Spring/Summer 2008, Volume 24.3

Essay

Adolph Yonkee

A Brief History of Lake Bonneville

All is flux, nothing stands still

—Heraclitus of Ephesus (ca 500 BC)

As children, it is easy to accommodate the idea of Lake Bonneville. The Provo Shoreline looks like a huge bathtub ring around the Salt Lake Valley. It is a bench I know well, because we lived on it…. We would sit on the benches of this ancient lake,... look west to Great Salt Lake and imagine.

— Terry Tempest Williams, Refuge (1991)

Adolph Yonkee was born in Thermopolis, Wyoming, an ideal playground for a young mind interested in geology. At age three, Adolph was already an avid rock hound, searching for agates across sagebrush covered hills. As the rock collections grew, he went to the University of Wyoming to receive a Bachelor of Science in Geology, and to the University of Utah to earn a PhD, studying how mountain systems form. After working for the Utah Geological Survey, Adolph started teaching at Weber State University, where he has shared his joy of geology with students for the past 16 years. He still searches the sagebrush hills for clues of Earth’s vast history, chasing his childhood dreams.

View to the northwest of Antelope Island, the largest island in Great Salt Lake. Frary Peak is the high point. Shoreline benches carved during the rise and fall of Lake Bonneville recall the story of past landscapes. Shorelines labeled on left side of photo are: B - Bonneville carved about 17,000 years ago when lake was over 1,000 feet deep; P - Provo carved about 15,000 years ago; and G - Gilbert carved about 12,000 years ago. Photograph from Utah Geological Survey taken in 1988.

The time to sculpt a landscape, the time to text a message. How are we to understand the rhythm of the natural world, when we live such a short and harried existence? Earth’s history is all around us, but requires patience, a clever eye, and imagination to discern. The landscape we view today is ephemeral, being but one page in an unfolding story. Yet, this landscape also holds clues to the past, recording the metamorphosis from ancient to modern worlds. Preserved amid the rocky slopes of the Wasatch Range and across the expanses of the Bonneville Salt Flats are vestiges of an ancient lake that inundated much of northwestern Utah more than 15,000 years ago. For a moment, forget the cacophony of today and journey through time to hear the story of Lake Bonneville.

Imagine the scene before you. It is summer, about 30,000 years ago, yet snow fields cling to the mountain slopes, for time has receded to the last ice age. Earth’s orbital dance around the sun has changed, bringing shorter summers and brutal winters. Lake Bonneville has started to rise, sparkling in the cool, thin sunlight. In other parts of the world, Neanderthals hunt on frozen steppes, while Cro-Magnon paint pictures deep in the caves of Lascaux in France. Extremes require action, stimulate adaptation and bring death. No humans roam here, though; you are alone, in isolated silence.

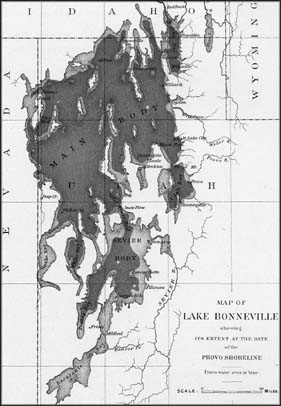

Map of Lake Bonneville by G. K. Gilbert (1890). Gilbert conducted extensive geologic studies, finding evidence of past shorelines of an ancient lake. The dark grey outline corresponds to the shoreline at the Provo level. The light grey outline indicates the maximum extent of the lake at the Bonneville level. About 17,000 years ago the lake extended from southernmost Idaho across much of northwest to central Utah and into eastern Nevada.

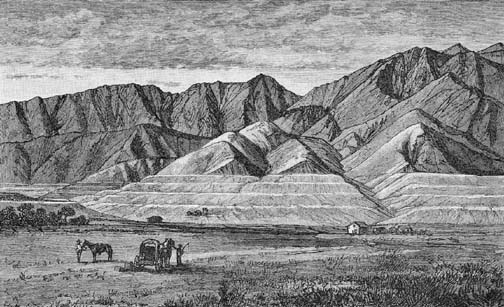

The years come and seasons pass, the lake freezes, then thaws and swells with melt waters, as glaciers grow across the mountain slopes. By 17,000 years ago, Lake Bonneville stretches beyond sight, dammed partly by a landslide at its outlet far to the north, drowning the desert to the west beneath a thousand feet of water. Only a few islands (the tops of mostly submerged mountain ranges) rise above this surreal inland sea. Storm waves crash on rocky beaches carving the Bonneville shoreline, the remains of which will provide future geologists with a mirror to view the distant past. Wooly mammoths graze on windswept grasses, and saber-toothed cats dine on prey; bones of the dead are buried to become fossils. A few hardy trees dot the lower slopes near the lake, shrinking upwards to krumholtz, then tundra above. Beneath the waves, trout swim in fresh waters, while deep below layers of mud settle to the bottom. Each year the rivers bring more water, along with their loads of sand and mud, as glaciers slowly grind away the mountains. But the mountains are restless, as tectonic forces stretch Earth’s crust, creating earthquakes that suddenly lift the mountains a few feet and drop the valleys a few feet more, adding room for the growing lake. It was these same forces, which for 10 million years uplifted the ranges and down-dropped the valleys, step by seismic step, to form the Great Basin, a chaotic land where rivers drain, never to reach the ocean.

Levels of Lake Bonneville and Great Salt Lake. The lake started rising about 30,000 years ago, and reached its apex 17,000 years ago as the Bonneville shoreline was carved. The lake rapidly fell to the Provo level, then to the Gilbert level, and finally to the remnant Great Salt Lake as the climate warmed. Inset shows historic record from 1845 (while Fremont was exploring the area), to 2005 (when over one million people live near the lake shores), during which time the lake elevation fluctuated between 4192 and 4212 feet.

The basin, however, is not growing fast enough for the sprawling lake, which now covers an area of 20,000 square miles. Suddenly, the dam fails at the north outlet. A thunderous outpouring of water, larger than the Amazon, surges northward, toward what is today the Snake River, and ultimately to the Pacific Ocean. The turbulent torrent carries boulders the size of houses and carves huge channels, which will later baffle geologists studying the desert west. Standing on the previous shoreline, you watch the lake lower by more than 300 feet over the course of days. What had once been submerged along the lake’s edges is again exposed to sun, wind, and rain. Mud and sand are washed away from the newly exposed land, carried by streams and rivers to form expanding deltas into the lowered lake, erasing older layers while adding new pages to the story.

Soon, the outlet has eroded down to a bedrock ledge, forming a sturdy dam stemming the debouching of the lake. Centuries pass. The time is 15,000 years ago, but the ice age continues; glaciers still envelop the mountain peaks. Rivers continue to feed the lake, which extends far to the west, dotted by islands. Waves break along new beaches, cutting the Provo shoreline. Night comes, a cool breeze stirs, the full moon rises across the immense but slowly changing landscape.

By 12,000 years ago, Earth’s climate has warmed as its orbital dance around the sun subtly shifts. The summers grow longer, the winters less severe. Glaciers retreat to shadowy cirques beneath the highest peaks, and then are gone. Inflowing rivers shrink and the lake evaporates more each summer. The shoreline recedes westward and new islands emerge. The outlet is now dry and the lake is becoming salty; the trout are dying. The wooly mammoths disappear, while lowland deserts return and forests retreat to higher and higher elevations. The lake has one final gasp, carving a shoreline, which will be later named after scientist Grove Karl Gilbert. Soon Lake Bonneville will largely dry up, leaving a briny remnant, Great Salt Lake, scarcely 20 feet deep at its center. Humans have migrated into western North America; a new voice has joined our story.

It is summer 1843, and Captain John Charles Fremont, who would later fend off Abraham Lincoln to become the first Republican presidential candidate in 1856, rides a horse around the shores of Great Salt Lake and across the deserts of northwest Utah. The captain notices shorelines far above the salt flats and imagines that an ancient lake once covered the region. Thirty years later, a young Gilbert systematically studies the layers of mud and sand deposited along the ancient lake bottom, discovers the deltas that formed where rivers emptied into the lake, and measures the elevations of shorelines that were cut as the lake rose and then fell. He names this ancient inland sea "Lake Bonneville," after French-born army officer and early explorer of the American West, Benjamin Louis Eulalie de Bonneville. Gilbert’s careful measurements surprisingly show that the elevation of the highest shoreline increases from about 5100 feet at the old northern outlet to 5300 feet near the Lakeside Mountains. Today, the Lakesides are a desolate range that rises above the salt flats, but 15,000 years ago the range formed but a small island in the center of Lake Bonneville, most of its slopes bathed in water 1000 feet deep. Gilbert imagines and understands; the weight of the ancient lake waters (totaling more than 10 trillion tons) had bent Earth’s crust downward. As the lake subsequently receded, the crust, freed of its watery mantle, rebounded, rising 200 feet in what had been the center of this once great inland sea. In 1890, Gilbert describes his findings in a quintessential scientific paper, the first monograph published by the recently founded U.S. Geological Survey. In the words of Jack Oviatt, preeminent expert on Lake Bonneville, "the [Gilbert] monograph is comprehensive, but more importantly it is a clear expression of Gilbert’s view of the nature of scientific inquiry—that explanatory hypotheses come from analogies and that multiple hypotheses should be tested and rejected or accepted based on available observations.... If we follow his example, we find that the most valuable and enduring legacy of Gilbert’s Lake Bonneville work is not that he ‘got it all right,’ but that he showed us how to ask the right questions and search for meaningful answers."

Fast forward to 2008. The Great Salt Lake lies paradoxically within the Great Basin desert, where the summer sun desiccates the surrounding salt flats, where water from incoming rivers brings life in abundance along the shores. More than a million people live near the lake’s eastern shores, yet this briny legacy of Lake Bonneville remains largely unknown to most of the nearby inhabitants. Other than the occasional "lake-effect" snowstorm, what do we know of this odd neighbor? Sail across the waters at sunset and watch the avocets feed on brine shrimp, or climb to the top of Antelope Island and gaze toward the skyline, and discover.

Geologists are fond of saying, "the only thing constant is change." Great Salt Lake (and its ice-age predecessor, Lake Bonneville) exemplifies this adage over the course of years and millennia. A few wet winters and the lake swelled to its historic high of 4212 feet in 1987, threatening roads and homes. By 2005, a drought had lowered the lake level to 4196 feet, endangering the brine shrimp industry. What will happen in 100 years, as global warming brings more extreme summers: will Great Salt Lake vanish into the air? What will transpire in 10,000 years, when shifts in Earth’s orbit portend the next ice age: will Lake Bonneville return?

The story of Lake Bonneville and Great Salt Lake is part of a much deeper and richer history that spans, not thousands, but millions of years, for this is not the first nor the last chapter in an unfolding story. Listening to the past helps us understand Earth and our relation to this magnificent home. When we fail to appreciate the nature of time and space, and instead only view Earth as a source of instant wealth to be controlled, we become out of balance with our home. Take time to listen to Earth’s story, take time to reflect on our own (in)significance.

Field sketch, by G. K. Gilbert or an artist of his research party, of shorelines carved by ancient Lake Bonneville along the slopes of the Wasatch Range.

I want to acknowledge the help of Dr. Rick Ford (Weber State U) and Dr. Jack Oviatt (Kansas State U) in providing key insights and suggestions, and in stimulating my interest in Lake Bonneville. I also wish to thank Grant Willis (Utah Geological Survey) for his suggestions and help with the figures.