Winter 2007, Volume 23.2

Conversation

Melora Wolff

Getting Weathered: A Conversation with Christopher Camuto

Melora Wolff was Philip Roth Resident in Poetry at Bucknell University in 2004. Her recent work appears in The Best American Fantasy 2007, The Southern Review, Green Mountains Review, West Branch, and Fugue. She has served on the Poetry Advisory Board of Weber Studies.

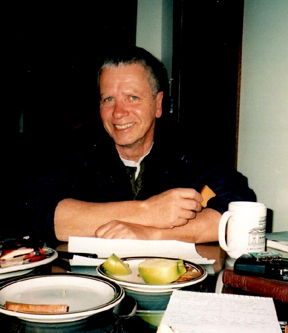

Christopher Camuto is the author of numerous articles and essays, and three books of nonfiction that have established his reputation as a gifted translator of the natural world, a "walker" and witness able to give lyric voice to a landscape’s powerful, elusive spirit. His collection of essays on angling in the Southern Appalachians, A Fly Fisherman’s Blue Ridge, was published in 1990; Another Country: Journeying Toward the Cherokee Mountains (the book he says matters most to him) in 1997; and Hunting From Home: A Year Afield in the Blue Ridge Mountains in 2003. Wherever Chris journeys, he contemplates the deepest relationship between ecologies and words, the sometimes contradictory consciousness of a place and of humanity, seeking the histories, myths, facts, and haunting physical legacies of earth’s designs. He has at all times the eye of a camera, the ear of a poet.

Chris taught for several years at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. In the fall of 2004, he moved to Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, to join the fulltime faculty of Bucknell University where he teaches literature and creative writing, and keeps a welcoming office at The Stadler Center for Poetry, his door adorned with encouraging notes for his students, as well as Thoreau quotations, and a long, comprehensive list of birds he has sighted since his arrival. Chris and I met for the first time at The Stadler Center in 2004, and I traveled back there in the spring of 2005 to speak with him about his writing, his experiences, and about his forthcoming books: Time & Tide in Arcadia: Seasons on Mt. Desert Island (to be published by W.W. Norton in 2007) and In a Landscape: Notes on the Coast of Maine.

Read an essay by Christopher Camuto published in this issue of Weber Studies.

In Another Country and in Hunting from Home, your experiences in the wild and your witnessing of nature become a fierce pursuit of the meaning of language itself, and specifically, of poetic language. The word and the world seem intimately bound together for you on your journeys. How do you experience the relationship between poetic impulse and your immersion in the wild?

I see it in the writing, but I don’t think about it when I do it. Partly, it comes from loving the rhythm of good prose and good poetry. A lot of writers are trying to write to a base rhythm. The rhythm of walking has always struck me as a kind of iambic pentameter, a physical embodiment of our curiosity, and a means by which our minds and bodies are invited to walk together. Landscapes are almost always a calculus of something static and something dynamic, and every good writer chooses his or her own language to deal with that. Today, you and I went to the Montour Preserve, and we looked at what looks like an empty expanse of water; and then, we look more closely and we see some diving ducks, some geese—you’re led into a base line iambic pentameter, which is always working toward abrupt juxtapositions, compressions, other devices that are more common to poetry than to prose. I think paying attention to the simultaneous complexity and unity of anything in nature brings you to that as a writer—if you’re foregrounding the thing that you’re looking at, rather than the motive for the looking.

Most of the writers who have worked in this field I think have weathered like that, worn themselves and their language smooth from all the hours spent watching. I like writers who write in long rhythmic lines. Poets, and prose writers. There’s a promise in that. I don’t write from any theological perspective. I don’t have any theological beliefs. But I think there’s a kind of aesthetic of hopefulness in certain prose and poetic rhythms that substitute for more self-conscious theory of what holds things together—just the rhythms of things, the continuity of things, just the way that nature does work. We can study it scientifically or aesthetically, but it’s shockingly obvious that nature is the example of the thing that works without any effort, of how life works on its own. There’s something reassuring about anything that happens in nature. We were talking earlier about the beginning of spring here in the Susquehanna Valley—it’s in the migrations of tundra swans and snow geese overhead up the river. There’s nothing to be argued about—it happens; it has continuity; it connects the outer banks with the high arctic through central Pennsylvania. A lot of what happens in nature lends itself to a long line; it seems to invite looking at space and time more generously than we might when we’re inside.

In Another Country, you pursue the lost presence of the red wolf in the Cherokee Mountains, though you know the wolves are never going to reveal their mystery fully, and you study the lost Cherokee language and contrast it with our own more limited language. Are these elements together to emphasize a bond between discontinued languages and nature’s continuity? Is this one way that "the complexity of language was born in the complexity of nature"?

Yes, yes! It’s wonderful when you see that enacted. In the new work I’m doing on the coast of Maine, Time and Tide in Arcadia: Seasons on Mount Desert Island, I find the language has the enormous compression you have ecologically at the Coast, and also an exchange of energy, because you have the world of tides. And that’s the underlying fact and the metaphor, that kind of landscape. The compression leads you to try to find the words that are the thing itself. Where are the legitimate figures of speech that are connected to the metamorphosis—to use the literary term—that takes place in tidal pools, and in tidal zones as you watch that change every day? In Another Country the whole pursuit was to try to look at things in space so carefully—geology, wolves, and vestiges of Cherokee culture—so sharply, that time moved, deepened. That’s the work left for nature writers, particularly now, when we’re so disenfranchised politically. The work has to go on. The work now is just to continue to investigate the deepest relations between consciousness and words, and for our species that must be at the level of language. I think it’s close to the primary work for nature writers. It’s not new—it goes back to Heraclitus; it goes back to Thoreau—to be thinking about how words are related to the deep ecologies, and to our sense of place, space and time, but not in a precious way, or in a self-conscious way. Maybe we bleed a little of our own sensibilities into it. But for me, a little of that goes a long way. I don’t do a lot of storytelling of that kind. So I need to find the stories within that connection. The work also lets you indulge two things that a lot of us like to do: spend time outside, and spend time with books, inside. What could be better?

There’s such a lot of contradiction and friction in your work, and in the approach you describe, since you seem to aggressively reject and embrace the metaphors of earth simultaneously—you honor both the rejection and the embrace at once. How do you shape such constant conflict?

You give it buoyancy. This sounds arrogant, but when you spend so much time with your subject, the contradiction gets enlivened. You don’t make it go away. You come at the red wolf from as many angles as you can. You come at it by reading biological history, by interviewing biologists in the field, by spending time in the wolf pens watching wolf personally, camping out in places where wolves might have been, reading mythologies about wolves. You’re doing that not to make the paradox go away but to make it be as interesting as possible, to let it be a paradox in the Emersonian sense, that is, something permanently and instructively contradictory in the relationship between our consciousness and nature—or a koan, in the Zen sense.

I study, teach and write a lot about Native American mythologies, and most Native American mythologies will go back to the paradox they are shedding light on. It’s the reassuring difference between mythologies and theologies. Mythologies let truths glow in the dark, contradict one another. Theologies are hellbent on things being one way or another way. We know the personal unhappiness and political violence that leads to. So nature writers always have the advantage of being wolfish and fox-like, understanding things from as many angles as possible and trying to create a prose line that will present them with all the edges, and leave it there for the reader. It doesn’t go away. If you succeed in a personal, artistic way, you’ve worn away the dualism language tends to give us. If you’re writing well in prose, you can make rock and the word "rock" be the same thing in a sentence. You can make the word "wolf," and wolf be the same thing in a sentence. Thoreau has that wonderful line about wanting to pick up words with dirt still clinging to their roots. We all know it’s a romantic and mistaken idea of language—that language grew out of the earth—but it certainly evolved out of our consciousness, dealing with the opportunities and emergencies of evolution. Our brains are canny because the world is canny. Our brains are complex because the world is complex. Language is the cultural reflection—but because we use language in such a utilitarian way most of the time, you have to write a lot of prose and poetry to get back to verse lines or sentences that fuse them again. I think that’s what the literary arts are about. Our language only survives in literature. It’s not an elitist statement, or the statement of a literary person. The language of politics and business, and in my opinion, religion, is bankrupt because they are used to conceal or to manipulate. English works because artists use it.

We deal with the notion of language extinction with the same sense of emergency we deal with species extinction. There’s something profoundly unsettling in a culture that would allow someone else’s words and grammar to be erased, or to go extinct. So the issue of our own language becoming weak and of other languages being allowed to go extinct—and the stories that they tell becoming invisible again—is an interesting emergency, and it is a healthy emergency for the work of the 21st century. The world thinks it’s busy creating some sort of consumer global economy. This seems to be the big business of the day, but the real task is the task of preservation. How much can be saved? How good can we continue to be, either as writers or as artists, regardless of whether or not we have any power in the world? Poems still live; stories still live; and books still live. It’s kind of exciting to understand that’s where language gets saved or lost—in the writing.

Do you feel a nature writer has a moral obligation because of that?

It’s pompous to claim it, but it would be disingenuous not to claim it. We talked earlier about the wonderful quote of Thoreau’s from Walden about "the discipline of looking always at what is to be seen." Things have the respect of our gaze, if you want to go in a more Buddhist direction about it, though I tend not to go in that direction. To that extent, yes, there is a moral imperative. You teach children to be curious, to be smart, to be funny, to be thoughtful, to not write anyone or anything off. The notion that being interested in nature is an option has always confused me. There’s no box to check "yes" or "no." There is in politics, but politics doesn’t teach us anything of value about these things. The wonderful thing about nature is it gives you an enormous subject without you having done anything; it’s just there for you. If you don’t have a story in mind, which I often don’t have, nature gives you the complete palette. There’s plenty of work. It’s not easy to do it. But it gives you the full play of things right off the bat as opposed to having to create characters and situations.

You mentioned earlier your preference for not including your own sensibilities too much in a piece. That exclusion, which any reader will notice, raises questions of identity. How do you place yourself in an environment you love so much, yet still largely exclude your self? Of course, there is a vast company you travel with—all of the nature writers and poets from the past who are informing your moment to moment experience as you witness and respond—and yet there’s an almost complete absence of other human beings in contact with you. What is your sense of self and community as you travel? Why do the voices of the past compel you in a way that voices from the present don’t?

That’s correct— there aren’t people. I realized that early in Hunting from Home. I don’t think there’s another person in that whole book. I made the decision early on to not be anecdotal. Sometimes I kind of say, "Oh, I walked here with friends," so I don’t seem like some complete troglodyte. In Another Country I’m much more inclined to let people be in the book if they know things my reader needs to know—the wolf biologist in the wolf pen—I loved to see people doing work outside. But the governing consciousness in the book is mine, not as an act of ego so much, but as if to say that’s where I want the camera for the reader. I want the reader right behind me, right over my shoulder, as though we’re one person listening and looking at the world.

I don’t have an appetite for anecdotal story nature writers. That scratches my mind like a scratch on a record—not because it’s not good, but because it’s not what I do. I’m a camera kind of consciousness in my books, which is sometimes a liability, because you’re stripping yourself of the story potential. Nothing gets said; nothings gets done; nothing happens. So it puts enormous pressure on your ability to describe what is there, to animate nature, and to let nature be the presence. So the task is static in the beginning. The identity is, I am what I’m looking at. I think in this way I’m trying to be a lyric poet, which is to say, I am what I see; I am what I think and what I feel. As you rightly point out, I’m much more inclined to bring in the company of other writers. They exist for me as a kind of music, as a tradition of thousands of years, trying to look at the world, the universe, in this intent way.

Again, I think that is sometimes read as a kind of anti-social thing—that’s not what it is. But I’m not using books to tell stories. Publishers love stories. They want the angle: "What happens?" You can’t say in a book proposal, "Well, nothing is going to happen!" The question of the identity of the nature writer—well, I’d like to write an essay about that, answer it in a separate way. It’s always a bit odd. There’s an obsessiveness to it that’s attractive and in some ways probably off-putting to people. But there’s a practicality to it. I couldn’t do the kind of fieldwork that I do in company. I love being out with people, but that’s a different kind of a day. But if you want to go into a forest and understand what a forest is, you go in, and you sit on a stump, and that’s it. Watch for a day. I call it a dark-to-dark. You’ll have an essay at the end of it. You can do the same thing in a tidal pool. In a kayak. In a canoe on a river. I don’t know where that impulse comes from; it’s just what I do. To me, there’s something reassuring about just setting myself up as a tripod and being a person looking at a particular scene, and beginning to assemble it as an emotional place, a psychological place, as a scientific place, as a place where myths were told, or where those instructive Emersonian paradoxes might wait.

And your style in doing that is so apparently you all the same, so steeped in implied, intimate self-revelation, unlike any other nature writer I’ve read. Your personal love for place comes through in a subtle but equally potent, way.

Yeah, that’s who I am. I felt that so strongly in Another Country. I don’t want to imitate that prose style, but I knew when I was writing it. I felt, That’s it! That’s what I want! I’ve heard writers talk about this and I never believed them before, but I’d wake up and there would be whole paragraphs in my head. I could feel I was putting language together in a way I was striving for. In retrospect, the phrase I like is, getting weathered. You want to be weathered to your subject so that you don’t look like a nature writer. Everyone complains about the niche they get put in. You don’t want there to be a whiff of a notebook or pen. You just want to see someone weathered to the landscape. I do give myself credit for this, but I spend a tremendous amount of time in a place when I’m writing about it. There are a lot of hours behind those sentences. I don’t think you can shortchange that process. The letters I most like getting from people are the ones that read, "Boy you spent a lot of time in that place! You were not doing a hit-and-run job like a tourist. I’ve smelled wood smoke like that!" Or "I’ve seen campfires like that!" Or "I’ve listened to a river like that!" That’s what writers and readers get to share, those hours, in the real sense and in the devotional sense of the Book of Hours. Poets do it all the time. A lyric poem can expose a decade of the poet’s life. I’ve been drawn to that, to not shy away from the seriousness of that. It’s socially acceptable or literarily acceptable because it’s about an objective world, but it’s an intense, personal seriousness.

In everything you write—and in so much that you say—there is always this ecstatic experience, your search for that. You use the words "holy" and "sacred" and remind us of Thoreau’s observation that "Heaven is underfoot." Is this a need or hope for unearthing the sacred?

Well, I always misquote Thoreau, which is interesting. He actually said, "Heaven is also underfoot." I’m not inclined to cede anything to heaven these days, I guess. I’m quite amused to see how my mind changes things. I tell my students I’m a card-carrying secular humanist. There’s a rich tradition, and there should be a good anthology, too, of secular exploration of the sacred—detach spirituality and ecstatic sense of wholeness from theology, and just accept that even those of us who love the earth in all of its tangible details are not necessarily saying, This is all that there is. We’re just saying, It could be enough, and I will not get to the bottom of this.

I enjoy teaching Native American Literature, because there are so many positive values coming up out of the ground rather than down from the sky. I am suspicious of a hierarchical, metaphysical Western view of the sacred: it becomes the property of a smaller group of people, and it becomes a political and economic tool. If the sacred lies outside of anyone’s door, it just becomes democratized, as Dickinson and Thoreau and Whitman knew. Some people find that a heartening idea. Others are threatened. I mistrust metaphors that try to get above the earth. I’m interested in the universe as a physical place—the things physicists find out are good, but as soon as a sentence or a verse line asks me to give up my sense that the earth is home, I’m as suspicious as a child as to why that is. The idea that the sky is enough for you seems like a good, spiritual idea, but it really threatens and scandalizes a lot of people. You don’t need heaven? That’s a very dangerous idea! I don’t understand that. The literature of religions interests me for its own aspirations, but why what we can access with our senses is not enough to mull over for a lifetime, until we get to see what else there is or isn’t, that confuses me—the current political climate in which "secularists" are being accused constantly on right-wing radio of being culturally treasonous. Well, this country was founded by secular humanists, but you can’t say that anymore. I don’t want to psychoanalyze myself, but I was raised Catholic and with the expectation that there is an overarching structure to things. Maybe it’s fair to say you don’t give that up—you just look for some other kind of structure. I was exposed to the significance of the sacred as a theological thing, and I rejected that. Why would you see a bird and not assume that that was sacred—not assume its being was as important as your own? Why would you see a tree and not assume that it was sacred? Who needs theology for that? I would fully admit to looking for the sacred, but I look for it in the local. I keep my gods close at hand. I know theology pretty well. I watch it like a hawk. I don’t get it. I do get the earth. So, nature writing is a place where secular humanists get to practice a craft.

What’s happening with your next work?

I would like to go to Italy and base two books there, one on the small town that my father’s mother was from in Southern Italy, Constantine d’Albanese, and another about going back to the town where my father’s father was from in Sicily, Bronte, in the ring of towns around Mt. Etna. I’ve thought of living with Etna. I’m partly just doing the pin-in-the-map thing, but I’m interested in my Mediterranean background and have been reading a lot of literature from those regions. I’m interested in where my nitty-gritty consciousness comes from, in the landscapes of my ancestry—for bright and dark reasons. But also I want to force myself into culture and music and to learn about the language—which reflects back on your earlier questions—to do what I do there, and be forced into another self. Slowly, I’m working on a volume of poems, Learning to Travel. That title gets the idea, to think about my own background, going back a bit in cultural time. When my father’s mother died a few years ago in Brooklyn, I realized that the last European in the family had died. Now I want to see what’s left of a European, in me. For example, there are wolves in Italy. I’m interested to see what would happen to my prose, looking for wolves there. There’s a chestnut tree that my late grandmother remembered. And there’s enough nature there, enough history, enough local gods to keep me busy.

Is that about always looking for home?

Oh, yes—I’m teaching a contemporary American Lit course, and look at the books I’ve chosen! Kerouac’s On the Road, N. Scott Momaday’s House Made of Dawn, Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony, Edward Abbey’s Desert Solitaire, Barry Lopez’s Crossing Open Ground, and the poetry of Gary Snyder, James Dickey, and A.R. Ammons. They’re all writing about people looking for where their homes are!

That reminds me of your one description in Hunting from Home of time spent away with other human beings—a wild, joyful experience you shared with friends in Russia, and your sense of being steeped in joy, of belonging with them—and you ask what was wild about that moment with human beings?

I want to see that in the Italy book, too. I’d even use that exact scene in the proposal. That experience happens with people more when I’m away. You go someplace, and things click and you feel at home, even though it’s supposed to be foreign and new. I’m interested that you mention that scene, and in that scene itself. I’m not sure what’s going on in there. That is a window into the book I foresee about Sicily and Calabria. Those are the landscapes and people I’m related to. I read a lot of short fiction from the 19th century, before my Italian ancestors migrated. I read a lot of Italian short fiction. It’s somewhat depressing. It’s a tough, hard, very flinty culture. There’s a kind of psychological wildness that says we lean on our sense of culture enough in a foreign culture so we see things more vividly. The relationship between what we call "wildness" in nature and "wildness" in culture would be evident to us, as I felt it was in that apartment in Russia, which I also relate, ironically, to the apartments I knew in Brooklyn as a child—those apartments and towns I now want to go back to. You put your finger on a thread. It does connect, all of it, to home.

And what about your next book, about Maine? How will you begin that work?

The limits of the book are purely practical. It made most sense to start with a distinctive part of the coast of Maine. So, Mt. Desert Island, which is well known, was, of course, an obvious choice. Acadia National Park preserves enough of the island so that you have a piece of what they call the climax of the coast of Maine; it’s still there. You start with the obvious—enjoying a place the way that people do. You have granite mountains coming down to the ocean; you have some of the most beautiful headlands on the coast; you have glacier carved lakes; you have the ecological compression of the coast so you get a fine maritime forest; you get tremendous variety of bird life, marine life. The first thing to do is to go out and learn it. One of the things I like about this kind of writing is just the practice. You have to go to a place for whatever reasons and learn everything about it that you can, partly with your own five senses, just doing fieldwork with binoculars, a pad and a pen—the best kind of days. You get out in a kayak, do a dark-to-dark, just make sure that you’re out on the beach or in the woods before the sun comes up, and make sure you’re pretty much in the same place when the sun goes down, and you’ll get a feel for the place.

When I’m not there, I do a lot of research and reading. You have to read through a lot of marine biology and geology just to get a few earned adjectives into your own prose. So you need to learn the science of a place. As with Another Country, I always want to learn the mythology of a place. There isn’t a lot of mythology saved from the Native Americans of that coast. A little bit, from the Passamaquoddy and the Penobscot and others up into eastern Canada, but you can still read a lot of archeology and still get a sense of how they hunted, how they made kayaks, how they ate, how they migrated over the seasons. You’re just forced to do a classic liberal arts curriculum. You, in a sense, just go to college again—I’m a great fan of the liberal arts, I worry a little bit about the future of them, of that secular humanism I feel so defensive about—but you just do that. Everything in language, everything in art. I go to museums anytime I’m near one that has some of the 19th century landscape painting that was done on the island—Thomas Cole and some of the others. You go see them. You go to Hartford, see paintings of the coast of Maine there. You just pick up every thread. Down here in Pennsylvania, I see some of the birds here in winter that are going to be nesting up there in the summer. You get the connection of the migration of birds. There’s a little bit of history in the book, but there’s been so much already written on the history of the coast of Maine. Again, this may seem like an anti-social book. There are not going to be stories about people, or folksy things. I don’t do folksy. I don’t like folksy. It would be nice to spend a year lobstering in Maine, but you can’t do that with the kind of incidental contact I will have.

Will you prefer to be on the coast as you’re writing about it, or to collect information and write elsewhere?

My preference would be to live on the Island for a year, to use a conventional framework of living for a year in a place. It’s been done before—goes back to Hesiod and before. It has the virtue of being a huge part of the way things are. A good writer ought to be able to do a lot just with the four seasons. I’ll have to fashion essays out of very intense relationships to other spots, which I actually mapped out last summer. I know what tidal pools I’ll visit; I know which mountain summits I’ll climb, which coves I’ll kayak, which lakes I’ll canoe on. I need to invent a different kind of essay for this book, where I can earn my right to be there. I feel an obligation to earn the right to be in these places. The only way a writer can earn that is by creating good sentences about it. I think I’ll have to be narrowly focused and quickly get to a worthwhile depth. The hours will be more literary, highly composed. I don’t have the "waste" of time I prefer to have, now that I’m teaching full-time every year. I want to see something a hundred times and describe it once. But I’ll have to see it once and describe it once. That’s good discipline. You should be able to take your skills anywhere and do it. The values of the place, bird life, whales, pelagic birds offshore, maritime forests, bedrock, tide—in and out, in and out all the time, a tremendous transfer of energy, very fundamental—and all happening with a lot of tourist distraction. But distractions can be edited out. You only have to walk to a quiet place, just get a sense of what nature makes of this place? Hopefully, it’s a short book. It’s hard to write short books! But it ought to get the reader to the center of every one of those kinds of experiences that they can have in well-written prose, without any explanation of what I’m doing there. In some ways it’s austere, no pretext, just words.

In Another Country I had wolves to follow; I had an excuse. There’s no excuse here except the place. But the preoccupations are like in Another Country—a lot of mythology, a lot of science, a lot of field experience, a lot of what can be made of the place. I get more help in the beginning from science and the arts. Just start reading marine biology and a narrative emerges. Nature writers are notorious for stealing from science, pretending we know more than we know, learning very quickly what we need to know to create the next sentence. It makes us seem smarter than we are. Explaining things from our own point of view is part of it. That connects back to the theme of regard, and of sacredness.

Where are you headed after your current projects?

I want to write a volume of good short stories. Put those on the shelf. I have some in progress, and I like what they could be. I’m thinking of just getting better at what I do, at writing well, in the ways that I conceive of that task. I want to leave the traces of what my intentions were on the page—if anyone cares to look at them. I know I’m spending my time well. That’s really all that matters.