Spring/Summer 2007, Volume 23.3

Fiction

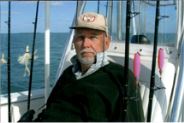

Robert H. Smith

Drive

Robert H. Smith graduated from the U. S. Naval Academy in 1946. He served as a naval officer and retired as a Captain. Following his Navy life, he worked in the fields of operations research and military analyses, and is one of the nation’s foremost authorities in underseas warfare. He has written extensively on defense and foreign policy matters, contributing to the Naval Institute Proceedings, Washington Star, Los Angeles Times, Chicago Sun-Times, National Review and other newspapers and periodicals. On four occasions he has been awarded the Prize in the U. S. Naval Institute’s annual essay contest. In recent years, he has dedicated himself to his first love, which is fiction.

The expensive automobile’s progress was a noiseless hum along the concrete of Route 95 as it rolled through the wooded hills of Eastern Connecticut. The hood reflected the pale blue of the winter sky and patches of slate grey clouds. Traffic was light this mid-week day and the man’s large but pampered hands did not once have to tighten on the leather sheathed steering wheel. He could take pleasure in the hills that rose and fell like swells of some giant and immemorial sea, enjoy the detail of the ice, frozen waterfalls of it, that seeped and clung from the grey faces of billion years old granite through which the builders had cut and blasted this highway. Occasionally his wife would point out one of these frozen falls of ice, either for its impressive mass or a special grace to its beauty. And he would make a reply like: "It’s really something, isn’t it?"

"Amazing." Wanting a better word. A woman who took pleasure in the natural world, absorbed fanciful figures from clouds. She drew her lustrous fur more closely around her neck, the sleek hairs stiff and soft at the same time, tickling her throat.

"Imagine," she mused, "driving all this way from Greenwich. Just for a luncheon."

"Oh, I don’t know. In Texas people zip a hundred and fifty miles down some freeway just to meet old friends for cocktails and dinner."

"They don’t!"

"Matter of fact, once I drove with some people all the way from Fort Worth to Austin and back to have a bite."

"But that was different. That was business."

"True." That it had been, business.

She said nothing for several minutes. Almost timidly, it seemed, she asked: "We could have been Texans too, couldn’t we?"

"Just as well," he said, reflecting that, good as he was at what he did, he could have found fortune just as well far away. Perhaps it was only the unaccustomed length of the drive, but he was restless. He pressed his foot down, savoring the car’s silken acceleration.

"Dear, aren’t you going a little fast?"

"I guess I am," he said, slowing. At that moment he saw the route sign with the remembered name. Surprised because there hadn’t been a sign before; the particular little town too obscure to be entitled to alertment that it was coming up. Yet all at once knowing that he was going to take this turn-off.

"I thought you’d be taking the North Stonington exit," she said as he flipped on his turn indicator.

"A number of these roads will do the trick, actually," he said, easing right .

"I keep forgetting, you know this area up here well. Wasn’t your first college, that funny little junior one, up this way?" She wrinkled her brow, "and didn’t you have some sort of part-time job or something?"

"Or something," he replied, covering a yawn. They were traveling now a narrower road that wound mostly through woodlands and past the small stony farms of New England. After a few miles they entered the town, its beginnings marked by a weathered sign announcing the date of its founding and its seemingly changeless population. Store fronts were set in plain weathered brick buildings with the dates of their erection molded in their cornices.

"These old place names," she said wonderingly, pronouncing this particular one; not badly for someone who had never heard its awkward arrangements of consonants spoken. "I guess they’re Indian."

"That they are. A long time though, I’d say, since any Indians have been seen around here."

She laughed with pleasant exasperation. "Well, hardly." At a stop light, the only one, he saw the sign for his old college. Remembering the little stationery and art supply store on the corner. Hardly more than a cubby-hole of a shop. Evidently still in business though.

"Isn’t that the sign to your old school? Shall we take a look?"

"I think we can let it pass without loss," he said. "It was not exactly memorable architecturally." He added drily, "Nor academically."

"You notice many changes?" she asked.

"More things the same than otherwise." The business section ended at a white spired church set in the midst of broad grassy lawn that was green in spite of winter. Grey tombstones slouched in random attitudes. The main street swung around the church grounds and became a wider street lined with large trees that in summer kept a row of fine old homes in dark and pleasing shade.

"You know," she said, turning towards him as far as the restraint of her safety belt would permit, "I really ought to know more about your early life."

"Not a lot worth knowing."

"And I could tell you more about me. Before we met and so on. Wouldn’t that be a fair trade?"

"Fair enough. But is there a point?"

"Maybe not a whole lot. On the other hand, you may think I have no stories of my own."

The town was behind them and the road had regained woodland and farm. "I don’t doubt you have your stories. Why wouldn’t you? You were a popular girl."

"Well," she laughed easily, "I’m not alluding to anything earthy, or even dramatically romantic. But still…."

For a moment he relaxed with the thought that he need not make the next turnoff. It was not foreordained. But then he was taking it, almost unconsciously, the big car swinging around with a life of its own.

"I guess I would merely note that it’s none of my business, what you were up to before we met."

"Of course it isn’t. Strictly speaking." She made a little gesture, fortunately rare, that he had always found annoyingly fussy. "At the same time there’s no reason to… retreat from the things that made us. We’ve shared everything. Should there be still, by this time, some part of us that is stranger to one another?"

"Hardly strangers," he murmured, adding a pet name. At the same time making a vow, possibly unenforceable, concerning avoidance of these long drives in the future. The woods were all around them and the winter sunlight, pale and yellow, slanted by the bare limbs, lit the tall grey trunks of pristine forest with a spare and tender beauty. He smiled to himself at the wryness of a lost opportunity. This broad and fine wilderness of northeastern Connecticut, its unspoiled emptiness, had been a secret well kept. The secret was out and everyone was buying up wide uncrowded tracts, people with money from as far away as New York and Boston. Its emptiness, its lonely lakes and ponds with their undisturbed herons and deer that came down at twilight to drink, was passing. The friend they were on their way to visit for luncheon was one of many who had seen the future earlier than most and who had scooped up thousands of forested acres for a song.

She turned towards him, drawing her legs up under her comfortably on the silver grey plush of the car’s leather, and smiled puckishly. "What’s wrong with going back to the past a little? You’re always resisting it. I like to remember my past."

"Your past was a bonnier one than mine. You were never poor."

"That is true. Even so, what’s to be so solemn about? Admit it. When you were going to school up this way you must have had a girl friend." She gave him a dig. "Knowing you, a couple."

"I guess."

"You know. And you remember their names too, I’ll bet."

In fact there had only been one, and he remembered much more than her name. Green eyes and bones fine and tough as a hawk’s. Pale skin that never knew the time for makeup. And interesting teeth, in rare but glowing smiles, that told of a childhood that had never heard of cosmetic orthodonture. Sinewy hands, equally skilled at kneading a sculptor’s clay or wringing a chicken’s neck. A life lived in paint streaked jeans and with dust under her nails, wisps of her artistic creations sometimes clinging heedlessly to her eyebrows, poignant in their unconscious whimsicality. A life of such fiercely focussed desire as he had not imagined before. Nor known since. A life too, shared for the time it was, that he recalled mostly for its harsh edge. Her need for cash unrelenting, where anything that happened, a balky furnace, even a flat tire, could never be mere incident but seemingly must graze disaster. She was older than he, had come to her vocation late. Perhaps for that reason, the fact that her time to make it was going to be shorter, the ascent steeper, the impatient boil of her passion was that much the greater. It was all so obvious now. Everything that had happened explicable, fated in their circumstances. He was nodding to himself with belated understanding, when suddenly familiar scenes were all around.

Not that he was surprised. Scientific education had taught him that the untouched workings of geologic time did not alter the face of earth by so much as a millimeter in a man’s lifetime. Thus over there was the same bare clump of grey rock out of prehistory, now right here close aboard the remembered great oak still standing by the road, And, as if it were yesterday, he knew that around the next curve would be the final turn-off. He slowed to negotiate its sharpness.

She frowned, curiously but good humoredly. "You’re sure this funny little road is the right one?"

"Pretty sure," he said. Cars had gotten larger over time though and its bulk filled the lane which fell off sharply on either side into water filled drainage ditches. He bridged the tiny remembered stream, ice-edged now, which foretold the cottage coming into view. The car lurched heavily in and out of potholes.

"Goodness," she said in the aftermath of one that jolted the big car right down to its shock absorbers. "This can’t be right. You’ve taken a wrong turn!"

"Afraid I may have at that." Then around one more bend and there it was. Sitting at the end of a rutted driveway a hundred feet away. The mail box by the side of the road still cockeyed. A FOR SALE sign, rusting and lopsided, stood in front of the little dwelling with its torn screens and curtainless windows and flaking white paint faded to greyness. He pictured her coming out the front door, letting the screen door slam, trotting down to the mail box, anxious each day for news… for word of reviews, a possible sale, of another meager commission, maybe a show to come, above all, approval. It wasn’t vanity; it was survival, money, or the promise of it, to enable her to go on. There had been a FOR SALE sign up even then. Something else to bedevil her days. The fear that the place might suddenly be sold out from under her, taking away her studio, its space and precious light, all her materials and brute equipment and unfinished stuff that could not handily be moved.

He had halted the car by the mailbox. Rather it was as if it had stopped itself. Just sitting there, purring away.

"Well," she said, "aren’t you going to turn around?"

"I suppose I’d better."

"You suppose?" She waited. Then had waited long enough.

"Why, just pull up. Obviously nobody’s living there. We can even drop in. Take a look. You’ve always been smitten with this area. A fixer upper. Isn’t that what the real estate people would call it?"

"That they would." Reflecting that she was not one of those persons able to be archly funny. Facetiousness unintentionally falling off into sarcasm. But that wasn’t why his grip on the wheel had tightened. He was recalling their last day. Seeing her standing fixedly on the same sagging steps, no longer shouting, merely looking stunned. Drawn, all tight gone out of her. They had awakened to a raw grey morning on which she discovered first off—her shouted curse from out back was a cry of pain—that a fox had killed all three of her laying chickens. Then the wood was too wet because he hadn’t carried any in the night before, and the stove kept smoking and not for a while was there even to be coffee to start the day. Last straw had been her old pickup refusing to start, a morning when it was needed more than most, his exams scheduled that day and art supplies at the rail depot in town waiting for her to claim. Sitting side by side on the ratty leatherette seats, listening to the engine’s mournful grinding away into silence, she had lashed out at him. The battle went on most of that morning, moving from kitchen to studio, all the while fresh problems and old frustrations continuing to cascade over the strained circumstances of two marginal lives rubbed raw. She didn’t give a damn about him he remembered shouting at her. Wanting him around only for the pitiful little extra cash he was able to contribute, taking advantage of his young man’s muscles, a handy splitter of firewood…. He had stormed into their shared room, the more pathetic for its small reaches towards horniness, and tossed into one suitcase all he possessed worth taking in the world. Then grabbing up his textbooks he had headed down the lane to the main road and on to exams that fortunately he was able to reschedule.

"Gittalong," she said, startling him. A silly little phrase, but long familiar, one of those with her from girlhood. "You’re just sitting here, old boy. We’re not stuck, are we?"

"No," slowly coming out of it, "we’re okay." He felt the acuteness of her sudden quietness.

"Are you all right?"

"Fine."

"Because I saw your lips moving."

"Did you now?" He smiled sheepishly, he hoped disarmingly. "Another sign of age," he murmured, getting the car lumbering forward onto brown and weedy grass that passed for a lawn. He felt the wheels sink into the spongy ground but with care he was able to work the car around. A few minutes later they were out of this darkling enclave and back on the main road, passing the comer where he remembered bumming a last ride from a farmer chugging by on his tractor. As he took in again the liberation of the open road, out in the sunlight, he realized that he must have been wanting to leave her. Her future he could see, but not his own. Her talent was possibly large, maybe even great—her art was all a mystery to him—but he realized even then that he had no talent but for making money. Which is to say no talent at all. Yet because he had been looking for an excuse to break it off, it meant there had been calculation in his actions, and with that realization he felt a return of guilt which had never quite gone away. Yet there had been truth too in some things he had said. For sure, she had been using him. Yet didn’t everyone use everyone else, children using parents, parents children, husbands wives, and the other way around, at some time or another? That went with life’s territory. The thing he regretted most was accusing her of not loving him. Because he knew better. There were nights, very different from the fierceness of her days, and the peace of cold, clear stars glimpsed afterwards through a curtainless window. She had caressed him, holding his most precious parts, speaking words of awe and caring that went beyond, in fact had no part of, lust and its compelling curiosities. In its simple taut eloquence was respect, cleanness, dignity and reverence for human ways, something treasured when much else had been forgotten.

Their road met another freeway, one they would not be on for long but whose sweep and great curves vanquished hill and forest and sped them along its broad and bone grey surface. Hying by good old remembered names, Moosic and others, all memory of Indian tribes extinguished but for these fresh green and white signs. Sailing along in silence. Braced for her inevitable surmise.

"You knew something about that little house where you had us bumbling about, didn’t you?"

"That I did."

"And you had to see it again."

"I found myself… curious."

"Do I take it that was where you lived when you were going to school up here?"

"Yes. Part of the time."

"With a girl?"

"A woman. But yes."

"Whom you were in love with."

He kept his eyes on a straight section of neutral highway. "Yes."

"And whom—you’re in love with still!"

Hundreds of feet of highway more he let reel in under the polished hood. Taking a deep breath.

"Let’s just say that she was someone I let down."

She said something low and coarse, words out of character. She pulled out a tissue and dabbed at her eyes.

"And now," she said, "after all these years I’m discovering that you’ve been living with, well, what? Some sort of secret ardent memory apparently."

"Listen. Please." He spoke softly, but with effort. "It was long ago. You are making too much of this."

"Am I?" She laughed bitterly. "And what a grand time to happen. On our way to a lovely party that I was blissfully taking for granted we were both going to enjoy. Now… I’ve got to think how to handle this."

"Nothing’s happened," he said wearily. "Nothing’s to handle."

"Naturally, too, I have to be assuming that you know where she is, that somehow you’ve even been staying in touch. And God knows what else…."

He shook his head. "Neither hide nor hair."

Which was not entirely true. Because for a while he had tried, in a loose way, to keep track of her. When art magazines came his way he used to scan them, hoping for some tidbit of news or advertisement that might tell how she was doing. Years later, well after he had gone on to a first rate college and graduated, and was by then employed in New York, he encountered mention of her inclusion at a showing at one of the Manhattan galleries. It was too late to attend but he had combed the newspapers for reviews. He found nothing, nor saw anything more afterwards. In a way, though, he remained sure that she was still alive after all these years. Unable to picture that spirit vanquished.

They were almost there. Nearness to their destination was signaled by a change in the landscape, one resculpted by man. Grand pillars and scrolled iron bordered the entrances to little roads sneaking off into private woodland where, high on favored hillsides, homes looked across a countryside of unspoiled loveliness.

"You know," she said, "we could talk about it, not right now I realize, but later on. I might be able to help."

"There’s nothing to be helped." Yet he was struck by the good sense of her words, unexpected right notes, and was not sorry that she kept on in her small but determined voice.

"We both know it hasn’t all been peaches and cream. We’ve had times to weather. I mean, so now… this too—"

"Will pass," he broke in softly. "Sure. Just give it time," he said, and, seeking his own right note, gave her limp hand in its soft leather glove a squeeze.

"I’ll wait. I won’t be a pain. We’ll let it unfold. Let the time be ripe."

"That’s the way, hon."

He was turning off onto a subtly marked private driveway whose windingness and wooded length kept tantalizingly hidden, until the very last, glimpses of the sequestered mansion that was its goal.

"Remember," she said, naming their hosts, "how they always put on such a spectacular spread."

"That they do."

"And I’ll bet we’ll see lots of people we haven’t seen in a long time. And you know what, too? We don’t have to hurry home. We can stop off at some nice inn. There’s no reason to put ourselves through a long drive in the dark, is there?"

"Not a reason in the world." Space was opening ahead, and there was a near vista of elegant brick and handsome cars and several limousines in a soothing cluster in the broad circular driveway. A woman in a long fur and a man in a dark coat were walking up the front steps and he was thinking that he knew them. He observed the uniformed maid’s greeting, the broad smile in a round yellowish brown face, some elusively sensed, but not improbable, spawn of some recent U.S. defeat or shameful betrayal. He imagined her as having made it here across wide and cruel waters. Yet now, observing the stragglers coming up from not too far away, the young woman held the door open and kept her welcoming smile unbroken. Music floated out, and laughter. He pictured a frosty silver punch bowl and floral displays and lively talk and the press of warm hands.

"We are going to have a great time." She moved closer to him. "I know it."

"Why, sure we are." Meaning it. Because this weight would lift, as such weights do on the hearts of the prosperous and the healthy minded. For, oh Lord, had there ever been such a time before, and would there be again, of such ease and treasure let flood upon the world when ordinary people were graced to roam it freely, taking from it pleasure and substance richer and more protecting than kings of old?