Fall 2003, Volume 21.1

Fiction

Richard Dokey

Something Happened

Richard Dokey's new short story collection Pale Morning Dun will be published by U of Missouri Press (2004). The author of The Hollow Man, his stories have recently appeared in Witness, Beloit Fiction Journal and Noon. He is a previous contributor to Weber Studies. Read other fiction by Richard Dokey in Weber: Vol. 18.0 and Vol. 24.1.

The bridge was there. He sat on a dead stump to rest.

It was an old suspension bridge. The girders were rusty. The metal plates along the bridge, however, were shining hot where the vehicles had passed. The road went over the ravine and into the trees.

He climbed down the hill, his boots making little puddles of needles and stones that scurried ahead, and walked out across the bridge to look at the river below.

The river was shining too, a band of aluminum flame, interrupted here and there by grey, bubbling ash. It was much too far. Besides, it was three o'clock, the bad time of the day, and he knew that his brother, who always quit early, would be waiting. Carefully he placed the upper part of his body over the rail and spat. Then he went on back to the Jeep.

Frank was sitting on a folding canvas stool eating a peanut butter sandwich, a clear, plastic cup of milk in the other hand.

"So," Frank said, when he came up. "How did you do?"

"A couple of 18-inch brownies and six or eight rainbows under that," he said. "You?"

"A few," which is what Frank always said when he hadn't done too well.

He wanted always to fish with his brother, and they started out that way every time, but quite soon he would look up and Frank would be gone around a curve of the river or so far away that he could not shout to him over the tumbling water. It made him unhappy, but it was just as well. More than anything he loved fishing alone and listening to the high sound of the wind in the trees.

"Give me a sandwich," he said.

Frank opened the ice chest and drew out a plastic bag and a quart of milk.

"Don't drink out of the goddamned carton," Frank said, handing him a glass.

"Any more cigars?" he said.

"You brought plenty of cigars," Frank said.

He nodded and bit into the sandwich. The peanut butter was heavily smooth. He liked how it stuck to the roof of his mouth and how he had to make a clucking sound to get it loose or work it with his tongue, having the flavor go everywhere. He had liked peanut butter sandwiches from the beginning, when their father had taught them how to fish all that time ago. The old man was dead, though, and that was the name of that.

"So," Frank said. "What were you using?"

He put the carton to his lips, took a long swallow, bit into the sandwich. His mouth was thick with peanut butter. He enjoyed talking through it.

"Nymphs," he said.

"Nymphs," Frank said.

He nodded, watching his brother over the crust of the sandwich.

"What nymphs?" Frank said.

"Hare's ear," he replied.

"I was using hare's ear."

He nodded, smiling.

"What color?" Frank said.

"Dark," he said.

"Dark what?" Frank asked.

"Olive," he said, enjoying it. He had read four hundred books about flyfishing.

"I was using tan. Maybe that was it, then. What size?"

"Eighteen," he said.

Frank shook his head. "I had on a fourteen."

"The water's pretty low and clear now," he went on. "They spook easily. Then I was using those yarn indicators I tie up. They land softly. Better. You know?"

Frank used the hollowed out, fluorescent red balls clamped to the leader with a toothpick. They were easier to put on and to cast, but they splashed hard and looked like miniature barrels floating upon the surface of the river. Frank often was too lazy for his own good.

"There ought to be a caddis hatch this evening," he said. "We should get some good action."

Frank nodded, leaned back and closed his eyes.

The wind was in the tops of the pines. It moved an entire pine, stiffly, all the way down below the branches, so that the pine, moving, looked like one half of a great, wooden bow being pulled. Here, in the gully where they always parked the Jeep, there was no wind. It was warm in the sun. He ate, looking at his brother.

Frank was two years younger. His hair, greyer, was thinning at the crown, and he took naps in the afternoon. They had both gone to Berkeley, gotten their degrees, gotten married and divorced. Frank had three kids. He had two. The kids were scattered about. Frank had a woman now, for quite some time. He had one too. Neither of them had remarried. They never talked about remarrying. They just never got married again, and they were both over fifty, and it was too late anyway. They knew they never would remarry. It was the last thing their mother had spoken of, just before she died the season before, and they, the both of them, knew, without having to say a word to each other or to the old woman who had survived their father by twenty-five years, that they never should have married in the first place.

Frank was leaning back in the chair, his head against the door of the car. He thought about getting up and hiking down to fish the dark pools beneath the bridge, but it would be a tough climb getting there and tougher getting back. Then there was the hatch later when the sun would be behind the trees. He wanted to save himself. He had found that he could do everything as always, but it took longer to recover, and he had to save himself for what he really wanted to do. He couldn't do everything, but he could do what he really wanted, and what he saw in the mirror shaving each morning did not count.

He raised the lid of the ice chest and took out a Baby Ruth candy bar. Frank's mouth was open. It made a wheezy, wet sound. Frank would sleep now as long as he let him. He bit half way through the Baby Ruth. With the other hand he slammed down the lid of the ice chest.

Frank dropped forward, his eyes batting.

"I'll give you a few of those eighteens," he said. "I've got plenty tied up. We should fish nymphs before the hatch starts."

"All right," Frank said. "Sounds good."

"How about a cigar?" he asked.

"Why not?" Frank said.

He went around and opened the hatch of the Jeep. He had brought a handful of El Rey del Mundo from the humidor at home. He had a couple of hundred cigars cooking in the humidor. Bauza. Partagas. Padron. Aurora. El Rey del Mundo. He enjoyed acquiring knowledge of something and then using the knowledge. It didn't make any sense to go on with something and not know what you were doing. Frank smoked Chesterfield cigarettes and kept the few cigars he bought at the drugstore in a Tupperware bowl in the refrigerator.

He used a cutter to snip the ends of the cigars. He put one cigar into his mouth and handed the other to Frank. They sat in the shadow the pines made above the car smoking.

"You want one of my indicators?" he asked.

"I'll stick with the corkies," Frank said.

"I tied another nymph off the bend of the hook, by the way. Midge pupa. Increases the chances."

"I'll try it," Frank said. "How far?"

"Sixteen inches."

Frank nodded, closed his eyes and puffed the cigar.

He looked at his brother. They had slept in the same room as children. Now here they were grown men, old men, and being a boy with Frank seemed strange and impossible.

"I put flowers on Mom's grave Tuesday," he said.

Frank, who lived in the Bay Area, did not say anything for a time. Then he said, "That's fine."

"They're keeping it up pretty nice," he said. "The grass and the leaves, I mean. They keep it clean."

A breath of smoke drifted above Frank's hat. Frank rolled the cigar in his mouth. "Fine," he said.

The old man's grave was on the other side of the cemetery, and he never visited it. He didn't know what Frank did. He didn't know if, after dropping him by his own place at the conclusion of a fishing trip, Frank ever stopped at the cemetery. It was a small thing anyway and didn't matter. He was sure that, after a time, he would not go regularly to their mother's grave. It was one of those things at first, which, after awhile, you just let go of. It was probably a good thing to let go.

"You want your Baby Ruth?" he asked. "I already had mine."

Frank dropped forward and pulled the cigar from his mouth. "I expect I'd better," he said, "or it won't be there later."

"We still have those cookies Alison made," he grinned. "Too many of those for me to wolf down. You'll get your share."

Frank peeled back the wrapper of the candy bar and took a small, tentative bite.

"I don't see how you do that," he said. "I can't do it in less than two bites."

"That's easy," Frank said. "You're a hog."

"Hey," he said, "remember how, when we were kids, we'd put a whole loaf of that white bread away between us for dinner and a half gallon of milk. And still go out and play."

"I haven't got that appetite anymore," Frank said.

"Well, hell, I don't eat that way either, but I sure haven't lost the taste for it." He opened the ice chest and removed one of the cookies Alison had baked.

Frank stopped eating the Baby Ruth. The cigar went out.

He wondered, did Frank ever remember the silence of so many of those dinners so long ago? Their father had begun the affair when they were kids, and it had continued right on through their school years, including college, and even after they both had been married and had started families. He was the older and had seen what was happening and took his mother's side. Frank got what was left. It had not been planned. He just couldn't help it. He couldn't help hearing his mother cry or watching her face or seeing how she was. He couldn't help being afraid that she could leave and never come back. He didn't know if Frank was afraid too.

Now they were as old as their father had been when he died of the heart attack in that other woman's place twenty-five years before.

"Say, Frank," he said, "remember our trip to the Bighorn last August, just before Mom went?"

"What of it?" Frank said.

"We sure knocked them, didn't we?"

"It was a good trip," Frank said, relighting the cigar.

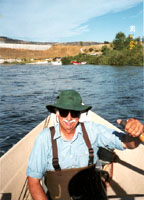

"Remember, we floated down to that little island just below the put-in and they were rising right up along the bank, and how Hale came by rowing those two fat guys from New York and kidded me about no fish being in there, it was too close, and then I nailed a big one right as the boat went by and they applauded, like it was a movie?"

"You and that competitive thing," Frank said.

He straightened, staring at his brother.

"What does that mean?" he said. "It was great, wasn't it? It was a real occasion."

"You want the rest of this Baby Ruth?" Frank replied, taking his rod down to retie the leader.

Later the sun was behind the trees. They stood on the flat ground above the bridge looking at the river. They did not fish the river below the bridge, where the light was low and the coming back dark and arduous. They always fished here. The walking was easy, the riffles and runs, moderate and soft.

"A pupa," he said. "Right along the bottom. Until we see some surface action."

"And another tied off the bend. Sixteen inches."

"Right," he said.

Frank smiled.

They fished that way for a time, waiting for the hatch, waiting as they always had. The sun went lower still. Then the caddis appeared, bobbing and ducking above the water. They entered the river. The rods began working, the pale lines sailing out, the tiny imitations drifting to the surface, where the trout took them savagely. The light faded, and though the fishing was good, as good as it ever was, a heaviness entered his heart. He left the water and sat down upon a large rock.

Something happened all those years ago, something terrible and lonely making, when, finally, he told his father that time at the dinner table just what he thought about it, and his father went outside and his brother went with him. They had come up through that time and never talked about it. All the years and all the separation, and they came together only to fish, speaking about nothing but the rise of trout and the mystery of the one that got away.

He looked up.

Frank was gone around a bend in the river.