Fall 2008, Volume 25.1

Art

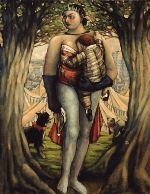

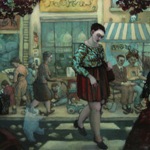

Lori Nelson

Painting From This Remove

Lori Nelson grew up principally in Grand Junction, Colorado, whose western, quasi-urban topography—a mall, ramblers, orchards, horses, a river, as well as abandoned industrial warehouses and factories—serves as literal and metaphoric backdrop for many of her paintings. At eighteen, she moved to Salt Lake City where she saw more malls and bigger factories and where she began sketching a narrative of her (and her neighbors’) life in her drawings, eventually earning a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from the University of Utah. She has been a creative presence in the arts of the intermountain West and shown her work in numerous galleries and juried art exhibitions, such as the Delores Chase Gallery (Salt Lake City), the Marshall Arts Gallery (Scottsdale, AZ), the Coda Gallery (Park City and New York), the Western Colorado Center for the Arts (Grand Junction), and the 2002 Utah Juried Olympic Exhibit, among others. She is the recipient of a NEH/Utah Arts Council grant and a widely sought guest lecturer along the Wasatch Front. These days she has swapped the Rockies for Brooklyn, where she currently works and lives with her family. She is represented by Phillips Gallery in Salt Lake City, Utah, and Brenda Taylor Gallery in Chelsea, New York.

My work has become about distance and its variety of forms and designs.

In painting, as in life, I am inevitably drawn to the awkward, the second-hand, the small: the smile that betrays something, the person with an insignificant job to do, a slight sideways glance. In these, the potential reaction is always in question and an element of danger exists in a microscopic moment. A storm is never far off on the horizon.

[Click on paintings to enlarge.]

In my work, the seemingly calm subjects usually conceal a world of heartache almost accessible, never totally legible. I hope to always leave space for the viewer to decide on a personal story for the subjects in their small situations.

I myself have my own story for each painting, often autobiographical. However, my own interpretation is not necessarily the "true" or "real" story. As in life, I can offer only my analysis amid several possibilities as to what the conflict, drama, or history of a subject may be. Once created, I want my paintings to exist independently of me. I have more than once changed my opinion on a subject or situation in my artwork. This changing of stories is desirable to me. I never want my paintings to become static, although they may be still.

I paint in the attic of an echoing house, high above my neighbors who politely keep their distance. I effortlessly spend days without actual contact with anybody other than my family, who may know my back better than my front (which image will someday make for a wry family portrait). This state where I live is itself a national anomaly, so removed by strange customs and practices from the rest of the country. The Utah landscape I confront also exerts itself little to invite habitation, but rather defiantly retains its plain expanses of empty, save the incidental factory, our faltering hive of industry.

Called a "regional realist" by Robert Olpin in Artists of Utah, I find that a solitude particular to this place seeps into my canvasses, back to front. Through a vast Great Salt Lake/Northern Utahn landscape of haphazard warehouses, stacks, and unswimable waters, my subjects wander together without touching in any meaningful way. Those subjects, twice removed from reality by their composite features and remembered surroundings, acquire yet another layer of removal through metaphor and visual wordplay. I rarely portray anything literally, but rather point to a possible narrative.

My work could be dismissed as funk-inducing tableaux of a loneliness capable of driving one to seek comfort in crowds, drink, and/or the Internet, if it were not for the possible discovery of a human resonance or, ironically, a kindredness with the subjects. We are essentially all in this alone, and does it not feel good to know that our misery is shared, if not in a Brotherhood of Man sort of way, then possibly in the context of unadulterated schadenfreude? (Of course, it can’t hurt that I deliver my work gift-wrapped in warmth, replete with healthy cheek and bosom.)