Fall 1994, Volume 11.3

Essay

Stephen Trimble

A Wilderness Photographer in Marlboro Country

Stephen Trimble writes about and photographs western wild places and native people. His most recent books are The People: Indians of the American Southwest (School of American Research Press, Santa Fe, 1993) and The Geography of Childhood: Why Children Need Wild Places (Beacon Press, 1994). He is working on a novel set in southern Utah in 1950. Read other work by Stephen Trimble published in Weber Studies: Vol. 19.3 (art), Vol. 19.3 (conversation).

[Click on picture to enlarge.]

I.

On a serene afternoon in August, 1985, I left Santa Fe for the half-hour drive to my little adobe house in New Mexico's Pojoaque Valley. The highway bears north between the trench of the Rio Grande and the high spine of the Sangre de Cristo Range. Summer clouds were building over the mountains, piling into the most spectacular thunderheads I had ever seen. I gunned my truck, racing for home and cameras.

On a small hill behind my house, I shot two rolls, photographing as the clouds rolled over the peaks. I photographed until the last flicker died within the storm clouds—ominous mushrooms fired by golden and red light. I was thrilled to have seen this event, and exhilarated to have the chance to photograph it.

The storm itself was not unusual. In July and August, warm air, high altitude, and Gulf moisture create what Southwesterners call the monsoons—afternoon thunderstorms that build, roil, rain, and disappear over several hours. By sunset, the sky clears, washed clean, and ready for a glitter of stars.

But these clouds were especially remarkable in their form. They towered over the Pecos Wilderness, while the sky above me was a radiant blue. The sun at my back lit the tableau; color and form changed with each interval closer to sunset. The drama climaxed right over Truchas Peak, a cardinal sacred mountain for Tewa Pueblo people.

II.

October, 1989: my daughter was a few months past her first birthday. She had had a restless night in a cabin outside of Torrey, Utah. My friend, Chuck Smith, woke up early and wandered out into the piñon-juniper woodland for a morning pee. His wife and my family stayed snug inside. I was too groggy to be up at dawn for photographs.

Chuck returned and called me awake. "Steve, you have to go outside and see the cliffs. Terrific light..."

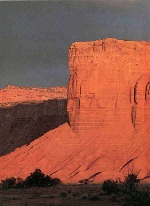

I roused myself, grabbed my tripod and cameras, and hurried outside. The sun had risen into a narrow opening eastward beyond the Henry Mountains. Silver storm clouds filled much of the rest of the sky arching over the Waterpocket Fold. Orange light shot across under the cloud cover, firing the Moenkopi sandstone cliffs under the dark ceiling of the storm. I knew the intensity of color would last only a few minutes. I gritted my teeth against my own full bladder and photographed as fast as I could, changing lenses, trying a polarizing filter to intensify the contrast between cliff and sky, quickly shooting a series of pictures.

And then the light was gone. I went back inside and curled into the warm hollow of my wife's back and drifted once more into sleep.

III.

What do you say when the phone rings, and Exxon wants to use your photographs of pristine nature in an ad promoting their corporate sensitivity to the environment? I would say no. What do you say when Philip Morris offers you big bucks to use your photos to sell Marlboro cigarettes? I said yes.

The Chicago advertising agency representing Philip Morris called me after they saw a book of photographs of the Colorado Plateau that I had edited called Blessed By Light. They wanted, first, a big red cliff, and, later, a thunderhead. They wanted my photographs for Marlboro adsbut needed computers to add cowboys and horses to the foregrounds of each. "Now there's a special place in Marlboro Country." "Come to Marlboro Country."

I have told you the stories of these images. I saw no cowboys or horses in Marlboro Country; no one smoked cigarettes there. Although there was a woodstove and a cold beer not far away, wilderness began at the doorstep. Philip Morris, of course, used these pictures and what they communicate about wilderness for corporate purposes, for mythmaking, profit, and the despicable enticement of people to cigarettes.

I am a professional photographer, and so I was delighted to see my photos used so conspicuously, to be paid so well for their use. I was unsettled, too. I do not smoke, and do not like anything about smoking. I hope my children never start. But I also know that the Marlboro image is powerful and unchanging and that my particular images will not target any new audience, will not convince any one person to begin smoking.

And then there is the issue of using the wilderness. Politically correct critics suggest that even conservation-oriented photo books of pristine wilderness are at best boring or nostalgic, at worst destructive. Conservationists worry that more books of "perfect" and beautiful landscape photography will make the public complacent. Some call such photographs pornographic, a perverse misrepresentation of the wilderness as a Playboy centerfold, an unreal beauty without flaws or complications.

I can only imagine what such commentators think of using wilderness images for advertising cigarettes.

I thought through the conflict in values. My solution has been to allow the use of the photos but to send some of my profits back to where they originated, back to the wilderness.

And so I tithe. A portion of each Moenkopi cliff check goes to the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, to fight the dam proposed below the base of the very cliff in the photograph. A percentage of the payment for the thunderhead over sacred Truchas Peak goes to the Native American Rights Fund, to lobby for passage of the Native American Religious Freedom Act, to fight for the protection of sacred places.

The wilderness gives itself to photographers. We have an obligation to think about what we take. And what we give in return. Our exchange resembles that of a native hunter who thanks the spirit of a deer he has slain for its gift of life and who then leaves behind a piece of meat for Mother Earth. With these kinds of agreements with the wilderness, with this kind of attention paid, the lessons of the experience can be understood. In this way, the wilderness may continue to survive, as our refuge and teacher, and, yes, as our place of work, as well.