Spring 1999, Volume 16.3

Essay

Joan D. Stamm

Refuge-Refugee

Joan Stamm has an M.F.A. in writing and literature from Bennington College and is the author of If I Touched An Eagle and numerous articles. Her volunteer assignment led to full-time work with refugees and a deeper commitment to the precept of "service" as practiced in Zen Buddhism.

"There is no greater sorrow on earth than the loss of one's native land."

—Euripedes, 431 B.C.

The rain patters on the roof of my truck, makes the freeway slippery, a shiny black ribbon dotted with glowing brake-lights. It is rush-hour and visibility is blurred by the downpour, by the road spray; it is not a night I want to be out, but I have volunteered to teach English to refugees for six months and tonight I must watch others, learn techniques, take notes, all part of my training. I have only a vague idea why I'm doing this: something about being of service, about "compassion in action" advocated by Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese Buddhist monk and hero of many nationalities, a refugee exiled in France. Nhat Hanh's own service to the displaced was dramatized in 1976 when he hired four ships out of Singapore and rescued over eight hundred "boat people," Vietnamese citizens who otherwise would have perished in the Sea of Siam. The project was named, "When blood is shed, we all suffer." My own compassion in action will not be anything this sensational, nor will it require traveling more than the seventeen miles from my house. But I will still need the mantras of "service" and "action" to keep me inspired on this rainy night, a night I'd rather be reading a travel book in front of my fireplace.

I cross the floating bridge—it is hard to distinguish the blacktop from the lake-top—exit the freeway and head for Martin Luther King, Jr. Way, a street that runs through a Seattle neighborhood known for drive-by shootings at bus stops. Six blocks from my destination some mysterious hand sets a scene in motion that tests my commitment and increases my growing trepidation: the car in front of me suddenly comes to a halt at a bus stop, the door flies open, and a teenager jumps out. He leaves the door wide open and the engine running while he runs over to a group of young men standing on the sidewalk. A dozen cars, their headlights gleaming in my rear-view mirror, jam up behind me. Nobody honks—honking triggers "road rage" these days, gets you shot at close range. I wait and watch, listen to the steady squeak of my worn windshield wipers scraping back and forth across the glass, anticipate some kind of gang affair to unfold on the sidewalk. I have to drive this same route for the next twenty-four weeks and the potential ramifications begin to corrode my impulse to serve. Perhaps I've made a mistake.

Still, amid the fear of unknowing, the doubt, I recite my mantras and recall the film in my training class, the one about a Hmong family's strange and frightening journey to America. I remember a tangible reason for having signed up: the family of six who fled their mountainous homeland from a war they didn't start—like most of the fifteen million refugees worldwide. The Hmong family became travelers in the night without a suitcase, without a return ticket home, and ended the first leg of their journey at a refugee camp—a row of asbestos shacks—where a small bag of rice, a pail of water, a plastic tarp and a new set of clothes were issued. Every day they waited for food, water, work, news, sponsorship, for their grief to go away. Then one day someone in Seattle, Washington, invited them to come to America.

Still dressed in traditional clothes, the women in heavily embroidered skirts and jackets, the men in baggy pants and colorful sashes, both sexes wearing black turbans or caps, the Hmong family boarded a bus for the airport. They hung their heads and hands out the window, touched loved ones they might never see again and sobbed as the bus pulled away. None of the family members had been on a plane before, or anywhere outside their village and the camp. On the seventeen hour trip to Seattle, they learned about food in plastic wrappers, knives and forks, flush toilets, emergency exits, and the safety features of a Boeing 747. At U.S. Customs and Immigration they were issued social security numbers and an I-94 card that listed their vital statistics. The customs people pinned these cards to their lapels—even the adults—as if the Hmong were children who might get lost in the crowd.

Whisked away by a friendly foreign face on the other side of customs, the Hmong family ended up in an apartment in the inner-city, a place not far from this bus stop. Sirens and car alarms and alien gadgets like the dishwasher, shower, thermostat and fireplace, frightened and perplexed them. They would learn the hard way that air ducts were not water drains, that fireplaces had flues, that dead-bolts should be locked, and that swarms of cockroaches crawling around their kitchen need not be tolerated in Seattle. The rain continues to beat on the hood of my truck, the wipers ticking back and forth like a metronome. The teenager hands something to his friends—drugs, a gun, a pack of chewing gum? He jumps back into his car, releasing me and the chain of cars trapped behind me from the stress of uncertainty.

Stress. Uncertainty. I speed off into the night, remembering more of my training, the stuff about thieves in the camps, wild dogs, rapists. The guilt of having survived. Many refugees lose a loved one along the journey: a child or spouse, mother or father, and they, the survivors, spend sleepless nights under asbestos roofs wondering why they still live.

My destination, the Refugee Women's Alliance, or ReWA, is around the corner. I careen into the crowded parking lot and wedge my pick-up between a mud hole and the garbage dumpsters. Under cover of an umbrella, I run toward the gray, flat-roofed building, a remnant of the federal housing projects. The paint around the steel-barred windows peels in shades of brown. The entrance, a makeshift plywood ramp and stairs, unpainted, looks like an after-thought. I bound into the building checking my watch.

Once inside, my first impression is that of bright colors, although on second glance the walls are a dirty beige and the carpet a frayed brown. The feeling is bright, I reason, then notice a bouquet of candy-pink satin flowers on the front desk, a red and green striped couch by the door and embroidered sashes, appliquéd aprons, woven shawls, braided tassels and primary-colored pompons on pearl-beaded strings hanging in glass cases. Photographs of smiling faces from every race and nationality are pinned to bulletin boards. World maps and posters of African basketry, Buddhas and ancient Cambodian temples are taped to the walls.

ReWA feels like an oasis, a safe haven for newcomers. I will learn that it serves men and women of all nationalities, provides day care, domestic abuse counseling, citizenship training and English classes. It was established in 1984 by Emmanuelle Chi Dang and a group of resettled Southeast Asian refugee women who were not being served by existing services, services then and now that include eight months of government sponsored ESL classes that are supposed to mold refugees into productive members of society, that are supposed to prepare them—even those who were illiterate in their own language—to fit in and find work. And these days, finding work, a JOB, is critical in the new political climate that abhors welfare and anyone who depends on it.

I head for the classroom, pass a nursery where children's voices, light and merry, filter out, and enter a room with twenty students, five volunteers, four observers and a teacher. The air smells like a combination of damp sweat and exotic oils.

I slink into a seat in the back, my dripping umbrella at my side, and search for a pen in my purse. When I look up I see a large coffee-colored Somali woman observing hijab, the Muslim custom of covering the head and body in accordance with the Qur'an. Her outfit is a striking combination of two shades of yellow—lemon and canary—a brilliant contrast to the all black robes of Iranian Muslim women.

The woman in yellow exudes an aura of complete self-assurance as she strides across the room and takes a seat. I begin to study her. Her hair, a mound on the top of her head in the shape of a miniature hay bale, stays hidden under yards of yellow cloth, a covering so thoroughly pinned in place that not one stray wisp trails out. Her hands, the only other flesh exposed, flash fuchsia nail polish, slightly chipped. A floor-length print skirt of tropical flowers hangs below a second layer of yellow. With her wide dark face and dark eyes framed in bright yellow, she looks like a hybrid sunflower, a grand beam of African sunlight.

The woman sitting next to her is a different kind of hybrid, less brilliant but grand nonetheless. She wears a similar style garment around her head and shoulders, but in green and black squiggle stripes. Under the stripes she has donned two layers of contrasting prints: a rust-brown geometric and a deep purple floral. None of her prints, stripes, flowers, or color combinations match or compliment each other in any standard Western sense of dressing, and the disparity between her attire and the Americans in the room—all wearing versions of Northwest drab: variations on navy and neutrals—symbolizes our other cultural differences: race, religion, language, nationality. Will these women shed their ethnic finery someday?…replacing the yellow head covering with nondescript beige or brown, the stripes and prints with solids? Will our clothing colors then be our one commonality?…submission to uniformity, collusion with the gloomy climate.

The American volunteer helping the two Somali women is yet another hybrid. She stands about five-feet ten-inches—a real bean-pole of a twenties-something blond—and sports tight black lycra bell-bottoms and a white, V-neck T-shirt one size too small. Her ample breasts, which bubble up out of a black under-wire bra every time she leans over, tops off, so to speak, her ensemble. The young woman's appearance seems to be saying, Welcome to America; here, anything goes. What do the Somali women think of this woman's open sexuality? Are they offended? Accepting? What's noticeable is how, in some ways, the Somalis dress wilder and freer than Americans do, unhindered by limitations of color and design. Yet the biggest revelation is how sharply the three women's distinctive clothing marks the complexity contained in this room, this experience and what I might learn—surely more than how to teach English. I suddenly feel the anxiety of deficiency. What do I know about Somali culture? Or about the Muslim religion? Or about civil wars between African nomadic tribes? I need to read articles, books, encyclopedias. But how can I know about them all, about the other nationalities—Thai, Cambodians, Eritreans, Oromo, Ethiopians, Lao, Hmong, Vietnamese—in this one crowded classroom? Every student has a distinct culture, mysterious background, a story to tell. I want to respect and dignify their lives and experiences, but I'm keenly aware of my ignorance, and I fear stepping on culturally different toes. And diversity training, though well intended, has only reminded me of what I know but often forget: be wary of personal space, touching, eye contact.

Have I been staring? Should I look away? Just as these newcomers are learning how to be American, I am learning how to bridge the gap and be a useful guide. The way does not seem clear.

I try to concentrate on taking notes, to see the patterns behind the teacher's methods so that I can duplicate them, but I'm distracted by the array of nationalities in the room and grow ever curious. I Melissa Hollister would like to sit down with each person and, over a cup of coffee and a sweet have a long talk about their country and customs in a language we both spoke fluently even though I know this can't happen. These students are just beginning to learn my language and none of the languages I've studied would get me far in any conversation. I feel cheated and disappointed. I might never know the people in this room, or get to speak to the Somali women about their lives. Before me sits the whole world, every corner of the globe represented, with no satisfactory way of reaching into the finer nuances of our common or uncommon existences except to smile and look welcoming and learn as much as I can about how to teach my language.

As the night progresses, emotional distance becomes increasingly difficult as I observe an intermediate class with higher level English skills. They can express key bits of information: snippets of lives and deaths. Stories, parts of them at least, begin to emerge into the brightness of this fluorescently lit classroom, this shabby building in an affluent land where all these brave and unsuspecting people have come to find refuge. The teacher, a fair-skinned woman in her thirties, with a faint British accent and long brown hair twisted and knotted like a skein of yarn, gives a lesson on "the family." She holds up a picture of her family, reviews the words, then writes "mother," "father," "brother," "sister," "daughter," "son," "husband," and "wife" on the board. She reinforces the words by drawing stick figures, then produces real sticks from a set of Cuisinaire rods. The tall black rod represents the teacher's husband, the shorter brown rod represents her, and the green, pink, yellow and blue rods stand for her brother, sister-in-law and parents. The students are supposed to depict their own families and explain the configurations to their neighbors.

As the students receive their portion of rods, some of them snicker, others look shy or terrified, and still others begin to build extended communities with their pile of colored sticks. A Vietnamese woman about forty, with a zigzaggy scar that runs from the base of her chin to the top of her collarbone, touches two short black rods, giggles, and says, "This my son and this my daughter… But they dead now." I look up from my notebook. Had her children died of disease? Typhus perhaps? Dysentery? Had they stepped on a mine? Been shot? Fallen out of the boat? She is talking to no one in particular, but still smiling, she looks over at me as if to check my reaction. I smile back, a feeble gesture meant to convey empathy. She looks satisfied for the time being, goes back to her rods, rearranges them, and waits to hear about her neighbor's family.

The Cambodian man across from her, about fifty, wearing Western style clothes, doesn't seem to be listening to her or anybody. He struggles with his own family configuration, a group of seven sticks laid out on top of a three-inch thick, leather-bound, gold-embossed English-Khmer Dictionary encased in clear plastic. Khmer has the most letters of any alphabet—seventy two; it was the language used by Pol Pot to carry out a ruthless reign of genocide. I don't know this man's personal history, but I know about the Cambodian holocaust of the 1970s. Where has this man been all these years? The Thai refugee camps, where many Cambodians fled and where some lived for nearly twenty years, are closed now. Some of the refugees in those camps were Khmer Rouge soldiers, men who had slaughtered their own countrymen and escaped the Vietnamese invasion. Was this man a Khmer soldier? The thought took me by surprise, frightened me. In the late '70s, I worked with the American Friends Service Committee on an educational campaign, informing interested groups about the tyranny and brutality of the Khmer Rouge uprising and the hundreds of thousands of educated and intellectual Kampucheans who were murdered and starved to death at the hands of Pol Pot's forces. The Khmer Rouge were a diabolical force, as evil in my mind as the Nazis; their actions just as heinous. Now, twenty years later, I could be sitting next to one, even though the possibility is all supposition since the U.S. government was supposed to screen out Khmer Rouge soldiers from obtaining visas. Just as quickly I realize how impossible this task would be, how easy it would be for someone escaping retaliation to manufacture stories, papers, important documents, in a country with a collapsed government, invading forces and inadequate currency.

Compassion. Action. Whether Khmer Rouge or not, innocent or guilty, I tap the top of his dictionary, smile and say, "A lot of words in there." He mumbles something and looks away as if to say, You have no idea. And of course I don't. I know as little about his language and culture as I do the Somali or the Hmong or anybody else in this room. Oh, I know a little history, a little geography, some of the nightly news events, but what do I know about childhood games, or places they loved back home—a mountain walk, river bank, ocean beach. And what does he know about me and other Americans that isn't some kind of stilted stereotype, a media image, or slogan, exported to sell something that most people, Cambodian or American, don't need?…like the first Japanese McDonald's in Tokyo that advertised, "If you keep eating hamburgers, you will become blond!" I didn't want to cram my culture down his throat in a way that would force him to exclude his own.

For part two of the "family" lesson, the teacher holds up a printed page that has three pictures and a monologue. An American woman named Rose, who has two daughters, says she is unhappy because her husband Jim had a habit of not coming home. Now she is divorced and has to raise two girls by herself—some curriculum developer's idea of the All-American family? But what will this lesson teach? That American men are irresponsible? That American women are victims who must survive on their own? I try to gauge the appropriateness of my criticism. It is only one night's lesson, one scenario in a series on types of families.

The teacher asks, "Why do you think Jim didn't come home?" A Thai man with six children offers that Jim was probably drinking and playing cards, and that he'd lost all the family money. "No money, no honey," he says, and everyone laughs.

The teacher then tells her students that she has been married for five years but doesn't have any children. One woman, a Muslim, who struggles to keep her hot-pink head scarf tight around her face, says that she's been married five years too and has only produced one child. She is worried that her husband might divorce her or take another wife. Another woman murmurs that she has too many children. Another shakes her head and says that she married too young, only fifteen when she had her son. None of the women seem to comprehend how their teacher could be married for five years and not have any children at all. What would they would think of me: a forty-four-year-old woman with no children and no husband either? Did I have any importance in their culture? Any place in society? In India I could be burned alive for being so worthless. In Bangladesh or Pakistan or Saudi Arabia, I might be considered a prostitute, buried in a pit up to my neck and stoned to death. But since I am American, maybe my lifestyle seems like a positive option, something to ponder, tell their daughters about. Somehow I doubt it. Motherhood is still seen as the pinnacle of womanhood by most cultures, including my own. I suspect it is a deep-seated notion encoded into our genes, or at least into our upbringing. I am an aberration, an anomaly, but I hope my oddity will not bar me from these women's worlds. I know I won't bar them from mine.

Motherhood. Marital status. More symbolic indicators in this puzzle of cultural differences, this maze of potential misunderstanding. I will learn later that the first question all refugee women will ask me is either, Do you have children? or, How many children do you have? And that when I indicate zero with my thumb and forefinger, that they will not understand the complexity of my answer, that not having children was a choice I made without regret, and not a reason to feel tormented or worthless or less of a woman.

At 8:00 the teacher calls it a night. "Don't forget to practice at home," she reminds them. The students are quiet, ponderous. They shuffle into the hall carrying books and folded hand-outs. I close my notebook and watch them go before I too run out into the night the same way I came in: under cover of an umbrella. Some of the students, including the Somali women, are standing on the steps in the rain waiting for rides. The Vietnamese woman with the scar is met by a girl about eight years old. A new daughter? One that lived? They take each other's hand and head across the parking lot.

I want to offer my umbrella to the woman and her daughter, to the Somali women, to all the refugees standing in the rain. I know that many of these students had to flee their homes in the middle of the night, or at dawn, or whenever they could sneak out of their hiding place without being shot. Some trekked over mountains, others through mine fields, many hiked down long dusty roads. A few ran through the tangle of jungles with tigers tracking their scent, and others piled into over-crowded leaking boats and set out into rough waters. The lucky ones made it to some distant soft-sand beach or were rescued at sea by friendly sympathizers; the unlucky ones disappeared in the trough of a wave.

I want to shield these newcomers from all discomfort, all suffering, even the harmless patter of this temperate rain. I want to protect them while they take those first uneasy steps in my country. But then I notice that many of the students have umbrellas, that the Somali women, undaunted, have conveniently pulled their head coverings a little tighter to keep the relentless drizzle off their hair, that the woman and child have flipped the hoods up on their warm parkas. Everyone is coping, surviving; it's just rain after all, not a typhoon or a flood or a storm in the South China Sea.

As I wait for the cars in front of me to exit the parking lot, I watch the students in their various costumes maneuvering in the rain, the same rain that runs off their umbrellas and gushes in streams down sidewalks and into gutters, rain that raps on the roof of my truck in a soft steady prickle. I peer out my wet windshield like a submarine pilot who's surfaced in some foreign port, a place or land not known before—or perhaps I had known it but then forgot, or wanted to forget, wanted to remain incognizant of the quiet pain of the newcomers, the refugees who arrive in my city every day battered and scared. Where is their welcome mat? Their apple pie? Why have I been such a poor neighbor?

Before I re-submerge, the woman and child walk through the beam of my headlights and look up at me from under their parka-hoods. I look back from the protection of my cab and smile, wave. Their return smile, return wave—bigger than mine, eager and welcoming—reminds me of the age-old wisdom: service to others, compassion and giving, often comes back in unexpected ways. It is a little thing, a smile, a common gesture of friendship. But I am humbled nonetheless. I think about the woman and child all the way home, and even now, as if I'm looking through a periscope, I see their radiant eyes, almost gleeful, beaming through their private heartache, breaking down our common travail.

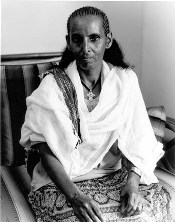

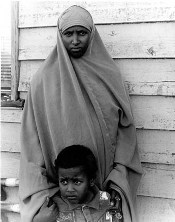

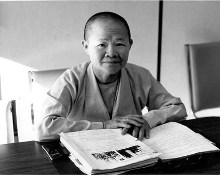

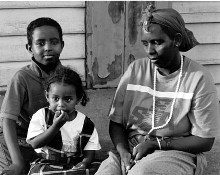

Refugee Women

[Click on pictures to enlarge]

Photographer Melissa Hollister was raised in Reno, Nevada, and moved to Seattle in 1996. She graduated from the Art Institute of Seattle in 1998 and is currently doing free-lance photography work.