Spring/Summer 2006, Volume 22.3

Art

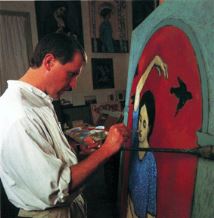

Brian T. Kershisnik

Art as Alchemy: Capturing the Sacred State of Discovery

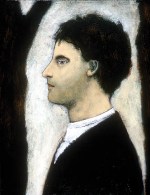

Brian T. Kershisnik (MFA, The University of Texas at Austin; BFA, Brigham Young University) has exhibited his work widely: Salt Lake City, Sante Fe, Seattle, Portland, Austin, Chapel Hill, and New York City.

Because Kershisnik's father was employed as a petroleum geologist, he grew up in Luanda, Angola; Bangkok, Thailand; Conroe, Texas; and Islamabad, Pakistan. He graduated from high school early, not because of sterling merit, but because the American Embassy in Islamabad was burned and he was evacuated early. After a year at the University of Utah searching in vain for vocation, he served a mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Denmark. He returned to the USA to study art at Brigham Young University, where he received a grant to study in London for six months. After graduate studies in Austin, Texas, he and his family moved to Kanosh, a small town in central Utah where he paints and works on his house. He and his wife Suzanne are raising three children and a black dog.

In a sense, more profound than I can say, I don't know what I am doing. When people learn that I am a painter and ask me what I paint, I have difficulty answering. Usually those asking are seeking only the short answer and must be embarrassed or annoyed at my stumbles and what must look like attempts to conceal something. I hope that my responses have become less ridiculous and not less illuminating.

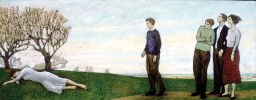

My current conclusion as to what I paint is that I don't know, and I'm trying to be more at peace with that awkward reality. I am not painting about something I have learned and wish to explain, but rather something I am trying to understand myself—the problem of being this particular human being in progress. I don't paint people to show you who they are, but as part of trying to discover who they are, and I fall in love with every one of them. The questions involved in a painting, if I know them at all, are very difficult to articulate. I follow a hunch in search of a question, and in this process, quite unexpectedly and even unintentionally, something of another world, of the other world, something of God leaks out. Then, whether my abilities are frail or splendid, they will be woefully inadequate, and that is exactly where I want to be—anxiously engaged. Painting, for me, is anxious disciplined pursuit, trying to sense when and how to get out of the way so what is coming can come. The benevolence, indifference, or even malevolence of each idea must be discerned in the process which can take days, weeks, or years. Each experience has unique qualities, and so one never does, must never, get it down or reduce it to an easily regurgitatable process. As I get older, and more experienced, my sense of what to pursue or discard gets better, as does my appreciation for the sacred state of not knowing exactly what you're doing, just knowing you should be doing it. What is truly surprising is the sensation that comes to me that I should be doing what I am doing. Yet, like an act of grace, it persists unbelievably.

[Click on images to see larger.]

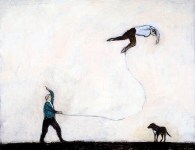

While driving through a suburban neighborhood on the way to visit my parents, I saw a man in his front yard practicing his cast with a new fly rod. My comment to my wife was quite accidental. "Look, that man is practicing flying." She is used to my making such mistakes and, rather than correcting me, suggested it was a good idea for a painting.

The initial paintings exploring this idea were, not surprisingly, of people practicing flight. Usually the people were landing on their heads, but the tragic (or at least painful) consequences of their failed attempts can be seen in a different light when it is understood that they are practicing: they will not always land on their heads. As I considered this and continued thinking and sketching, I realized, little by little, that the issue of practice had been vital to my work for many years, though I had never named it.

How splendidly human it is to practice. Everything we do is practice, if you will see it that way. This is an optimistic perspective; it suggests that the awkwardness, failure, or drudgery of our current task will, sooner or later (and probably gradually), give way to something lovely, even beautiful.

For reasons that are difficult to articulate, art is vital. As we experience it, we increase. This is not necessarily to say that we gain information, but rather that we become part of a larger thing, and in some way we know or are known more completely. I believe it is this illusive quality that unites art as diverse as that of Rembrandt and Paul Klee. In this sense it is not a new thing that must continually be done in art, but rather the old thing, continually explored by new individuals.

Perhaps art is a rend—a hole, a place where a seam in the body or spirit did not quite come together, and as a result another pure authentic reality leaks out, not necessarily in intentional ways. Perhaps artists are the ones who through poetry, dance, story, music or what have you give shape to the issue and substance of that reality, such that it can be perceived as something more than just a mess that needs mopping or therapy.

I believe that the power of art is derived from this pure authentic reality, a reality which is concealed for what I trust are good reasons. Not all leaks from that world are to be broadcast or celebrated. Benefit can certainly be derived from these intentioned or unintentioned leaks. But only if treated with care. I believe that as an artist I should exercise such stewardship. The invasion to ourselves in creating art as well as the invasions to those who receive the art make it clear to me that the process should be handled with appropriate care, affection, concern and not least, virtue. Even in my pictures which are humorous and whimsical there is an element of danger because they must in some way acknowledge or address the existence of the very center of truth. In that truth, I have found that there is plenty to laugh about, but not at. There is plenty of comfort if I can learn how to receive it. There is plenty of joy, but it must have a foundation. And there is plenty of sorrow, but not despair.

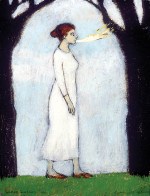

I am a painter of the idea of a thing rather than its physical reality, though obviously I am influenced by that as well. In exploring the idea of a thing, I seek the boundaries of what I don't know or haven't experienced. As I paint, I am myself interested to watch and see who these people are and to consider what they are doing and why. I seek to be more of a participant in the process rather than the creator of it. The purpose of a painting—if I ever discern it—often takes me long after its completion to get a handle on, and it is very seldom distillable into a single paragraph, if it can be articulated in words at all—at least words that I have access to. I rather think that these are paintings of the memory or anticipation of feelings. I suppose that people who respond to them must recognize the resonance of similar anticipations or memories. Art is not just the transmission of an image from the eye to the finger without picking up something along the way. There is no poetry where there is only facility. The knowable, optical world is not art when it is the culled, unmediated transfer of visual reality. Art is not biopsy; it is alchemy. An artist is someone who can give us a mechanism that allows us to feel what we have been wanting to feel anyway. My most powerful work is almost always surprising to me.