Winter 2005, Volume 22.2

Essay

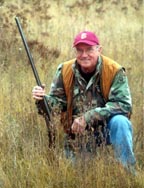

Ron McFarland

For the Birds

Ron McFarland earned his PhD at the University of Illinois. He teaches literature and creative writing at the University of Idaho. His books include The World of David Wagoner (1997), Understanding James Welch (2000), Stranger in Town: New & Selected Poems (2000), and Catching First Light: 30 Stories and Essays from Idaho (2001). His short story, "Different Words for Snow," won the Dr. O. Marvin Lewis Essay Award in 2000 from Weber Studies.

Read other work by Ron McFarland published in Weber Studies: Vol. 8.1 (fiction), Vol. 12.1 (poetry), Vol. 15.2 (poetry), Vol. 17.0 (essay), Vol. 17.1 (fiction), Vol. 19.3 (fiction), Vol. 23.1 (Fiction).

One spring afternoon in 1952, in a field behind my family's project house in Cocoa, Florida, I took a deep breath, let out half of it, then squeezed the trigger and shot a mockingbird. Of course when my mother reluctantly agreed to allow me the fulfillment of my boyhood dream, a Daisy Red Rider lever-action air rifle, I had promised her I would never dream of committing such an atrocity. Yet here I was, just a handful of months after Christmas, dispatching one of our feathered friends and breaking my word as well. The Daisy Red Rider model looked, I thought then, convincingly like the classic 1894 Winchester .30-30, standard rifle of the John Wayne movies.

My feelings on that occasion were probably less complex than I remember them. Surely elation was foremost. Of course, I had not shot the bird on the wing; nevertheless, I recall that I shot from a pretty good distance (whatever that means for an air rifle—say 20 or 30 feet), and the bird was perched in what we used to call a scrub oak, probably a little blackjack. I was impressed with the power now at my fingertips, and certainly I did not think of what I had done as an atrocity, and, to be coldly honest about the affair, I still do not think of it as such. There is, at least, another name for it. So what I felt then, initially, was elation and a sense of power. Those tiny copper BB's could be lethal. The heck with warnings to the effect that this rifle could put someone's eye out. This thing could kill a middling sized bird, and if that, then probably frogs, and quite possibly even snakes.

So, no, I was not filled with remorse, although, I submit, I may have felt some twinge of guilt. I do not wish to make false claims on behalf of my conscience. I felt bad because I'd promised my mother I would not shoot at any living thing, but my joy was certainly greater than my regret. I promptly buried the evidence of my misdeed.

Last week I read in a newspaper column that the mockingbird song "Listen to the Mockingbird" was written in 1855 for bachelor President James Buchanan's charming and beautiful niece, who had violet eyes like Elizabeth Taylor. The composer was Septimus Winner, who also wrote "Ten Little Indians" and "Whispering Hope" and who took to himself the unlikely pseudonym of Alice Hawthorne. My father has always been a singer, has a wonderful tenor voice, and I knew "Listen to the Mockingbird" back then, and I also knew the popular song written by Vaughn Horton, sung by Patti Page in 1950:

When the sun in the morning peeps over the hill

And kisses the roses `round my window sill,

Then my heart fills with gladness when I hear the trill

Of the birds in the treetops on Mockingbird Hill.

I knew those songs in 1952 when I shot that mockingbird, but they did not echo in my mind to warn me against what I was about to do, nor did they come back to haunt me because of what I had done. I checked the internet and discovered there is a Mockingbird Hill in Knox County, Tennessee, elevation 891 feet. There is also a Mockingbird Hotel in Port Antonio, Jamaica. What if I had thought about all of that in 1952, when I was ten years old? "Oh," I might have told myself, "that mockingbird!" Then I probably would have gone right ahead and pulled the trigger. I was a merciless little boy.

I wonder now if that wasn't when our mother bought us our first parakeet. At the time I did not give the phenomenon a second thought, but retrospectively, given our mother's lifelong phobia over avifauna, her decision seems remarkable. Why would she have done it if not to implant in me, her firstborn son, and in Tom, who might fall under my malevolent influence, some compassion for our feathered friends? Our mother was simply terrified of birds, and Petey (I think his name was, if in fact it was a male), our powder-blue parakeet, was no exception. She would not get near its cage, and, of course, feeding the feathery nuisance and cleaning its cage fell on our shoulders. She would pretend courage. She would call out "pretty bird, pretty bird," which Petey would appear to imitate in some fashion. But we were under no circumstances to release the parakeet in her presence. On those two or three occasions when Petey gave us the slip and flitted into the kitchen, Mom was instantly out the door. Twice I returned from school to find her standing in the front yard, refusing to re-enter the house until someone retrieved Petey and restored him to his perch. On one occasion she said she had been outside for at least two hours. I know we acquired at least one other parakeet somewhere along the line, but I forget its name.

These birds were not of great moment in our lives. Perhaps Mom introduced them simply to distract us from our other pets, the irksome black mongrel we called Scamp, for instance, and the forever-underfoot tabby we sarcastically named "Mother Cat" because she delivered a litter on the front porch and refused to take even the first lick to bring them into the world alive. Our preference was for more exotic species, box turtles and gopher turtles, various snakes (eastern ringneck, scarlet king, common garter). These had an uncanny inclination to escape on us, and it was only in later years that I was to learn that our mother had generally assisted them in their break for freedom.

Cocoa was and doubtless still is a great place for birdwatchers, located as it is between the marshy St. John's River to the west and a pair of lagoons, the Indian River and the Banana River to the east, after which comes the ocean. There were bird sanctuaries around even when I was a boy back in the environmentally unconscious Fifties (we were more concerned about nuclear attack). I had a friend named Julian who actually was a self-proclaimed birdwatcher, and he had the binoculars, field guide, and notebook to prove it. Being a young birdwatcher was not a particularly quick avenue to adolescent popularity back then, but perhaps that has changed. Somehow I doubt it. To make matters worse, Julian was our Presbyterian minister's son, and he was not the rebellious PK who Norman Maclean depicts in A River Runs through It, but a good boy who played clarinet in the high school band. Once when I visited him, he showed me a jar in which he had collected all of his baby teeth. We were never close.

On subsequent occasions over the next several years I discovered that my air rifle was indeed a reliably mortal instrument. I slew any number of dragonflies, frogs, and snakes with no more regret than one might have for swatting a fly or squashing a mosquito, skewering a nightcrawler or poisoning a butterfly with carbon tetrachloride prior to pinning it on a board for display. When I turned eleven and joined Boy Scouts, I subscribed to Boy's Life, which I read avidly. In the back pages among the ads was a cartoon strip purporting to record a true-life adventure that befell members of a Scout troop on a hike. One of the kids slipped and fell. As he grabbed his ankle, a diamondback rattler suddenly coiled and prepared to strike. He was helpless and would doubtless have died from the snakebite had not one of his fellow Scouts brought along his trusty .22 loaded with Peters High Velocity cartridges. The kid must have been a darned good shot, because in the comic strip it showed that he shot the rattler right through its gaping mouth. From the day I read that ad, I began lusting for a .22.

Now, of course, I realize the improbability of that scene, but I did not perceive it that way then. No way. It seemed altogether likely that at least one of those Scouts would be packing a firearm on a hike, even though any scoutmaster I ever met would have absolutely forbidden such a thing. It also seemed to me that with a little practice I, too, could dispatch a rattler by shooting it through its gaping mouth at some thirty or so yards. One would simply line up one's shot between the bared fangs. The rattler would compliantly hold its jaws apart for several seconds before striking so that I might crank a cartridge into the chamber, slip off the safety, aim carefully, and fire with deadly accuracy. In bed, sometimes I would mull over just whose life I might save—Bob's, Mike's, maybe Don's, our obnoxious bully of a Senior Patrol Leader. Then he would owe me and would stop calling me "shrimp" or "Mac Fart-land." Later, I began to save the lives of various girls in my dreams—Sharon, Susan, Myrna.

Perhaps I should confess that at the time it would not have occurred to me that the victim in the Peters ad, the kid grabbing his twisted ankle, would by any means have been a goner had the rattler struck him. This was Florida, after all, and we were well trained in the arts of first aid for snakebites: apply tourniquet between snakebite and heart (textbook illustrations always featured snakebites on such convenient body parts as lower arms and legs); cut small X's over the two fang marks; suck blood and spit out mixture of blood and venom. Simple. Most of us had witnessed various simulations of the technique in Saturday matinee Westerns. If John Wayne could do it, we could do it. Only, of course, we should not suck out the venom if we had an open sore or cut in our mouth. Also, if a coral snake were the villain, as opposed to a rattler or a cottonmouth water moccasin, we would be obliged to cut off the limb, inasmuch as their venom, like that of their cobra cousins, affects the nervous system. And it works very quickly. We would have no time for indecision or squeamishness. Lop off the finger or hand first and ask questions later. The books featured no illustrations of such an amputation, but we all knew how to do it: first, apply tourniquet. We had great faith in tourniquets.

Nevertheless, the positive need for a .22 (not to mention a large box of Peters High Velocity .22 long rifle ammo) was obvious to me. I reasoned that if I had a .22 I would probably not have to resort to the unpleasantry of treating someone for snakebite. Of course there would have been a trade-off, had the treatment involved Sharon, Susan or Myrna, but that was another matter. (Perhaps I should note in passing that the first aid techniques for dealing with snakebites that we were taught back in the Fifties are now thoroughly discredited.)

It was for my thirteenth Christmas that Santa delivered a brand new, single-shot, bolt-action Remington .22. The tradition in my family was that Santa's gifts were placed under the tree unwrapped, while Mom and Dad's gifts (usually some nefarious item like a shirt or a pair of blue jeans) were wrapped. Of course we'd known the mythical nature of S. Claus since we were five or six years old, but we enjoyed helping our parents sustain the ruse. The advantage I had over my brother Tom, two years younger than I, was now unbridgeable. My trusty air rifle was consigned to a dark corner of the closet.

On the other hand, I could not just grab my trusty .22 and tote it across the drainage ditch and into the field. (We'd always called the twenty or so acres of palmetto and scrub oak, along with a scattering of long-needle pines, "the field.") The .22 could not be fired in the field. It was strictly for target practice under Dad's supervision out at the city rifle range, and he hardly ever seemed to have time. Somewhat to my dismay, and very much to my surprise, I turned out not to be quite the marksman I'd assumed I would be. Years would pass before I would have another opportunity to gun down a bird, and when that opportunity came, I would be shooting not an air rifle or a .22, but a more appropriate (given my lack of sharpshooterly skill) scattergun.

The opening of the 1966 dove season in eastern Texas found me in the field with one of my marginal students. It was one of those uncomfortable situations wherein one finds oneself belatedly fraught with mixed emotions. Steve absolutely insisted I take the lead through the jungle of undergrowth so that I might have the first shot once the birds flushed at the far end. Never having shot at birds on the wing before this, I was hoping to conceal my lack of experience, so that was my initial concern, but now, miles away from town and on our own, I began to feel uneasy about another matter. The fact was that poor Steve, the number two wide receiver for the Bearcats, was doing miserably in my survey of American literature, D-type miserably, to be exact. One more bobbled exam could very well have been his undoing, the ultimate dropped ball, the last broken play. I began to imagine his 12-gauge Browning peppering my tender back with double-ought buckshot he would claim to have accidentally pumped into the chamber instead of the relatively benign #8 birdshot. It was a difficult afternoon, and I found myself frequently smacked across the face by rogue branches I'd have handled easily enough had I been able to keep from turning my head so frequently to see what Steve was up to.

As it turned out, Steve was up to nothing, except perhaps a futile effort to curry favor with his young English instructor. We eventually ended up near a tank or small watering pond, which attracted a flock of dove near dusk. Steve dropped three, as I recall, and I unleashed the fury of my father's old single-shot 16-gauge Remington just once, in vain. Steve managed to scrape through the course with a solid D, and we parted on good terms. I remember thinking, "D is for Dove."

Five or six years later I found myself wading above my knees in the nearly frozen marsh of Lake Chatcolet in the Idaho panhandle. D might also stand for Duck, I guessed. Because my three hunting partners and I could not boast of so much as a rowboat among us, we were compelled to don waders, and because I could not boast of a set of waders, I was compelled to wear Tanner's only slightly leaky hand-me-downs. In the event, the leaks were not so problematic as the fact that Tanner's feet were size 12, while mine were scarcely up to an 8. "Room to grow," he suggested. I should add that we did in fact have a dog with us, Leo's yellow lab, Babe, but as it turned out, the designation "Labrador Retriever" fit Babe about as loosely as Tanner's waders fit me. She was not at all inclined to jump into the channel after one of the rare mallards we managed to drop that morning from the overly blue sky. Good gray cloud cover would have kept more of the birds in range, and on subsequent opening days we were luckier. With ducks, that is, not with Babe, or later, with her addle-pated daughter, Ginger.

"Go girl!" Leo commanded after Tanner dropped a green-head into the channel.

Babe lowered herself into the muck at our feet.

"Go!" Leo tossed a stick in the vicinity of the downed duck.

Babe plunged into the icy channel, nosed the mallard aside, and retrieved the stick. Later in the morning the current drifted the duck closer to our side, and after plodding back to the shoreline for a length of tree limb, we were able to reach it. When Bacil dropped a small teal practically at his feet, however, Babe gleefully leapt to the bird, clamped her teeth on it and released it only after considerable threats and curses. We went out after ducks for several more years, and in fact I managed to down a few, but I never became much of a duck shooter.

Most of my successes and embarrassments have come with upland game birds and grouse. Bacil introduced me to the glories of road-hunting for grouse on Skyline Drive, just twenty or so miles north of where we were living in Moscow, Idaho. While he had grown up in Texas, Bacil had taught folklore for many years at the University of Hawaii, and he regarded his return to the contiguous states as an invitation to return to the hunt. As a folklorist, he possessed a vivid imagination and quick credulousness that made him a fascinating companion in the field. A certain deserted miner's shack outside Laird Park, for example, he assured me was haunted. He had seen a local anthropologist's plaster footprint casts of Sasquatch (a.k.a. "Bigfoot"), and he was a believer. He was one of the first scholars to have traced the literary Dracula to the historical Wallachian tyrant, Vlad Tsepesh. One memorable afternoon Bacil proudly displayed for Tanner an unusually plump duck of uncertain species he had bagged off some county road. It was a domestic bird. I am sure it was quite tasty.

Forest and spruce grouse are an obliging bird that prefers to hang out along the edges or in the middle of old logging roads and that is inclined to wait for you to shoot them. On the wing, they are a challenging target, as they are fast and are quick to blend into the trees. On the other hand, they are inclined to jump onto the lower branch of the nearest pine and freeze, believing they are camouflaged more fully than is actually the case. In short, they are generally easy prey, and their meat is white and delicious. I've always preferred them to field birds like partridge and pheasant. Grouse are pleasant to hunt. It's a stroll in the woods, a gentle amble along abandoned logging trails. Some hunters like to use .22s; others use handguns. I like to eat them too much, and I am too poor a shot, to be that sporting. You could probably knock them down with a slingshot as often as not, and many a hunter has tales of stunning a fat grouse with a stone, then wringing its neck and cooking it for an unanticipated feast over the campfire. Their fabled cousins, the sage grouse or prairie chicken, easy fare for western pioneers, are now dwindling alarmingly. Early accounts told of these birds ground under the wheels of Conestoga wagons.

Aside from occasional missed shots, I have no embarrassing stories to relate about my grouse hunting ventures, except, of course, for the time that I tried to eject a shell from my father's balky 12-gauge and shot a hole through the floor of the Datsun. I did manage to miss any vital parts of the vehicle, and for a couple of weeks I was able to conceal my mishap from my wife, but eventually she found me out and regaled all of our friends with the story.

My upland game bird hunting has been more conspicuous for its moments of folly. The chief error, I believe, occurred the morning I was hunting quail with my pal Tanner and blasted the radiator of that same Datsun. Limping back to Moscow (thanks in part to Tanner's Thermos of hot chocolate), we were headed straight to the radiator shop, where I was hoping a quick patch job would repair the ravages before my wife discovered the crime, when we encountered Tanner's wife. My cover was blown, and my wife soon had another story for the cocktail parties.

Of course I have made many more inept shots out there in the field than I have on the grouse trails, but that's nothing. It happens even to the best of shooters. And then, too, I have made some shots worth bragging about. Modesty forbids. Perhaps my worst day was the afternoon I scored a double on an unfortunate brace of meadowlarks. I was hunting gray or Hungarian partridge, and I'd worked my way uphill through heavy weeds and star thistle when two birds suddenly leapt from behind a basalt boulder. Blam-blam! Just like that. Rarely if ever has my shooting been more accurate. Mind you, these lovely songbirds are considerably smaller than partridge, so it could be justly averred that my marksmanship was on that occasion altogether praiseworthy. I left them where they fell, taking the bird hunter's usual consolation, when he cannot find his prey, in the notion that I was helping sustain the coyote population.

It was partly this misdeed that prompted me to write a poetic tribute to the small birds of the world about a year later. My skills as a poet do not usually run toward the lyrical, but this poem turned out to be a "song" of sorts, and I titled it after a quotation from St. Francis of Assisi, when he experienced a mystical vision upon seeing "a multitude of birds" fly off in the shape of a cross. It is a winter poem:

Sing now the desperate dance of small birds.

Sing where the quail collect after snowfall,

the mud-guttered borders of roads where the last

hard grains of wheat lay heaped with the gravel.

Sing the wren's last colorless song,

the solitary vireo's slow, cold slur

by the roadside sifting old brown bags

for crusts or bread crumbs, or perhaps

among the shards of bright green glass

a sip of wine, a claret deep as blood.

Sing then the cunning of sparrows which look

like nothing but dark little rocks,

for they will endure, and the starling

whose song is the echo of anything,

and the waxwing, gregarious feeders.

Sing warblers and blackbirds perched on the edge

of winter with ice clinging fast

to their wings, with plentiful seed

lying deep, with songs frozen hard into words.

Sing now the dance of small birds.

Unlike most of my efforts, this poem was accepted the first place I mailed it, a little magazine out of Huntsville, Alabama, called Poem, and it appeared in 1980. Later, I included it in a couple of my books, and later still, in December of 2000, Garrison Keillor read the poem on his show, The Writer's Almanac, so now when I read the poem I hear not my own voice, but the distinctive tones of Mr. Keillor.

Of course, birds, including grouse, appear fairly often in my poems, but I'm not likely to turn out a celebration in the mode of Keats's "Ode to a Nightingale" or Shelley's "To a Skylark." My birds tend to be pretty common fellows, and I've never gotten Transcendental with them. Would one be likely to encounter a vireo pecking beside the roads of northern Idaho in the winter? Perhaps not, but I did consult a field guide when it came to their song, and it's true that those noisome starlings are great mimes. A dozen or so years later, when I slipped a pine siskin into a poem entitled "Backing Down," I consulted a birdwatcher friend to come up with the "wheezy buzz" I heard that afternoon out in the forest when I sensed a bear was nearby.

Just two or three weeks ago I taught Terry Tempest Williams's Refuge in a graduate literature class focused on regional memoir. Myriad birds of the Great Salt Lake and of the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge fluttered and flapped on nearly every page. My least favorite bird moment from that book: Williams lies down beside a dead whistling swan "imagining the great white bird in flight." Although I found this adaptation of Leda and the swan arresting, it was, as Huckleberry Finn might have put it, "too many for me." My most favorite bird moment: Williams's comments on the aggressive starlings and the subsequent attack of a peregrine falcon that diminishes the flock by one. Whether that scene happened exactly as reported was not of great moment to me, although we spent considerable time throughout the term discussing the limits of "creative nonfiction," and we agreed that the falcon was terribly convenient. Williams writes, "Perhaps we project on to starlings that which we deplore in ourselves: our numbers, our aggression, our greed, and our

cruelty. Like starlings, we are taking over the world."

For the record, I polled the dozen students (anonymously) in that class, about equally divided between men and women, and found that the most popular memoirs were Mark Spragg's Where Rivers Change Direction and Kim Barnes's In the Wilderness. The positive vote may have been weighted somewhat in Barnes's favor, as she teaches at the University of Idaho and several students in the class took or were taking a course or courses from her. Williams's Refuge was neither among the most nor least popular of the nine books we read. A few students complained of the amorphous nature of Refuge: part environmental or ecological commentary, part family memoir, with focus on Latter-Day Saints (Mormon) patriarchal culture, part political outcry against the high rate of cancer in Utah and its connection with nuclear testing. Other students liked the book because it was "all over the place."

It was just before we started on Refuge that I accompanied my fantasy football pals on our annual elk hunt outside Weippe (pronounced wee-ipe), about a hundred miles to the east, in the Clearwater National Forest. That is, they hunt elk and deer, while I go off by myself to walk grouse trails. They usually encounter grouse while setting themselves up for deer or elk, but they rarely shoot at them, preferring to wait for big game. Generally, two or three of the half dozen or so who hunt for deer or elk manage to bag something, usually a deer, and I invariably drop a grouse or two. This year, a couple of days after the opening, my friends invited me to accompany them to a tree farm where they had seen a large flock of grouse and several deer as well. Their notion was that they would set themselves up a couple of hundred yards to my left and right, covering the extreme flanks of the area, and I would give them some time to get ahead of me before parading down the center of the farm with my shotgun, blazing away at the birds and scaring the deer toward them.

Although this plan of attack now strikes me as something between dangerous and foolhardy, it seemed quite sensible at the time. I plowed ahead, but as I marched down the center, I kept noticing first the guy on my left and then the guy on my right angling toward me. While the effective range of a shotgun is no more than 60 or 80 feet and #6 birdshot at that distance is not likely to be fatal to a human, the high-powered rifles my companions were toting are another matter. They were made to drop a sizable animal, humans included, at about a mile. I stopped and angled away, stopped and angled away again. Eventually, just as the tree farm ended at a barbed wire fence, I jumped the flock of grouse. Or maybe they jumped me. At any rate, I scored no hits and my pals saw no deer. We split up again and made our way back through the tree farm, this time observing healthier latitudes from each other. I blundered into the flock once again, perhaps twenty birds, but they were wise to me.

The three of us met at the road from which we'd set off and headed for the truck. It was getting cold and the light was fading. A little wind picked up. In the gray sky we saw large black birds flapping in derision and cawing mockeries at our failure. Of course this sort of personification is about what you'd expect of poets and English professors, but Jeff is a landscaper and rock musician, so he found our anthropomorphisms comical. It was Jeff who requested that if I were to happen upon any crows, he would appreciate it if I'd bag one for a good friend of his in California. He wanted to have a specimen stuffed for display, but it was against the law to shoot crows in that state. In Idaho it is legal to shoot darned near anything. Witness, for example, the slap-on-the-wrist conviction of "voluntary manslaughter" for Claude Dallas back in 1982 after he killed two game wardens in what some folks would call "cold blood." Many Idahoans considered him a folk hero. In Idaho one might shoot a crow with impunity.

So the three of us were thinking crows when several large black birds cawed overhead, and I decided to retrieve some measure of my self-respect, having failed dismally with the grouse, by dropping one of them. I raised my new Winchester 12-gauge pump-action and fired. One of the birds doubled up and let out a "caw-caw-caw" as it angled away from us. I pumped in another load and fired again. This time the bird stopped mid-air as if it had hit an invisible wall, and it plummeted, hitting with a surprisingly loud thump just a few feet away. My buddies congratulated me on my fine shooting. Words like "sharpshooter," "deadeye," and "birdslayer" (as opposed to Cooper's more renowned "Deerslayer") were mentioned. I felt an elation akin to what I'd experienced almost fifty years earlier when I shot that mockingbird with my air rifle, only this was better because I had an admiring audience.

We stood over the huge black bird with something that might have been awe. Its beak was large and heavy, and its talons were enormous. It looked menacing. But it was quite dead. Often when you shoot a grouse it will whip itself into a crazy, feather-spinning death-dance. Even if you happen to shoot its head off, it will flap around maniacally for a matter of minutes. Those who have chopped off the heads of chickens, as our mothers would have done pretty much on a weekly basis seventy or so years ago, will have experienced this phenomenon. But this great black bird was ominously motionless, and we repeated to each other our versions of how it had fallen and how heavily it had struck the earth.

"Caw-caw-caw," Rick said, "Mayday, mayday!"

"Eeeoooorrrr… boom!" I said, imitating movie versions of Zeroes and Messerschmitts shot down by daring American aces.

"Bad news," Jeff said. "This isn't a crow. I'm afraid it's a raven."

"Shit."

"Are you sure?"

"Ravens are illegal as all hell."

Well, of course none of us was certain. After all, if we'd really known what we were doing, we (I say "we," but of course only I pulled the trigger) wouldn't have shot the bird in the first place. By consensus we decided to leave the bird where it lay. Jeff wanted no part of it. "Leave it for the coyotes," Rick said. Well, of course, sure, that's what we'd do all right. Something tightened inside me, and I felt the kind of guilt only a poet or an English professor, haunted by all the birds of literature, can feel. I felt sick with foreboding. Who knows what misfortune and ill luck might befall our hunt? Should I bother going out after grouse the next morning as I'd planned? I imagined myself somehow stumbling over my shotgun and blowing my damned fool head off. I recalled the passage early in Williams's Refuge, which I would soon be teaching again, when she comes across the stereotypical rednecks in their blue pickup while looking for endangered burrowing owls. She describes these members of the Canadian Goose Gun Club as "beergut-over-beltbuckled men," and I was beginning to feel myself a member of their shameful club. I could imagine Terry Tempest Williams flipping me off.

On the way to my truck Rick proposed going back for the body of the raven and hanging it around my neck as in Coleridge's "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner," a poem I had taught within the past year, and an old favorite. "Quoth the raven," said Jeff, "'Nevermore!'" That was coming. I knew Poe was coming, and I'd expected the reference to Coleridge, too. I had it coming.

"He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things both great and small;

For the dear God who loveth us,

He made and loveth all."

So said Rick, having memorized the exactly apposite passage, that noisome bit of moralizing Coleridge pasted onto the end of the poem in order to quell complaints to the effect that his poem was not sufficiently edifying.

Maybe we literary types suffer more than others when it comes to this sort of thing, and the more you've read and thought about, the more you suffer. I'm a big fan of the late James Welch's epic novel of the Blackfeet, Fools Crow. In fact, I wrote a book on Welch a few years ago, so I've reflected on that novel more than the typical reader might be supposed to have done. The young brave who is to become a medicine man for his people undergoes several mystical or visionary experiences in the novel, and in one episode, which I heard Jim read before the novel was published in 1986, White Man's Dog, as Fools Crow is then called, carries on a lengthy spirit-conversation with Raven. The bird leads the Indian to a trapped wolverine, which he adopts as his spirit animal. My encounter with the raven was not so liberating or so empowering.

When I got home the next evening, I hunted up my wife's copy of Peterson's bird book and looked up crows and ravens. The squared-off tail feathers confirmed my guilt.

One time during the mid-1970s I was driving with my family back from a vacation in Florida, and I decided to hop off the interstate and take the scenic route through central Montana. I was gambling that old US 12 was such a route. It would take us along the Musselshell River, past tiny towns with exotic names like Sumatra and classically western names like Roundup. I don't believe we made it to White Sulphur Springs, Ivan Doig country, because of the birds. We'd gotten a fairly early start, gassed up, talked with the attendant who agreed that yes, maybe US 12 would be more scenic than I-94, at any rate, and the road was good enough, and there wouldn't be much traffic. He did not mention the birds. Alfred Hitchcock's birds were homicidal; these central Montana birds were suicidal. To this day I have no idea as to their species: small, drab birds flipping up from the roadside and throwing their feathered bodies against the car. They struck with small, pathetic thumps, usually against the windshield, again and again. With each feathery whump, my wife flinched, or I flinched, or we both did. Our daughters, probably about ten and five at the time, were blissfully unaware. What was it that drove these anonymous birds to their deaths? Were they heavy with dew? Perhaps they were drunk on some wild berry. We never learned what it was, but I'll bet we took out at least a dozen little nondescript birds, better than I've done on my best day hunting dove or ducks. As I recall, US 12 was not all that scenic, either.

In a lifetime of hunting birds, certain moments fix themselves in memory. That morning it took me two boxes of shells to bag my limit of ducks on Chatcolet. That morning on Coyote Grade when we took poet John Haines hunting with us, and I hit a cock pheasant that soared straight up toward the sun, then suddenly fell like Icarus. The winter afternoon we drove through the wheat fields of the Palouse with writer Jim Heynen looking for partridge outlined against the snow, and how he would leap from the car, shotgun in hand, and blast away at them, bagging two or three at a shot, his technique mastered from a boyhood of shooting on his family's farm in Iowa. The pheasant I dropped north of town near the Palouse River, finding it at last splayed against the stream bank in such a bright show of color that I almost regretted having shot it and felt when I came upon it that I must be in the grip of some perverse joy at having killed beauty itself. Ben Jonson wrote a little epitaph on a woman that includes these lines that actually came to mind at the moment I found the bird: "Underneath this stone doth lie / As much beauty as could die." Poetry may as easily plague us as soothe us.

Over the years, I tell myself, I have not killed birds wantonly. With the few exceptions noted above, I have eaten what I shot, and like most hunters, I like to believe that makes it okay. I have not grown up to become a merciless man, I tell myself. But perhaps it is true that I lack compassion. The day after I shot the raven I bagged my limit of grouse, and Jeff shot a nice buck two days later. The spirit of Raven did not punish us. Nevertheless, I do regret having shot that raven, and that mockingbird as well.