened the door to the room where they were together having coffee, an killed them all.

After that we had to escape, but we couldn’t go to Mallorca because it was under the power of the other side. We wanted to go to Alicante, where my father’s family was, even if we did not know if they were still alive. So my mother was able to arrange to go to Barcelona with the widow of one of the officers that had a house there, and afterwards proceeded to Alicante. We were already in the boat, sitting on blankets spread on the deck, when again a militia group boarded the boat and made us come down. They said that my mother’s friend had some papers hidden under her blouse, and so they shot her right there, in front of us, and left her body thrown over some rocks nearby.

We could not escape that day, but the next time we tried we were able to go and reach the Peninsula, first to Barcelona, and later by train to Alicante. The trains were very slow, and in every station, over and over again, they made us come out to check us. We had taken off our earrings because they would have pulled them off our ears.

They treated children like that too?

Yes. I had been playing with this young boy. He and his mother were also escaping. I’ll never forget this because I was making designs on paper, and he was writing things on it, just a plaything, like comics. And in one of these stations the militia grabbed these cartoons. They saw those writings and thought that they were messages or something in that order. And they grabbed the little boy and did not let him back on the train. This was a terrible thing because if you lost somebody at that time you may never find them again. So the train was already starting and a man from the train pulled the boy in, pulled him up. They were doing things that were totally nonsense. But what people don’t understand is that this was happening on both sides of the conflict. People think that all the bad people were on one side and all the good ones on the other one. This was not the case!

What do you think about the trend that we see nowadays in Spanish Cinema? They’re filming a lot of movies about the Civil War, but all the movies are from the perspective of the Republican side—that is, in all the movies the bad guys are the Nationalists, as in Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth.

I have never been for Franco. Many of my relatives were because Spain was divided. My uncles would criticize my father because he had stayed with the Republic. It was all mixed up like that, but I have lived in both places. I have been in the place when it was under the Republic, and I have been in a place when it was under the Nationalists, and in both places they were doing the same.

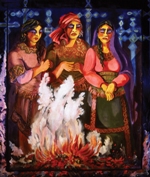

As a matter of fact, because I was at the beginning of the war on the Republican side, I think it was even worse. I suppose because it was the beginning, before things started to settle a little more to war. But I saw a lot of things. For instance, I remember from the attic where we were hiding, looking through the windows, there was a church across the street. And they were throwing everything from the church into the middle of the street and making a bonfire. I’m sure that the government would never have approved that. And on the other side, I have to say that most of the murders that happened on the Nationalist side would have been approved by Franco or by military people. So that is the difference.

I remember one example of Franco because somebody that had been there told me. Franco was reviewing soldiers and everybody was saluting. One of the soldiers refused to salute. His superior told him to salute and he did not. So, Franco didn’t say anything, went straight to the end of the line, went to his office, and said, "Take that guy and shoot him." That’s how he was. Some people, I guess, admire him for that. I think it’s just horrible.

Your father’s death had many implications for your life, including your artistic career.

Yes, when I was a child I always wanted to be an artist, and I was encouraged very much by my father who always brought me paper and paints and all kinds of things. But when he was murdered my artistic hopes practically ended because my mother was not inclined to allow her daughters to do anything. At that time it was thought that what women should do was to remain at home, or enter a convent, and amuse themselves with knitting, embroidering and sewing; even reading was not encouraged because it gave you too many ideas. I continued painting and sketching with the little means I had, but my work was not appreciated and was thrown away when they would clean my room. So, I was not encouraged, although I continued painting and doing other things like painting furniture and embroidering things that I designed, even dresses. When I was twenty-four, I met my husband and later got married, came to America and had three children. By that time I kind of had been brainwashed and thought I was too old to be involved with art. I thought that I had lost my chance.

But during all that time, you had continued creating things for your family.

I still continued doing the same. I would make things for my house and everybody thought they were kind of extraordinary. (Pilar laughs) I painted furniture. I designed my garden—I designed everything.

Then, when my son was fifteen years old, he wanted to take a photography class, and my husband, who was always trying to encourage me to get involved in art, said, "you should take a class doing something so you don’t have to go back and forth to get him." And so I did. I remembered that when I was at my grandparents’ house in the country when they were cleaning the ponds, there were many big piles of clay. And I loved to go and make things with the clay. My grandparents had a woodskeeper, and his wife was a potter, and if my pots or my figures would survive the drying—sometimes they didn’t—she’d fire them for me. So, I remembered these things and decided to take a pottery class.

[Click on picture to enlarge.]

Where was it at?

In Salt Lake. What they called the Art Barn then, but now it’s called the Finch Lane Gallery, a public place for art. My son was taking his photography class there. The pottery wheels were always very busy; there were too many people in the class. It was almost Christmas, so I started doing figures for nativity scenes. And I found out that I could really do them pretty well. So I didn’t do any more pots, and then I bought clay and started working on sculptures on my kitchen table.

Which was your first sculpture?

It is there, that monk on the window. I was remembering what I had seen in Spain, folk art, saints and peasants, small animals. I did not yet have confidence, but I started to like my pieces, took them to a gallery and they were accepted. It made me feel very good.

Which gallery was that?

The Phillips Gallery, which is a very good gallery, a large gallery in Salt Lake.

Instant success!

(Pilar laughs) That’s how I started my art. And then when I was going on trips, I couldn’t take my clay with me and I was missing doing art. So I started to paint watercolors. And my husband said, "Why don’t you go to the U and take a watercolor class?" And I thought about it and then I thought, "Well, I’m just too set in my own ways and I want to do what I want to do—and I will learn it on my own." (She chuckles)

So, you taught yourself how to paint?

I taught myself. I started to do watercolors. Later, my husband gave me paints, oil paints. And I have never stopped. This has become my life.

An obsession?

An obsession. Then I started to do my frames because I thought I was expressing in my frames something related to the paintings. And the frames, I always did them in acrylics. In the last few years, sometimes in the winter, I didn’t go to my studio in the back garden because it was icy and I decided, "I will just start painting acrylics because they don’t smell when I am painting inside the house." I like acrylics because there’s so many things that you can do. You can add textures that you cannot in oils. They are also good for me because I’m a painter that paints very fast. It comes out very quickly to me.

So you do much more painting now than ceramics?

Well, I haven’t stopped creating sculptures because I like to do them very much, but what happens is I am always having deadlines. They take a lot of time, and I never stop before I finish any particular work. So I don’t do them as often as I want, but I plan to work in sculpting again. I also do three-dimensional paintings on wood that are part clay, mosaic and objects. I like to try different things and I am always open to new ideas.

You were very successful when you took your sculptures to a gallery. Did the same thing happen with your paintings?

Well, I started by competing, taking my paintings to open shows where there’s a jury and they accept or not accept the paintings. Sometimes they didn’t accept them and sometimes they did. At the gallery where I was showing, they said, "I think you should concentrate on your sculpture. There are many more painters than there are sculptors." But I said, "I love to paint and I’m not going to be a closet painter. I want to do it." Well, almost immediately, another gallery started taking my paintings too. Now some of my paintings have gone to New York or to Florida or to Washington, D.C., and of course to the West.

Let’s go back to Spain. How do you think that being raised in Spain has influenced your paintings?

I always say that in Spain, if you are receptive to art you get an education without even knowing it because you are surrounded by art. You are exposed to art all the time in beautiful churches and cathedrals, palaces and castles, in the streets and the squares, and, of course, museums. In the past, the kings of Spain were great collectors and sponsors of fine art. I never went to a town without visiting its museum. I remember once when I was very young, I spent a month in Madrid and visited the Museo del Prado every day. Even in my grandparents’ home they had a couple of paintings by Velazquez. They lived in a palace by the old wall of Palma, and the house itself was a work of art.

And how do you think that is reflected in your paintings?

I think it is reflected very much. I think one of the things that really started me concentrating on my art was the fact that, even though I liked to be in Utah, I was missing my country very much, and all these feelings for my country came out in my art. This is why I think being Spanish is one of the biggest influences in my being an artist.

I see the Mediterranean in the colors. They are so vibrant!

Yes. The places where I have lived have influenced my art, and so has Utah, especially its southern landscape. I also have a lot of influence from Mexico because I have a house there and have spent much time in that country. One of the things I admire most is that the really good Mexican artists and craftsmen, in whatever they do, they don’t show inhibitions and do what they feel at the moment. And this is the basic thing of my art. I hardly ever plan for sure just how a painting is going to look or what I am going to do. Even when I plan it, as soon as I start painting, it comes in different ways. It just happens and develops.

I see a Mexican theme clearly in your Virgin de Guadalupe.

What is so exciting and wonderful about being an artist is that wherever you go, if you are so inclined, you see things. You don’t have the time to do all the things that could be done.

So, you never have a writer’s, a painter’s block?

Never. And I don’t have writer’s block either. When I write, I write.

You were working on another book.

I have started, but this project I am doing right now is not letting me dedicate very much time to the book at this moment. But I started because I enjoy it. I always have been very fond of writing in Spain, but when I came here, I thought I couldn’t write in English. When the University of Utah published My Kitchen Table, that kind of gave me permission to keep on writing.

Tell us about this project with the University of Utah that you’re working on now.

Well, the University of Utah is having a new building for the Humanities. And they say it’s sort of going to be the hub of the campus. I was honored to be asked to do a large painting for the lobby, and this is what I’m doing now.

Your house is full of paintings, like the studies for that big one.

It’s because I couldn’t work in my studio, because the ceiling is not high enough. But my house in an old house—it was built in 1893, and the ceilings are pretty high. So, that’s why I’m doing it in the dining room. ( Pilar laughs)

Let me see. You now have six related paintings in your living room and dining room. How tall will the final painting be?

The final painting is in two pieces, but they will be in the same frame and they will be eleven feet by eight feet. They are going to have in some other gallery a collection of seven paintings that I did a while ago. I didn’t want to sell them separately. They have got them for the building too.

How do you like working on commission since you’re so free in your art?

Well, it worries me a little. But I am very optimistic, so I just go ahead and do it anyway, hoping for the best!

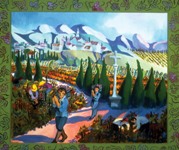

What kind of suggestions did you get before starting this project for the University of Utah? "We just want something to represent the people in the Humanities"?

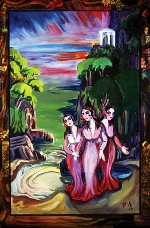

Yes. They wanted a Utah—a Southern Utah landscape—and they wanted a diversity of people that would look like they belonged to the Humanities. People related to writing, poetry and maybe scientists, because all of them belong to the Humanities. So that’s what I have in the paintings that you see in the dining room. They are figures that I have tried to do with that kind of thing in mind. And then I decided to incorporate the Muses because I think that the Muses have not been given the proper attention in this country and we need the Muses as inspiration. So, I put the Muses in my "try-out" paintings, and when I showed it to them, they thought it was a very good idea. Besides that, it makes the paintings more glamorous.

[Click on picture to enlarge.]

Exactly, with all the flowing dresses and the flowers in the hair.

Yes. Other people are dressed in their normal clothes, but the Muses are dressed in their original Greek style, dressed in white.

It looks wonderful, and it is definitely a Southern Utah landscape. With all your love for Spain, was it difficult to get used to living here?

Well, no. It was different, but it was not difficult. It was interesting. My husband, almost immediately, started taking me down south for weekends or when we had free time. This is the reason why I like Southern Utah so much. We went to Moab. We went to Zion’s, to Bluff, to Arches, to Capital Reef. We went everywhere. I think Utah has the most stunning landscape. We are so lucky to have it!

And the color!

And the color! I am a person that likes color, so that was just perfect for me.

And then, I have to say, I have three children and I have a family—there was no reason for me to be unhappy. I love my family, my house and everything, but in spite of all of these, I have to say that I have been here fifty-one years and I am still so Spanish—I am more Spanish than the people that stay there!

And you go back quite often.

I try to go once a year, maybe a year and a half. My youngest daughter, Maggie, lives in Barcelona. So I go there.

At the same time, you are firmly ingrained into the culture, the community here in Salt Lake.

Yes. When I arrived here I already had friends waiting for me because my husband was from Salt Lake and all of his friends accepted me right away. And they have been very good. Now, some of them are gone already and their children are my dear friends. This has been so since the first week that I arrived in Salt Lake and so I didn’t feel alone.

And then another thing that happens is that, being an artist, you meet a lot of wonderful people because people that like art and poetry and the Humanities are wonderful people. (She laughs)

I think that life is like a mirror so that if you look at it smiling, it gives you back smiles.

Yes.

And you have this optimistic and friendly personality so it gives you back the same. But let’s go back to painting; I would like to know how you would qualify your art?

Well, it’s difficult for me to say, but the thing that I like more in my art than anything else is color and expression. I’m not exactly concerned about making things look exactly as they are. I like to make things look the way I like them to be or the way I like to think they look. For instance, I paint a landscape of where I have been but I am not really there at the moment. I do it from memory. And I don’t claim that they are exactly what they are, but the way I feel they are. So, I think my art is realistic, but it is my own reality. It is not exactly a copy of what is there. It is my interpretation of reality.

And of course, being self-taught, I never was taught techniques but read an awful lot of art books. And like I said before, every time I go someplace, I always go to see museums, and I think things stick to you. For this reason, sometimes people tell me they see something of another artist in me. I think that when you are receptive to nature and to other people’s art, you sort of keep it in you. You collect it inside you. Then it comes at the right moment when you need something, when you need some color, when you need some impression. It just comes out. It’s a very spontaneous thing.

Do you think your art has evolved over time?

Well, I think I have learned, and I am still learning, but I think almost every artist evolves. I don’t like to think of people repeating themselves forever. You would think that some of the things I do now look almost the same, in the way of expression, as things that I did many years ago. So, it changes sometimes and then it goes back to the roots again.

Of all the different art manifestations, is there something that you prefer to do?

Probably the thing that I like most to do is people, but since I also have to sell, and people like to buy landscapes, I do landscapes.I am very lucky to say that when I do landscapes, I enjoy it as much as when I do people. This is why I never do things that I don’t like to do. I like if I do a landscape or if I do a still life, or whatever, I do it exactly the way I feel it. So, when people ask me, "What do you prefer to do? What is your favorite thing?," I say it is the thing I am doing at the moment.

And is there one piece of work that you are really proud of having done? Is there one that you look at and think, "Oh, this looks really, really good—this is my favorite"?

Well, there’s one collection of sculptures.

The nativity scene?

Yes, I’m very proud of that. It is not only that I think the figures are good, but there are many of them. There are about twenty-seven or twenty-eight, but some of them are multi-figures.

And how tall are the pieces?

The tallest ones are twenty-four inches or thirty-six inches high.

And where are they located now?

They are at the permanent collection at the Fine Arts Museum, but from time to time, they come out of retirement. (She laughs)

Wasn’t it Christmas when they were out?

Yes. Last Christmas they were out because the LDS Museum borrowed them from the University and I went to put them up at the LDS Museum across from Temple Square.

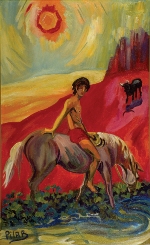

It took me a long time to do them, and usually I am proud of a painting if I keep it long enough to really become fond of it (She laughs). Like, for instance, this painting here, the boy on the horse. My husband didn’t let me sell it because he liked it so much and now I really don’t want to sell it.

[Click on picture to enlarge.]

You had to stop painting because of your gender and because of the way Spanish society used to behave toward women artists. Do you think that male and female artists paint in different ways?

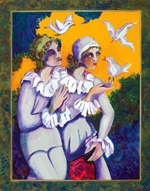

I think every artist paints in a different way. Well, no. There are groups of artists that paint in a very similar manner of each other. But when an artist develops his or her own personality, I don’t think it matters whether he is a woman or a man. They have their own special way of painting.

So you wouldn’t be able to look at a painting and say, "This is a woman, or this is a man"?

I have to tell you that many times people tell me that they thought I was a man, that they thought my paintings were done by a man.

Did they say why?

Well, because they are strong. I’m not very sentimental. I hardly ever put my faces smiling. And I don’t make them very delicate. So, no, I don’t think you can tell. It depends on the personality of the artist, not the gender. I would say that in the case of the paintings of some of the Impressionists, you could not really tell if they were made by a man or a woman.

You have told us about your origins and about where you are now. Is there anything that you would like to accomplish in art that you haven’t yet?

Absolutely! (She laughs) Art doesn’t have an end. There’s always something that you’re not going to have done that you wanted to. There’s more and more and more and more. One of the things that I’m sorry I have never learned is wood carving. I would love to do wood carving, but I probably won’t because, where is the time? Now I am so late! I am working harder now because the time is shorter! I am working double time. (She laughs)

What do you think about the state of art in Utah?

I think Utah has wonderful art. I think there are very many good artists. There is an abundance of very good art here.

What do you think is the reason for that?

Well, I know for a fact that art has always been appreciated in Utah—which doesn’t mean that it has always been well-paid! But it has been important. And, for instance, I am on the board of the Utah Art Council right now, which was the first in the Nation. I think when the LDS Church first came here it gave much importance to the arts. Not only to the visual arts, but also the theater and to music and writing.

I wonder if this has to do with this scenery. It is so beautiful it has to impact people.

I think that could be too, but I think Utah was a very isolated place, and the LDS Church started these organizations. I know that because one of my husband’s uncles was first sent to New York and then to Paris to learn how to paint, and that was the Mormon Church that was doing it. So, the arts have always been important in Utah, and this is the spirit we should try to keep alive. For instance, you said that you like the Art Party that I give in this house every year.

Yes.

That was my intent. That is what I had in mind when I started doing it. I wanted to do it because, as much as I say that in Utah the arts are appreciated, we’re not appreciated by a majority. The majority of the people are not involved in the arts, and many of them, I suppose, don’t often go to see art at a museum or a gallery.

Would you explain what Art in Pilar’s Garden is?

(Pilar laughs) Well, this started because I have a garden, and it is a little different. It looks Spanish. Every spring there is an organization that likes to show gardens, and they do it for a benefit. They asked me to participate showing mine, and I accepted. People who visited were not going into my house, but I noticed that they always looked through the windows at my art. So I thought having an art show in my garden would be a good way to entice the ones too intimidated to go to museums or galleries and show them how really exciting looking at art is. I shared this with some of my artist-friends and they said it was a good idea, especially because it was not going to be in their homes (She laughs). So that was the beginning. I called it Art in the Garden. Every year it grew more and more. Then some other local artists decided to do the same and called it the same thing. I was plagued by continuous calls asking if my show was going to be somewhere else. So I changed the name. It is now Art in Pilar’s Garden. We have done it for fourteen consecutive years the second week end in June.

It was so successful that you have even had concerns about security…

Well, I have never had any problem. I mean my house—my whole house—has been open. I always ask some friends to be aware of what is going on a little bit. But, lately, the last two or three years I have had so many people—I never thought I would say this—that were coming mostly because it was a party, you know, not because they wanted to see art. I decided I was going to make them buy a ticket. This last year was the first time that we did that.

Because you had hundreds of people…

We had fifteen hundred people for three evenings, and it was only three hours every evening. So it was very, very populated. So this last year was very good because it eliminated some people who really didn’t come for the art, but for the fun of food and drinking. Now we have the people that come for the art. Not necessarily to buy art, just to look at it.

To enjoy it.

To enjoy it. To appreciate the art. Because a lot of people that enjoy art, maybe they cannot afford to buy it, but feel good when they see it. Now the funds that we get—we asked the Utah Arts Council to collect the money—go to grants for individual artists.

And you invite other friend artists to participate.

I have so many people that want to come! They don’t realize that my house is not big enough to display all that art. So I have three or four that come more often, and this year one of them is coming from Italy. This is the second time that he will come.

It seems to me that you are very interested in promoting art, in educating people. What do you think is the role of schools in this aspect?

I think the role of art is extremely important in the schools because it makes students think of something that is enjoyable so they don’t become destructive. And besides that, I think that once students are involved in art, they like it very much. They dedicate themselves to something they can do after school, and it gives them an opportunity to do something that is valued. You know, my husband used to say that he had never met a child that was involved in the arts that would become a delinquent. I think the schools should really think about that. And I believe that even if they spend money in classes now, they probably save a lot later on.

Later on in jails, yes. Although as you so well demonstrate, people can become artists at any age. I have a lot of students that say, "Oh, no, I’m too old to go back to school. You know, and I’m twenty-two or twenty-three." What do you say to people that are afraid to start things because they think they are too old?

Well, I think they are mistaken. (She laughs) You know, you are never too old to do what you like to do. And this is what I say, this is what directs my life every day. The only thing that happens is the older that you are, you have to accelerate in order to do the things you want. (Pilar laughs again) So, if anything, it is more urgent that you start doing what you like.

Pilar follows her own advice. In the last decades she has not wasted any time. Her paintings and writings await her. So, we will finish our conversation and let this amazing artist go back to doing what she loves most: creating her own reality in a neighborhood in Salt Lake City.

as soon as they walk up her front steps. The personality and creativity of this Spanish-born, Salt Lake City artist cannot be confined to canvas or paper, as they overflow constrictions to permeate everything she touches: the blue door with a pomegranate tree on it; the terracotta walls with ceramic angels, grape vines covering pergolas; even rose shrubs are more vibrant here. Light, color and raw energy are three constants in the life and work of Pilar, a woman who after being forced by a patriarchal society to stop creating art rediscovered her true passion in Utah.

as soon as they walk up her front steps. The personality and creativity of this Spanish-born, Salt Lake City artist cannot be confined to canvas or paper, as they overflow constrictions to permeate everything she touches: the blue door with a pomegranate tree on it; the terracotta walls with ceramic angels, grape vines covering pergolas; even rose shrubs are more vibrant here. Light, color and raw energy are three constants in the life and work of Pilar, a woman who after being forced by a patriarchal society to stop creating art rediscovered her true passion in Utah.