The Modern Accident

(1) MP William Huskisson, the "first" railroad fatality

Opening day of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, 15 Sept 1830

The engine had stopped to take a supply of water, and several of the gentlemen in the directors' carriage had jumped out to look about them. Lord Wilton, Count Batthyany, Count Matuscenitz and Mr. Huskisson among the rest were standing talking in the middle of the road, when an engine on the other line, which was parading up and down merely to show its speed, was seen coming down upon them like lightening. The most active of those in peril sprang back into their seats; Lord Wilton saved his life only by rushing behind the Duke's carriage, and Count Matuscenitz had but just leaped into it, with the engine all but touching his heels as he did so; while poor Mr. Huskisson, less active from the effects of age and ill-health, bewildered, too, by the frantic cries of "Stop the engine! Clear the track!" that resounded on all sides, completely lost his head, looked helplessly to the right and left, and was instantaneously prostrated by the fatal machine, which dashed down like a thunderbolt upon him, and passed over his leg, smashing and mangling it in the most horrible way.

– eye-witness Lady Wilton, who told Fanny Kemble about the accident, 1830

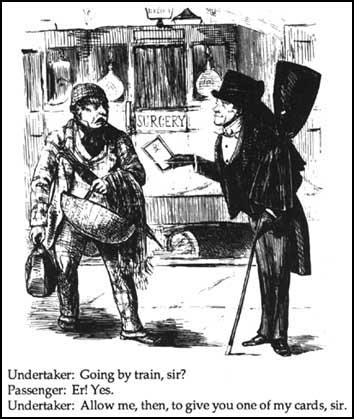

(2) John Leech, Railway Undertaking, Punch Magazine (1852)

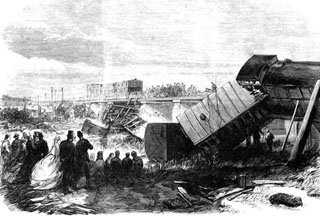

(3) Charles Dickens and Staplehurst: Railroad Trauma (1865)

I was in the only carriage which did not go over into the stream. Our carriage was caught upon the turn of some of the ruin of the bridge and hung suspended and balanced in an apparently impossible manner. I got out with great caution and stood upon the step. Looking down I saw the bridge had gone, and nothing below me but the line of rail. Some people in the two other compartments were madly trying to plunge out of the window, and had no idea that there was an open swampy field fifteen feet below them and nothing else. Suddenly I came upon a staggering man covered with blood (I think he must have been flung clean out of his carriage), with such a frightful cut across his skull that I couldn't bear to look at him. I poured some water over his face and gave him some brandy, and laid him down on the grass, and he said, "I am gone", and died afterwards.I don't want to be examined at the inquest and I don't want to write about it. I could do no good either way, and I could only seem to speak about it to myself . . . . I am keeping very quiet here. I have a - I don't know what to call it - constitutional (I suppose) presence of mind, and was not in the least fluttered at the time. I instantly remembered that I had the MS of a number with me and clambered back into the carriage for it. But in writing these scanty words of recollection I feel the shake and I am obliged to stop.

– Charles Dickens, June 1865 (emphasis added)

On Friday the ninth of June in the present year, Mr & Mrs Boffin . . . were on the South Eastern Railway with me, in a terribly destructive accident. When I had done what I could to help others, I climbed back into my carriage - nearly turned over a viaduct, and caught aslant upon a turn - to extricate the couple. They were much soiled, but otherwise unhurt . . . I remember with devout thankfulness that I can never be much nearer parting company with my readers than I was then, until there shall be written against my life the two words with which I have today closed this book - The End.

– Charles Dickens, postscript to Our Mutual Friend,

which he had been reading through when the accident occurred

The accident at Staplehurst on the South Eastern Railway is remembered chiefly for the survival of the train's most eminent passenger, Charles Dickens. At the time of the derailment, he was reading the manuscript of Our Mutual Friend while on his way back to London after a visit to France. The accident should have been avoided, despite the absence of two sections of rail, if various safety procedures had been carried out. A labourer should have protected the line by placing a detonator every 250yd from the viaduct for l,000yd at which point he should have placed two more 10 yd apart and remained there with a red flag. The foreman, however, had placed him only 554yd away, and since there were only two detonators to hand, the foreman instructed that they were only to be used in the event of jog; it was a sunny afternoon. The shortened distance made it impossible for the driver to stop after he had seen the red flag, and the guard failed to realise the urgency on hearing the brake whistle, applying only the screw brake and not Cremar's patent brakes with which the leading van and two coaches were fitted. Dickens was unhurt and went round the victims administering what he thought was a helpful restorative - brandy. Some of them died immediately, which puzzled Dickens, occasioning him to note that 'Mr Dickenson was the first person the brandy saved'. There is no doubt that Dickens' nervous system never recovered from the accident. One of his companions on the protracted reading tours recorded that Dickens would writhe with nervousness whenever an express gathered speed. On the fifth anniversary of the accident, 9 June 1870, Dickens died in his fifty-eighth year. Whatever else, a platelayer's error deprived us of a solution to The Mystery of Edwin Drood. (my emphasis)

– The Illustrated London News, 17 June 1865

Suddenly, somehow, and somewhere. . . and obstruction is encountered, a jar, as it were, is felt, and instantly, with time for hardly an ejaculation or a thought, a multitude of human being are hurled into eternity.

– Charles Francis Adams, Notes on Railroad Accidents (1879)

(4) for 40 years, crashing trains was one of america’s favorite pastimes: from 1896 until the 1930s, showmen would travel the country staging wrecks at state fairs.

ON SEPTEMBER 15, 1896, TWO locomotives crashed head on 14 miles north of Waco, Texas. The locomotives’ boilers exploded on impact, sending debris flying through the air for hundreds of yards, killing at least two spectators and maiming countless others. One man even lost an eye to a flying bolt.

But no one ran from the calamity. In fact, after the crash, thousands of bystanders ran toward the destroyed locomotives hoping to claim a piece of the wreckage. That’s because the 40,000 or so people scattered along the tracks that September day knew the locomotives were going to crash and had paid to be there.

From 1896 until the 1930s, staged train wrecks were a popular—albeit destructive—event at fairs and festivals across the U.S., long before anyone ever thought of wrecking old automobiles at a demolition derby or monster truck rally. To read more, click here, or here: Crash at Crush