Winter 2005, Volume 22.2

Essay

Ron Fischer

The Language of Stone: Stories from Pictograph Caves

Ron Fischer received an MFA from the University of Montana and a DA from Idaho State University. His play A Dance on Crumbling Earth won the Montana Centennial Production Award, and his collection of stories Journeys into Open Country won a Montana Arts Council's First Book Award. He teaches at Minot State University. "`The Language of Stone,'" he says, "sent me on a quest to find the stories inside those images. I learned much about the Native way of thinking and of doing things, especially from Joseph Eppes Brown, as well as Linda Olson and Calvin Grinnell."

Seven miles southeast of Billings, Montana, within a jutting outcrop of rock, stand three extraordinary caverns called Pictograph Caves. What makes them extraordinary involves the rituals once enacted there by the Absaroke, that is, the Crow people of Montana and Wyoming, and the images they left inside them. William Mulloy, the archaeologist who excavated the caves in the 1940s, cataloged those images by having drawings made. At that time, Mulloy, thinking in terms of the individual and that artist's vision, believed that the meaning of these images "must remain obscure […], for such symbolism is a highly individualized thing, capable of decipherment only by the original artist and his community" (119). Mulloy does suggest the importance of community in helping us understand these images. Indeed, we can explore the cultural connections embedded in the images found in Pictograph Caves by learning about the Absaroke people through the teachings of their religious leaders, their cultural practices, and their myths and legends. By discovering the rich Absaroke heritage, we can begin to explore the connection these images have to Absaroke culture.

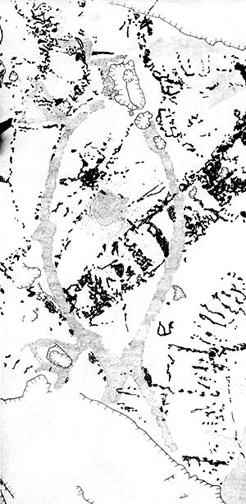

Unfortunately, just when we have reached a better position to explore the connections these image have, the pictographs themselves are fading away. In the 1990s, water from a stock pond seeped through the cave walls and began washing the colors away. To preserve an accurate record of these images, Linda Olson, an art professor from Minot State University, North Dakota, made tracings for the Bureau of Land Management. The images reproduced here are Olson's tracings. In their detail and preciseness, they give us far more than Mulloy's individual drawings. We can see the way the images relate to each other. Those relationships help guide the way in our quest for connections.

Just as an artist shapes the images, culture shapes the artist. The artist may choose to draw a figure on a cave wall because of the cultural importance it carries. An Absaroke artist may have painted the figure of an elk for the sheer joy of drawing an elk, yet even as the artist composed it, he knew his culture, knew that the Absaroke view the elk as a spiritual force, as love medicine, for the Absaroke link the elk to the power of attraction. What figures do we see in this stream of images, and what links do those figures have for the Absaroke? To explore cultural connections, we first need to identify Absaroke practices depicted by the image, and then open the collection of Absaroke legends and stories to explore how those practices are viewed.

Fasting for a Vision

|

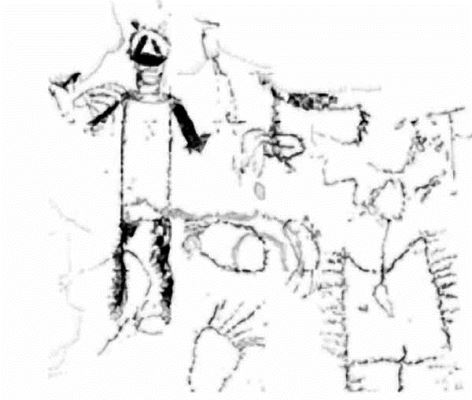

The central and largest figure emerging from the cave wall is a shield-bearer with weeping eyes. The enthnographer Rodney Frey, author of The World of the Crow Indians As Driftwood Lodges, describes an Absaroke practice called a bilisshiissanne, a vision quest, a term representing a ritual fast from water and food (77). Crying is a crucial part of this practice. As an Absaroke medicine man explained, "When a man fasts, he wails, `He That Hears Always, hear my cries. As my tears drop to the ground, look upon me.' While he moans thus in his despair, he grovels on the earth and tears up grass and weeds in anguish of spirit" (qtd. in Curtis, The North American Indian, vol. 4, 53). Through the bilisshiissanne, the faster seeks to become the son or daughter of a spirit, an Iilapxe, or "Medicine Father." Frey explains that the faster must show that he or she "is destitute, alone, in need of help, like an `orphan,' aleeleete, meaning `one with no possessions, one who has nothing'" ( 80).

Perhaps the tears we see on this figure are the tears of a faster. From Absaroke literature, we learn that this practice often begins with a very personal and deep need. In her life story, Pretty Shield, a Crow medicine woman, said her fast for a vision came from a terrible wound in her life: "I had lost a little girl, a beautiful baby girl. I had been mourning for more than two moons. I had slept little, sometimes lying down alone in the hills at night, and always on hard places. I ate only enough to keep me alive, hoping for a medicine-dream, a vision, that would help me to live and to help others" (qtd. in Linderman, Pretty Shield 165). She seeks a vision, not only to recover from her personal grief, but to become someone who can help others. When Pretty Shield received a vision of a lodge that contained in abundance all the necessities of life, she recovered her will to live and an Iilapxe: the ant.

A Crow medicine-man told the ethnographer Edward Curtis about undertaking "eleven long fasts" but receiving only "two visions" (qtd. in Curtis, North, vol. 4, 59). Performing a fast does not guarantee a vision. Much depends upon "doing it with sincerity," diakaashe, that is (Frey 142). The vision quest was commonly practiced by plains Indians, and the need to perform the ritual in a sincere and pure manner surfaces time and again in the stories. Lame Deer, a Lakota medicine man, tells the story of a young man who wailed bitterly but who never received a vision. Finally, he had to be scolded: "You went after your vision like a hunter after buffalo […] You thought they owed you a vision. Suffering alone brings no vision […] A vision comes as a gift born of humility, of wisdom, and of patience" (72). The lesson of this story? The seeker cannot find the divine, not even in Pictograph Cave, or anywhere else in the world. Such a spiritual force must find the seeker. If this figure of the weeping shield-bearer is a faster, it is a large reminder about the proper manner for seeking a

vision.

Shield-bearers who take up the Quest

|

The panel to the left of the central figure begins with a line of four shield-bearers [below] who seem to be undertaking some kind of journey or quest. The first wields a club; the second, a coup stick; the third, a spear; the fourth, a pelt. Little people emerge on the path they walk. Such a quest may sometimes involve encounters with the wondrous. A scout or wolf, his shield on his back, seems to be standing just a little ahead of them.

The purpose of a quest varied. Some quests involved hunting, or war, or horse-stealing or wife-getting. The vision a seeker received before undertaking a venture indicated the success or worthiness of the quest. Because the vision was so crucial, the medicine linking the one who received the vision was brought on the journey. This line of figures matches the description ethnographer Robert Lowie gives: The person who carried the medicine "walked in front of the rest, and usually no one was permitted to go on the right of this leader" (Social Life of the Crow Indians 233). Were any of these regulations broken, it was believed some mishap would befall the quest.

The quest story is at the very core of Absaroke tribal identity, which makes the appearance of a quest in Pictograph Caves seem quite natural, essential even. The Absaroke belong to the Siouan language family and originated as eastern woodland Indians, their ancestors living near the Great Lakes. When the buffalo disappeared there, the tribe moved to the area of St. Paul, Minnesota, which turned into a place of affliction, people dying of hunger and cold, and from hostile Lakota attacks. They journeyed westward to the "Sacred Waters," or Devil's Lake, North Dakota. There a visionary experience turned this history of nomadic wandering into a quest.

In his book From the Heart of the Crow Country: The Crow Indians' Own Stories, tribal historian Joseph Medicine Crow tells the history of the Absaroke people as a quest story, the primal quest that gave the Crow their sense of identity and their sense of character:

[T]wo chiefs—No Vitals and Red Scout—fasted and sought the Great Spirit's guidance on their perilous journey. Red Scout received an ear of corn and was told to settle down and plant the seeds for his sustenance. No Vitals received a pod of seeds and was told to go west to the high mountains and plant the seeds there […] The Great Spirit promised No Vitals that his people would someday increase in numbers, become powerful and rich, and own a large, good, and beautiful land! (19)

Red Scout's band settled along the Missouri and became the Hidatsa nation of North Dakota. No Vitals, "motivated with the desire and dream of someday receiving the blessings of the Great Spirit," continued the quest and led the tribe onward. They went to the Cardston, Alberta, area, then journeyed south, going as far as a lake "so salty that they could not drink it," most likely the Great Salt Lake of Utah (Medicine Crow 21). They circled southeast to the Arrowhead River, now the Canadian River of north Texas and Oklahoma, then followed the Missouri River upstream. The original band died, but the quest continued until the tribe arrived in southern Montana and northern Wyoming. Fulfillment and blessing of that vision came to the second generation. From generation to generation, the Crow carry the quest undertaken by their tireless ancestors. While we may not know whether the quest represented here is that primal quest, these figures set before the seeker the timeless and tireless determination required in all quests.

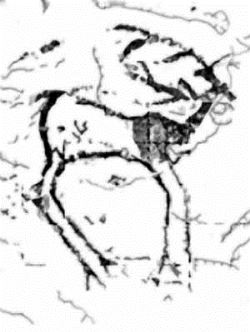

Love Medicine: Elk

|

The small weeping figure just to the left and slightly below the fasting shield bearer also appears to be fasting. Lines connect that figure to the elk figure above it. Ethnographer H. H. Blish writes:

The Elk was closely associated with the Indian idea of love and sensual passion. Supernatural power lay behind manifestations of sex desire: Consequently, numerous mythical creatures were thought to control such power, and of these, the bull elk was the most important. (qtd. in Brown, Animals 18)

Elk's power of attraction lies in its bugle. Robert Lowie in Social Life of the Crow Indians reports that to obtain that same power young men courted their lovers by playing flutes made of elk bone and went "round the camp after night fall, blowing flutes for their mistresses' amusement. An especially long flute that was said to produce the sound of an elk call was used for charming women" (221). The lines in the cave image that point toward Elk may be the "medicine" of Elk's charisma, the force that pulls things to itself, and the tears of the figure below it may suggest a figure fasting for Love Medicine.

The Crow story collected by Lowie called "Huàraáwic" puts before us the power and danger of love medicine (Myths and Traditions 196-199). Huàraáwic, rejected by the woman he loves, fasts to obtain a love medicine. His fast works. Elk comes to him:

"Child, there is nothing hard for me as regards all female animals." This elk then turned into a young man […] The elk-man had a flute. He blew it upstream and the deer came running. He blew it across the Missouri and

female elk came swimming. He blew towards the other side and mountain-sheep came running. When they had come, one white one stayed by itself. "Now that young girl you want to marry is that white sheep." (197)

Helped by Elk, Huàraáwic gets his girl, but the story does not end with marital bliss. Huàraáwic has more to learn about love. An ugly woman with one eye comes to camp and announces she would marry Huàraáwic. Under the spell of the woman's love medicine, Huàraáwic abandons wife and friends to live with the one-eyed woman. Years pass before his friends find him: "He was seated as his friends came in. He did not talk to them. They sat down uninvited" (Lowie, Myths and Traditions 198). They undo the love medicine and Huàraáwic admits, "I forgot myself for a long time."

Love medicine has the power to attract but not to bind. The power of pull doesn't necessarily pull things together. It can pull things apart, out of their rightful places, as happened to Huàraáwic. Elk can bestow upon humans the power to attract, the story tells us, but only humans can put love, the power to bind, in love medicine. Whether the image in Pictograph Cave carries this counsel or not, the Absaroke stories certainly do.

Warrior: Bowman, Lancer, and Shield-Bearer

|

Just above Elk, a sunburst surrounds two warriors, a bowman and a lance-carrier. Opposite them is another shield-bearer. Once a faster received a vision, objects like a lance, bow, or shield were marked with images and symbols from that vision. These instruments then received "medicine," becoming wondrous themselves. Two Leggings, in his biography, describes this process. He sought an akbaalia or "medicine man" to help him fuse the baaxpee (medicine) granted him to a shield: "Much singing and smudging and other ceremonies were necessary to make it powerful" (Two Leggings qtd. in Nabokov 119).

Yet, the shield, even imbued with medicine, may not protect. The Absaroke stories suggest that the medicine linked to an armament possesses something more than protective powers. The Crow chief Plenty Coup tells this experience about the visionary medicine within a shield:

Suddenly I saw [Mountain-Wind] drop his shield! It fell to the ground face downward, and when he lifted it he did not turn it, but raised it to the level of his breast […] I did not breathe while he looked at the face of the blue man painted on it. "I see many Sioux scalps," he said, his voice sounding like one who has just awakened from sleep. "And many horses […] but one great warrior is not going back with us. […] Have no fears for yourselves. It is I who will not return home with you today. Feel no sadness. Remember that nothing is everlasting except the Above and the Below" (Linderman, Plenty Coups 280-282).

We encounter the bow, a weapon of attack, and the shield, a weapon of defense, in Pictograph Caves. War hasn't gone away. These images may remind us of the extraordinary power of life and death that such weapons bestow. Absaroke storytelling, however, reveals that such powers require us to use them properly.

Wholeness: The Beautiful-One and the Hole in the Sky

|

|

Directly to the right of the central weeping figure looms a cellular ellipse. In its center rests a dark spot. Lightning zig-zags from its top while fin-like shapes appear on its side. It combines sky and earth images. To the right of this shape, we see a smiling woman who is encircled by a sunburst. Could she be the Beautiful-One we read about in the Crow story "Morning Star—Son of the Sun" (in Linderman, Old Man Coyote, 207-254)? She clutches a digging-stick, used for unearthing turnips. The Crow link the digging-stick to birth, for "Women in labor hold on to a digging-stick" (Lowie, The Crow Indians, 233). Of course, the ellipse may have many possible connections. In linking it to the "Morning Star" story, the ellipse begins to emerge as womb-like, perhaps as the hole the Beautiful-One in that story made between heaven and earth with her digging stick, a passageway between heaven and earth that brought wholeness.

According to Linderman, in the "Morning Star—Son of the Sun" story, the bravest warriors, the best hunters, the handsomest men wanted the Beautiful-One as wife, but she scornfully dismissed all: "No, I shall never marry!" (209).

One day, Coyote lured her into climbing an ash tree. She climbed so high that when "She looked down. […] The World was gone!" (211). Coyote took her to a lodge where she found a sleeping man who radiates light from his face. "Ah! Now she knew that the sleeper was the Sun!" (216).

She happily lived with the Sun and bore his child, Son of the Sun. The Sun asked only one thing of her: "When you dig Turnips, do not dig the Big-one that has many stems" (216-217). One day, her son begged her to do just that. She finally gave in to his pleas with the hope that "This may not be the Biggest-one—the one with most stems" (217). The unearthed Turnip tore a hole in the sky. Below, she saw her people, the Crow, and a restless yearning to return to her people overcame her. The Sun, discovering this, decrees that she and her son must return to earth. In making the climb from heaven to earth, the Beautiful-One plunged to her death, but her body cushioned the fall of her son. He lived and became a monster-slayer, a great hero who removed chaos and harm from the world, and who returned to the sky to become the morning star.

The Beautiful-One experiences both the heights of joy and the despair of loss. Ecstasy and despair—these are the extremes experienced by those who fast for a vision. The Beautiful-One digs a forbidden turnip and opens a hole in heaven that allows wondrous things to happen on earth. Perhaps through the visions sought by those who came to Pictograph Cave, that medicine or baaxpee of order was once again brought to earth.

Power of Transformation: Coyote, Buffalo and Shield-Bearer

|

Further to the right of "The Beautiful-One," we next see Coyote and Buffalo. Overlapping the buffalo is a shield-Bearer whose head merges into the thigh of the buffalo. Buffalo represents a special kind of spiritual experience to the Absaroke. Being "knocked down" by Buffalo in contemporary Sun Dance ceremonies among the Absaroke represents a visionary experience. Frey reports that "A person who is dancing `hard' may see the object on which he is focusing `finally move and show itself to the person.' […] Buffalo may `chase' a dancer, knocking him down. When this happens, the dancer is said to have taken a `hard fall.' […] As the fallen dancer lies on the ground, he receives a vision" (Frey 118).

While the Sun Dance experience is visionary, Absaroke medicine men describe another kind of experience, a transformative experience that imbues an individual with the special powers that make him or her a medicine person. For the Absaroke, Buffalo sometimes bestows those powers, as in the case of Hunts to Die, a Crow medicine man who described this transformative experience:

I had been shot […] In a vision I saw a Buffalo bull, which came and began to fall and roll from side to side. He transformed himself into a man. […] The buffalo sang his songs, and took a live coal and made incense. […] Then he took water in his mouth and spurted it over my body. […] When I awoke I found myself dressed and painted ready to be buried; but I was well, and the arrow-point had come out. The Buffalo gave me three kinds of herbs. After that any person shot in the body sent for me, and my treatment never failed. (Hunts to Die qtd. in Curtis, vol. 4, 56-57)

Among plains tribes, the story of Coyote becoming Buffalo has a wide circulation [Douglas Parks, Myths and Traditions of the Arikara (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996) page 363, lists the tribes who have recorded printed versions of this story (collector in parentheses): Arikara (Dorsey); Cheyenee (Kroebar), Mandan (Beckwith), Omaha (Dorsey), Osage (Dorsey), Pawnee (Dorsey), Sioux (Beckwith), Wichita (Dorsey). I can add Arikara (Parks, Jones and Hollow), Shoshone (Marriott and Rachlin), Caddo (Dorsey)], and carries an important message about the transformative experience. The Crow version of it may come to us in the images found in Pictograph Caves. For the discussion here, I have chosen the Caddo version of this story as told by White-Bread (qtd. in Dorsey, Traditions of the Caddo, 101). Coyote, starving and pitiful, begs Buffalo to transform him into a buffalo so that he can eat his fill of grass. Buffalo agrees to do so, but he must knock Coyote down first. Six times Buffalo charges Coyote, but Coyote dodges each blow. On the seventh, "Buffalo struck him and rolled him under his stomach with his horns and threw him up into the air. When he came down on his feet he was turned into a very young Buffalo" (101). Buffalo tells him not to use his power too often and especially not on "any of his own race" (101).

However, during that same day he tried his power three or four times, and before he had met any one he had tried it six times, and had turned himself into a Buffalo for the seventh time. While a Buffalo, he met one of his own people, a famous Coyote, and so he went up to him and said:

"Do not you want me to give you some of my power, so that you can eat grass as I do? You look as though you were very hungry."

"Yes," said Coyote.

"Well, all right," said Coyote-Buffalo. "Go off a short distance from me and stand there and face the other way. Do not run, but be brave as I am. Close your eyes. Now, I am ready," and so he started at him, but the other Coyote jumped out of the way every time until the last time came. Then Coyote stood his ground, and Coyote-Buffalo rolled him under his stomach, and they both went up in the air and came down on their feet. They were both Coyotes, and they stood looking at each other for a time; then they separated and went off. (101)

In Pictograph Caves, the overlapping image of the shield-bearer and the buffalo may suggests some kind of transformative experience. The presence of misshapen coyote, either mutating or off-balance as if being knocked down by the buffalo, may evoke a cautionary tale similar to the Caddo Coyote Becomes Buffalo story. The transformative experience brings transcending power, but such powers, the stories tell us, require great prudence in their use.

Hosting the Spirit Helper: Bear-Man and Woman

|

Still further to the right, we see Bear-Man and the fringed Woman near him. The bear is a creature that walks on all fours as well as on two legs, that is omnivorous, eating meat and plants, and that possesses long claws for digging roots and herbs. What we see could be a practice associated with the the Absaroke ceremony called the Bear Song Dance. In that dance, individuals whose physical bodies have become hosts to medicine helpers reveal their spirit lodgers. Curtis gives this description of the Bear Song Dance:

It was an occasion for all whose hupadhiu, medicine, had entered their bodies and become batsidhupe, to exhibit their supernatural power. Each of these, as he felt his medicine-spirit moving within him, came forth into the open space, threw his arms around a pole from which hung a bear-skin, and leaned his face against the skin […] and then his medicine itself, whether snake, bear-claws, horse-tail, or what not, came out of his mouth, withdrew and disappeared down his throat, all without aid of his hands. (vol. 4, 178-179)

Like the Bear Song Dance, Absaroke stories about "Lost-Boy" involve bears and combine the transformative experience with a revelation experience. Pretty Shield's version of "Lost-Boy" highlights the transformation of a wounded person into an akbaalia, or medicine man (Linderman, Pretty Shield 183-195). The story begins when a boy stumbles and falls face forward into a lodge-fire. His face is badly burned. Unable to face anyone, "he stole away and did not return" (183). He is lost to the tribe, and in this story becomes the concealed helper who must be revealed and returned to the tribe.

Years pass. One day, two Crow women, a mother and daughter, are captured by Lakota warriors, who enslave them until the two attempt an escape. They flee the Lakota camp and hide for days. Finally, a white bear appears to them. The mother tells her frightened daughter that "animals often help people who are in trouble. Perhaps this bear-person will help us" (185). The bear provides food for them, protects them, and reveals that a flood prevents their return to the Crow people. Four years must pass before they can safely journey home. The white bear leads them to a place where they can find a helper.

At that place, a horribly disfigured man appears to them. Is he the white bear, transformed into a human? A friend of the bear? Lost-Boy identifies himself: "I am Lost-Boy, the one who fell into the lodge-fire," he said, turning away his face that was terrible to see. "Come down into The-Black-Canyon and live as my neighbors. I will kill your meat for you, will help you. I am a Crow. Come down," he finished, stepping off The-Black-Canyon's rim into the thin air, as before (Linderman, Pretty Shield 192).

He returns the women to the Crow village. They beg him to stay. He does and marries the young woman he has protected. He is revealed as Lost-Boy, who "had lived in the rock with The-Little-People ever since the day after he had burned his face. The-Little-People gave Lost-Boy a big medicine. He became a great healer of wounds" (195).

Lost-Boy cannot undo his physical disfigurement, but he possesses a gift for healing. Lost-Boy as protector and healer is far more important than his disfigured appearance. Crow legends carry the same revelation as the Bear Song Dance: What we are on the inside is what counts. The person who develops a cancer, loses a leg, goes blind or suffers a stroke and becomes paralyzed painfully knows the changes illness brings, both physically and to the deepest levels of being. Yet the Bear-Man stories suggest that character counts more than appearance, more than physical condition. Tied to Bear-Man is the theme of healing and a reminder that our lives go beyond the physicality of our bodies.

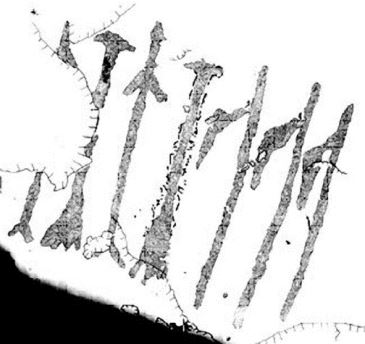

Circle of Life and Death: Coup Sticks and Flintlocks

|

|

On the left side of the central figure, the fasting shield-bearer, is a line of Coup Sticks, on the right side, a line of Flintlock Rifles, together framing the stream of figures.

Coup Sticks recall the native way of warfare which gained warriors honor through the humiliation of an enemy. Plenty Coups said, "To count coup a warrior had to strike an armed and fighting enemy with his coup-stick […] or take his weapons while he was yet alive" (Linderman, Plenty Coup 55).

Firearms changed the method of warfare. Yet, for the Absaroke, the potency of firearms depended upon medicine, as we see in Hunts to Die's description of a war party:

Twice that night we stopped to make medicine, but not until almost morning was the great medicine-making begun; then the chief lighted a buffalo-chip and burned sweet-grass on it. The warriors sat at each side of him in a half-circle, while he sang a medicine-song and held his gun in the incense, and said, "I want you to strike the enemy in the head and thigh." All in turn we held our guns in the incense and struck them with our gun-rests, singing the chief's medicine-song in low tones, so that the guns would shoot straight. He told us not to bring bows and arrows to the incense. One man did so, and Red Bear said, "You must not bring these weapons here, for I saw only guns in my vision, and if bows and arrows are held in the incense, some one of us may be killed." (Hunts to Die qtd. in Curtis, vol. 4, 89)

Between the line of Coup Sticks (non-lethal) and the line of Flintlocks (lethal), the weeping figure carries the circle of his great shield. As modern observers, what indeed, we wonder, brings forth those tears?

Forces for Change and Continuance: Elk and Turtle

|

|

Apart from the panel, we find another image of Elk on the cave wall above it and Turtle on the wall below it. Elk, as we have seen, is connected to the force of love medicine, a force which leads to mating and growth, the young succeeding the old; as such, we can label it a force for change.

Water is a life giving. Turtle, a water creature, is associated with a very different kind of force. Lowie noted that "Early in the morning, winter or summer, the herald called out to the people […] `Make water come into contact with your body[…]. Water is our body. Whatever else there be, water is above all; without water you cannot live'" (Lowie, The Crow Indians 89). Water is in us. Water is what we need to continue living; as such, we can label it a force for continuance. Such a force had dangerous powers:

Before going into the water men and women painted red stripes about waist, wrists, and ankles, for protection against the water-monsters that were believed to inhabit all large streams. […] Necklaces of white beads were never worn in the water, for beads of that sort were believed to be hailstones, the symbol of the Thunderbird, a deadly enemy of water-monsters. (Curtis, vol. 4, 8)

A story called "The Offended Turtle" (Lowie, Myths and Traditions of the Crow Indians, 220-222) links the Turtle to the Water-monsters and to this force for continuance. In that story, a number of young men climb onto the back of a big turtle with large claws and are carried into a lake and drowned. To recover their bodies, the young men's relatives appeal to Thunder. There at the lake "Thunder was shooting all the time into the lake till dawn. Next dawn the woman bade her people look at the lake. It was dry. The water-coyote and the beaver-demon and other beings were all there. […] All the water-demons were there without any water. […] The same turtle that had captured them was in there" (222). The young man's relatives kill the turtle and recover the bones of their friends.

The opposition between these two forces, change and continuance, takes on mythic opposition in Crow storytelling. continuance and change, that is, permanence and development, becomes in myth the on-going battle between Thunderbird and the Waterpanther. All lives bear the marks of this conflict in some manner, for all of us attempt to establish some kind of stability yet must cope with change. Sometimes, too, we desire the change to end the limitations of stability. In the story called "The Thunderbirds" (Lowie, Myths and Traditions of the Crow Indians 144-146), we see the conflict of these two forces run amok, but Elk, the force of love, acts to restore harmony.

In the story, a young man is taken by Thunderbird to its nest. There, Thunderbird

tells him: "I have always had young ones, but just when they are getting along well something from the water comes up and devours them. […] I see the earth people and know that you kill anything and so I think you might help to save your sister and brother" (144).

The young man lays a trap. When two Waterpanthers make their attack, he kills them. Thunderbird rewards the young man with the power to become any bird he chooses. As a hawk, he goes on a murderous spree, killing the water animals he comes across: a beaver, an otter, a water-buffalo. Finally, he attacks Old Man Hidatsa, a big elk crossing the Yellowstone River:

[B]ut the elk was too cunning, caught him, and took him into the water, where there was a rumbling noise. The thunderbirds shot at the water, but could do nothing.

The elk announced, "I am bringing him, make a sweatlodge." He took him in. It was very hot. He switched him. Then he cried, "I'll stop it."

"Will you behave properly?" Then they stopped and took him out. "You are a person of the earth, you have already killed many water animals, don't do it any more. Your people are close by, go out, go home and become a human being again." (Lowie, Myths 146)

The young man abuses the power Thunderbird gave him by indiscriminately killing water beings. To recover the young man, Elk reconnects him to the element he has desperately tried to destroy: water. The Crow may divide the forces of life, but the story never divides them into exclusive forces: good and evil, benevolent and malevolent. The young man needs to regain respect for water-beings. The story puts humans between water and sky. The world operates through both forces, sky and water, continuance and change. The image of Elk and Turtle in Pictograph Caves may not be the mythic representations of those forces, but they can be seen, at least, as the benevolent animals associated with them, the gentle reminders that life involves us in the ceaseless negotiation between the demands of both forces.

Conclusion

The images in Pictograph Caves speak about the great forces in the lives of the Crow people, especially the visionary ones. Hope and quest, love and war, ecstasy and despair, loss and transformation, wounding and healing, life and death, continuance and change—these are the same forces in our own lives. Through the cautionary stories the Absaroke tell, these images begin to speak to us as well. Were we to relegate these images to mystery, think of how deaf we would become, but we can hear the stories of these figures. We can learn much from Absaroke culture, these images, what they may represent, and the stories they evoke. Perhaps it takes heart, the proper spirit, to really hear them. As one Shoshone storyteller said, "Sometimes these carvings talk at night. If you should look at the rock pictures, you would anger the Little People. To protect yourself from them, put on lots of paint, for the Little People are afraid of paint" (qtd. in Clark 197).

Works Cited

Brown, Joseph Eppes. Animals of the Soul. Rockport: Element, 1992.

Clark, Ella. Indian Legends from the Northern Rockies. Norman: Univer

sity of Oklahoma Press, 1966.

Curtis, Edward S. The North American Indian. Vol. 4. New York: Johnson Reprint Corporations, 1970.

Frey, Rodney. The World of the Crow Indians As Driftwood Lodges. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987.

Lame Deer. "The Vision Quest." In American Indian Myths and Legends. Edited by Richard Erdoes and Alfonso Ortiz. New York: Pantheon Books, 1984.

Linderman, Frank B. Red Mother. New York: John Day Co., 1932. Reprint, Pretty Shield, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1972.

—. "Morning Star—Son of the Sun." In Old Man Coyote. New York: John Day, 1931. Reprint, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996.

—. The Life Story of a Great Indian, Plenty-coups, Chief of the Crows. New York: John Day Co., 1930. Reprint, Plenty Coups, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1962.

Lowie, Robert. "Huàraáwic." Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, v. 25, pt. 1. New York: American Museum of Natural History, 1918. Reprint, Myths and Traditions of the Crow Indians, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993. 144-146.

—. "The Thunderbirds." Anthropological papers of the American Museum of Natural History, v. 25, pt. 1. New York: American Museum of Natural History, 1918. Reprint, Myths and Traditions of the Crow Indians, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993. 196-199.

—. Social Life of the Crow Indians. New York: Ames Press, 1912.

—. The Crow Indians. New York: Rinehard & Co., 1935.

Medicine Crow, Joseph. From the Heart of the Crow Country: The Crow Indians' Own Stories. New York: Orion Books, 1992.

Mulloy, William. A Preliminary Historical Outline for the Northwestern Plains. Laramie University of Wyoming Publications, 1958.

Nabokov, Peter. Two Leggings. Field manuscript by William Wildschut for the Museum of the American Indian. New York: Crowell, 1967. Reprint, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982.

Parks, Douglas. Myths and Traditions of the Arikara. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996.

White Bread. "Coyote Becomes A Buffalo." In Traditions of the Caddo. George Armstrong Dorsey. Washington: Judd & Detweiler, 1905.

Yellowtail, Thomas, and Michael Oren Fitzgerald. Yellowtail: Crow Medicine Man and Sun Dance Chief. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991.