Winter 2003, Volume 20.2

Art

Susan Makov

Dreaming in Layers

Susan Makov (B.F.A., Syracuse University, M.F.A., SUNY at Buffalo) is Professor of Art at Weber Sate University, where she teaches printmaking and studio art. An award winning artist, her work appears in numerous collections including the Museum of the American Indian, New York City and the Southwest Museum, Los Angeles. She has exhibited at places as varied as the Bradford City Art Gallery, Yorkshire, England; Chicago Center for Contemporary Photography; and the Ucross Foundation, Wyoming. Along with her husband, Patrick Eddington, she wrote and illustrated the highly acclaimed Trading Post Guidebook: Where to Find the Trading Posts, Galleries, Auctions, Artists, and Museums of the Four Corners Region. Susan is affiliated with the Phillips Gallery, Salt Lake City and Robert F. Nichols, Sante Fe. She lives in Salt Lake City with her husband and two cats.

I am an artist who makes books, photographs, and prints, and finds herself in the West after having been raised in a suburban New York neighborhood of Hicksville. I have now lived and taught in Utah for half of my life. I knew I would end up in Utah when in graduate school at SUNY Buffalo I began to make images of cactuses.

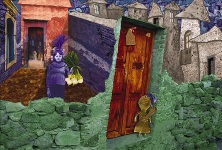

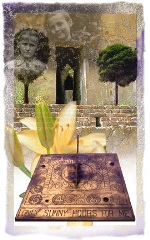

The imagery that comes to me has its origin in my dreams. In my dream world, I have tried to link the suburban youngster whose most adventurous outing was a bicycle ride to the chicken farm two blocks away from my house to the adult who has traveled through European worlds, still lost in time, and ended up exploring the Southwest worlds of Native American Pueblos and the 19th century realms of the trading post.

I am not the person of the suburbs anymore, yet my familial links go back to the great waves of immigration and the struggles of a maid working in the lower East side of New York City. Her family of eleven brothers and sisters remained in Russia. The stories that came down through various relatives were always intriguing and, I suppose, mostly true. Such as it is with family mythology, and now my own myths take on familial lives of the past and present. Dreams are one's residence in a new world, as many immigrants discover, and my choice to stay in this new arena of the West plays out its nightly version of deciding who I am in the context of great mountains, deserts, and vast spaces, speckled with small enclaves of distinctly different family groups.

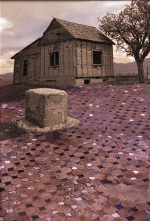

My artwork draws upon photographic documents of this western world and, as it occurs in many dreams, mixes with often jarring reoccurrences of aspects from daily life and past events. As an artist working with the new technology of the digital world, I find that I am able to combine everything that I have learned about art, drawing, photography, printmaking, and other media to work with this fluid digital world.

In the worlds of my parents and grandparents I travel back in time to a re-invented world where my grandmother still grows red onions in her backyard on Coney Island—she uses them as a dye for her Russian Easter eggs. Her "garden," as I can only refer to it, consists of a small triangle of land tucked behind the three story brownstone where she and my grandfather live in the basement. It is my world as an eight-year-old on summer vacation, and it's an occasional destination of my nightly wanderings.

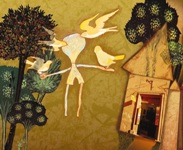

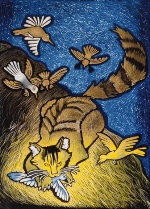

My mother's world in suburbia consists mainly of the front and backyard gardens where she reigns, not always supreme, over the local squirrels that knock on the front door for peanuts and the increasingly wild backyard that attracts birds to it. Their nests are, infrequently, my mother's blond bouffant hairdo. I know that it was my mother's odd relationship to animals and nature that I must have brought west with me.

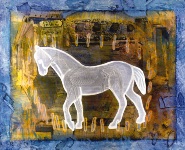

Her unusual relationship to nature influenced the anthropomorphic focus that both my husband and I have on the world around us, from the mythology of our individual pet cats who reign over our house as clowns and sages to a more general population of animals whose struggles with the world (theirs and ours) seems to be ever increasing as time goes by. Old photographs of the many storied piles of buffalo bones on the western plains from an exhibition at the Cody Museum in Wyoming remained in the back of my mind for several years before their appearance in my work as ghost buffalos leaping over a number counter with a vast plain in the background. The empty space of my dreams is animated by buffalo moving, jumping over a river running through some vast savannah of Africa or Asia where disruptive human encroachment is playing its role with the animal populations. This is not a comforting dream, and the animal number counter continues with great speed. Coptic jars become the residence of the animals' souls.

Where are the frogs or alligators whose numbers were once evident but who now find themselves as objects of an unusual news story—but never part of our real lives? Today, nature is corralled and harnessed and inspected.

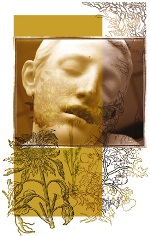

At times the medical world plays a part of my mythic creations. I try to understand the process of aging and the scientific inspection of my body. Many times the investigation of the workings of my human system becomes a monument to scientific exploration and discovery rather than simply an attempt to ease pain or answer a question about my own latest incarnation upon another year passing.

The great thing about making up a mythology about your own life is that it can have many happy endings. After all is said and done, my teachers are my cats. My male Siamese, Rembrandt, has a very solid world view: he sleeps undisturbed, knowing the appropriate times for all life's varied activities. As a tiny kitten, the size of a handful of dirt, he fought ferociously for the food that was presented to him, even though he was surrounded by adult cats ten times his size. We got him as such a young animal that nothing bad had ever happened to him. He still believes in this way of looking at the world. I prefer to use his world mythology whenever I can.